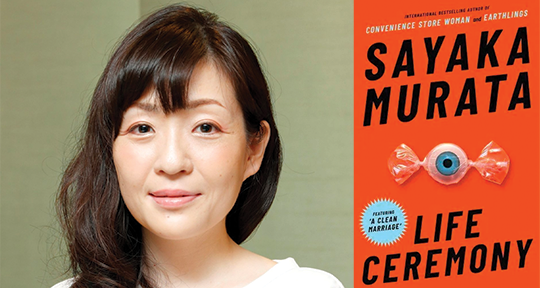

Life Ceremony by Sayaka Murata, translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori, Grove Atlantic/Granta, 2022

From Sayaka Murata, the award-winning author of Convenience Store Woman and Earthlings, comes Life Ceremony, a debut compilation of her short stories. The collection is unsettling, paved with the disturbances of odd people and new customs nestled amidst familiar words and routines;. Instead of burials, human bodies are recycled—a beloved father-in-law’s skin might be used as a bride’s veil, a person’s hair for a cardigan, human bones for chair legs. Instead of funerals, there are life ceremonies, where mourners dress in “skimpy clothing” to partake in eating the body of the deceased before going off in pairs for “insemination.” One woman is convinced that she has been reborn into an ordinary family in contemporary Japan, when in her previous (real) life, she was a warrior with supernatural powers from the magical city of Dundilas. Another woman falls in love with her curtain and feels betrayed when she walks in to find her boyfriend (who somehow has confused it for her) wrapped in its folds on her bed.

Sayaka Murata is a master of delivery, and in Ginny Takemori’s translation, it becomes clear that the way to convey these odd stories in all their philosophical force is to do it deadpan, matter-of-factly, and sometimes, coldly. But—there are breaks, moments that aren’t so much characterized by their coldness but by their sincerity, their characters’ confusion, and their loss. When Naoki, who is ethically opposed to using furniture or clothes made of human corpses, faces his late father’s dying wish to have his skin used in his son’s wedding, he is thrown off balance and says vacantly: “I can’t. . . I don’t. . . I really don’t know what to think anymore. Until this morning, I was confident about how to use words like barbaric and moved, but now it all feels so groundless.” We are made to sympathize with him even amidst bombardments of oppositional, universal ideas, derived from a new ethics that says discarding any part of a human is wasteful—one that asks: how is using human hair any different from using another animal’s?

In “Life Ceremony,” Maho can’t bring herself to partake in the ceremonial eating of the dead following an instance, thirty years ago, when she was bullied for suggesting the very thing that everyone does so casually now. She says to her friend Yamamoto, who also doesn’t eat human meat: “It’s just that thirty years ago, a completely different sense of values was the norm, and I just can’t keep up with the changes. I kind of feel betrayed by the world.” I too felt betrayed by the world in Murata’s novel, suddenly becoming painfully aware of how fast change comes via contemporary mediums—how many of our habits and values are dictated by global capital, and how much effort it takes to resist, even if only for the reprieve of a few moments to think and form opinions. How lonely it is both to belong to a world like this, and to be an outlier.

But there are also characters that move beyond hesitation and confusion, choosing to opt out entirely. In “Eating the City,” Rina, unable to stomach the awful vegetables sold at the grocery stores in Tokyo, begins to harvest her own dinners of wild vegetables all over the concrete city—dandelions, obako and fleabane leaves. At the beginning of the story, she reminisces about her childhood in the mountains, where her father picked wild strawberries and ate the sparrows he shot himself, and she realizes that her life has turned out entirely unlike the one she expected for herself. “Wouldn’t it be nice,” she muses, “if I could take evening walks and pick my own food, the way my father did.” As she begins to do that, she realizes after some time that hunger sharpens her senses; she can gather plants far more effectively when she hasn’t eaten, and she knows where to look. As the days pass and her excursions become a daily activity, she remembers that she likes the way her sneakers look when they’re covered in dirt, and she (re)learns how to “walk like an animal.” Slowly, in Rina’s new relationship with the city around her, it begins to shed those “artificial symbols” she has grown to see. Readers get the sense almost immediately that Rina is more than just nostalgic, that she remembers more than what she is aware of—something older, something primordial. Soon enough, Rina learns to see even inanimate objects, cold buildings and crowded taxis, as emitting warmth and sounds just like other “life-forms in the forest.” She makes it her mission, then, to make sure that everyone around her feels the same way.

“Body Magic” also features a character, Shiho Hashimoto, who has chosen to step away from the status quo by ignoring it entirely, and, when her classmates come dangerously close to ruining “something really important to [her] by turning it into a laughing matter, ” perks up the courage to mutter something like an incantation in response. Her friend, and the protagonist of this story, finds relief in her relationship with Shiho, and an escape from classmates who insist on “talking dirty” with her. For the protagonist, these classmates are worldly and mature, but something—though without Shiho, she can’t discern what, makes her very uncomfortable. . “Somehow I get the feeling,” Shiho explains, “that if you talk too much about it, you might know how to kiss, but you’ll no longer be able to kiss your own way.” The finality of this statement might be understood as childish naivete of , but it also, it drives home something Murata illustrates multiple times over: that we are a consequence of the external factors that have seen us through our lives, the people who surround us, their conversation, the food on our tables and in our bodies, the furniture in our houses, and that certain truths—ethics, world views, lifestyles—are very difficult to regain once they are lost.

Over and over again, throughout these stories, we are confronted with the question of consumption, literal and figurative. Some of Murata’s characters eat human meat while others refuse to; some insist on using corpses for furnishings and others reject the practice entirely; they eat wildflowers that grow around their city or cook food from magical cities; they either ignore their peers completely or adopt one of five new personas to please them. But it would be a disservice to Murata’s work to suggest that she is only concerned with the question of moral ambiguities and whether morality can be universal or timeless. While Murata does push the question of what it means to live an ethical life to its extremes and upsets common social standards without providing any final conclusions, what is most compelling in her collection is how each story pushes us to consider, and then re-consider, who and what we consume; what we allow to become a part of us, to make us—and in her refusal to provide any ready-made solutions, Murata asks us to begin the collective work of coming up with an ethics that responds more fully, more mindfully, to our contemporary predicaments.

Ruwa Alhayek is a Ph.D. student at Columbia University, studying Arabic poetry and translation in the department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African studies. She received her MFA from the New School in nonfiction, and is currently a social media manager at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: