In Muriel Villanueva’s poetic, undulating The Left Parenthesis, a young mother works towards repair and reinvention, threading together the disparate reflections of selfhood. Under the guise of notes on reprieve, Villaneuva delves into surreal ascriptions of consciousness, of a psychological journey that braids together experience and fantasy. In beautiful, spare language, The Left Parenthesis is an open punctuation, seeking outwards to define that which is in constant flux—life.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

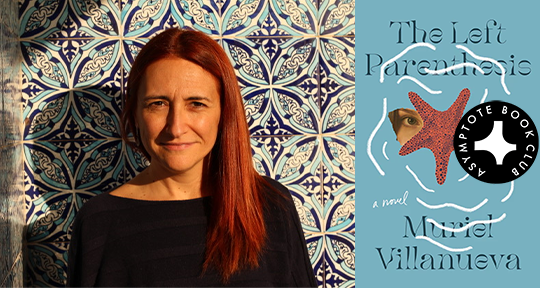

The Left Parenthesis by Muriel Villanueva, translated from the Catalan by María Cristina Hall and Megan Berkobien, Open Letter, 2022

I knew you weren’t well, but I pretended it wasn’t true, because the whole thing made me sick, too. If you died, so did I. If we were a pair, what would that make me afterward?

What do you do when you define yourself by your relationship to another person, and that person ceases to exist? How do you go about allowing the self that you have become to crumble away, making room for a new self to grow? Muriel Villanueva’s The Left Parenthesis—a slim, surreal novella tracking a woman’s trip with her young baby to a small beach town—examines precisely such questions in sparing, direct prose.

The narrative follows the inner life of a woman seeking to understand herself. Throughout the novella, the protagonist, also named Muriel, unpacks and dissects her three selves: the self that is a mother to her daughter Mar, her wife-self (she tells us at the start that she is a widow), and the self that acts as a mother to her own husband. She grapples with the fact that she was never sure which of her selves would emerge when she opened her mouth, a response to her husband’s oscillation between his child-self (the one she felt compelled to mother) and his burgeoning man-self. This three-week excursion, a brief parenthetical phrase within the novel that is her life, is something she undertakes to hopefully catalyse a transformation within her, a process of purging and healing.

Threaded through this book is the eponymous theme of an opening parenthesis, an explanatory and exploratory phase of existence that is separate—parallel—to the day-to-day. “At the beginning of my stay here I thought the cove with the shape of a waning moon. Now I think it’s only a parenthesis. It opens over here and I don’t know where it closes.” The cove to which the protagonist retreats is curved like a parenthesis, simultaneously opening out and welcoming in. This symbolic shape is mirrored in the curve of her arm as she breastfeeds her infant daughter, nurturing her baby as she herself is being nurtured by this trip, this secluded spot to which she has retreated.

Though Muriel proclaims herself a widow, there is more to it—a complexity to her grief that leans towards the metaphorical. More than anything, the person she must put to rest during this parenthetical trip is herself, or the version of herself that has been the source of so much pain and conflict. The protagonist recounts a scene from her husband’s novel in which a man must bury his dead friend—which, according to her husband, symbolises his own process of burying his child-self. That’s all very well, she thinks, but if that part of you dies, where does that leave me? Does that mean I must bury a part of me too?

Part of Muriel’s transformation over the course of the novella is the process of forcing herself to be vulnerable and helpless, to ask for assistance from others, combatting what she dubs as her “excessive firmness.” At the start of the story, the protagonist is unable—or refuses—to speak, responding to various people in the small town with simple gestures. She seems to hardly notice this at first, and indeed this is hardly noticeable to the reader either, only being revealed when it is pointed out by a teenager she meets on the beach. But she gradually regains her voice just as she grows into the ability to ask others to help her, from her temporary landlady to the supermarket delivery man. Admitting—to herself as much as to anyone else—that she must sometimes be reliant on others is an essential part of her metamorphosis. And this manifests in an increasingly physical way.

As the novella progresses, its sparse plot points grow increasingly surreal and erratic, and the reader begins to understand that this is no straightforward narrative. Beginning when the protagonist awakes to find a starfish clamped to her face then descending into an increasingly bizarre rabbit hole of events, the writing grows increasingly defiant of any attempts to understand it in simplistic terms. The narrative begins to feel as capricious and unmoored as the writing the protagonist blurts onto the page as she sits down to write each day—a task she insists upon completing, even if circumstances make this increasingly impossible. There is a blurring between author and protagonist, between the author’s writing and the writing within the writing. In the end, it is unclear if what we are reading is that writing within the writing, the author created by the author, who uses it as a form of processing, of grieving, of letting go and moving on.

The oddest element of this story is Muriel’s companion on her road to destruction and rejuvenation: a starfish (an Astropecten aranciacus) that she discovers on the beach outside her cottage. She encounters the creature on several occasions, and slowly, gradually, the starfish begins to approach her. Ultimately, it seems to bond inextricably to her, both emotionally and physically, sharing in her journey of self-regeneration. The physical transformation of the starfish mimics Muriel’s—did you know that starfish can regrow from a single arm?—and she often references its apparent love for her, love she comes to return by tenderly caring for the creature, keeping it in a bucket of water beside her bed.

In all its strangeness and surrealism, this novella is also a tender portrayal of motherhood. Muriel’s daughter Mar is a constant presence in the narrative, never an afterthought or a nuisance, but always grounding the protagonist in the here and now. Amid all the change and transformation Muriel must undergo, her love for her daughter and her ability to care for her remain intact; though she doubts many other facets of herself, she never doubts her desire to be her daughter’s mother. While she chooses to bury and leave behind one side of her mother-self—the side that chose to stifle and suffocate her husband with excessive nurturing—the entirely separate mother-self that is a steadfast parent to her baby daughter is as alive and well as ever, unaffected by Muriel’s physical state.

Villanueva’s work is as powerful as it is poetic, masterfully rendered into English in a deft translation by María Cristina Hall and Megan Berkobien (both past Asymptote contributors). This is an author with surprising breadth of skill, having produced a broad spectrum of works ranging from children’s literature to poetry to short stories, and this novella is a work that resists easy categorisation, drawing on a fragmented style and weaving in elements of surrealism. The illustrations by Aitana Carrasco, an unusual but beautiful addition to this book, evoke a storybook wonder, reminiscent of a fable or fairy tale. The novella is slim, just over a hundred pages, with not a word wasted—and it is a joy from start to finish.

Rachel Farmer lives in Bristol, UK, and works as a translator, conference interpreter, and editor. Her literary translations have been published in No Man’s Land and SAND, and in the anthology Elemental from Two Lines Press. Her translation of an extract of In Foreign Lands, Trees Speak Arabic by Usama Al Shahmani will be published in 2022 as part of the +SVIZRA series from Strangers Press. She also writes book reviews for Lunate magazine.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: