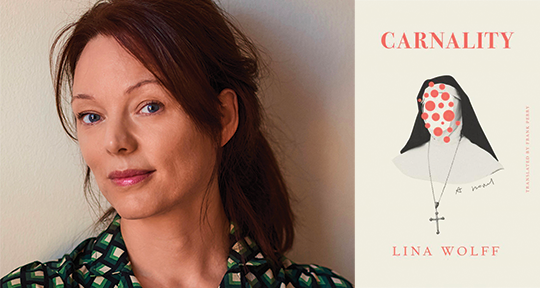

Carnality by Lina Wolff, translated from the Swedish by Frank Perry, Other Press, 2022

God was not really dead when Nietzsche proclaimed it through his speaking-box of Zarathustra. The sage of the German philosopher’s negations was, in fact, cementing the divine being in the noumenal; Nietzsche treated the death of God not as a state of things, but as a verb. It is not a death in the fact of non-existence, but an assassination. God is trapped in that liminal state of dying, and we are its killers, perpetuating the ongoing lineage of a refusal to believe. This is the way it was a hundred years ago, when atheism was radical and conscious, when a lack of faith had to make its way forward by obliteration, when such words had teeth.

In contrast, despite a nun being the prime orchestrator of events in Lina Wolff’s Carnality, God really does seem to be dead, a fact that no one fixates on because it would be like penning a manifesto of the Earth being round. Amidst the vast moral quandaries that swirl through the text, the ancient lessons and axioms that had once served as answers are nowhere to be seen, making room for that “ancient nobility” of chance to storm in between all those narrow spaces between us and the world, us and each other, us and ourselves. Adultery, caretaking, organ donation, euthanasia, murder—it’s all just happening. No choreography in the theatre of choice.

When a yet unnamed writer takes on a three-month travel grant in Madrid, she settles in the city the way one does in an airplane seat: procedural, passive, and with just a little bit of unarticulated dread. Having studied there in her youth, she is familiar with the city’s thorns and sieges, and from the first paragraph, we know—no one sane would choose to spend their summers in Spain’s capital. Still, small pockets of reprieve are there to be excavated: the ceaseless gurgles of wine pouring from dark bottles, the evening’s ink blotting some of the heat, the bright imagination of a city that holds newness in its oldness (“It’s down there. Life,” she thinks to herself). This transition of scenery outside the windows is settled quickly and efficiently in the space of a few pages, then Wolff draws the curtains, puts a drink in the narrator’s hand, and tunnels down into the strange, mutable basement-structure of story—a world which, its walls being made of words, shifts constantly with the mere logic of telling.

The novel aims its trajectories through odd and improbable scenes, which, when put to writing, morphs into something beyond rationality and comprehensibility; that is, it’s just life. Our narrator meets a man at a bar and, despite being repelled by his behaviour and abrasive way of making conversation, is compelled by curiosity. The man, tellingly named Mercuro, is erratic, shaken, and has apparently lost any sense of decorum. Immediately designating her home nation of Sweden as “the man-hating country,” he ignites a confrontation on the perceived militarism of feminists before backing down and asking for her forgiveness, then just as quickly follows up with a request to share her apartment for a few days—an arrangement that he assures will be non-romantic.

Absurd. Our narrator uses this word as well, but “an absurd idea is still an idea.” He plies her with the promise of a fantastic tale: one of a dissolved marriage, a commute to and back from hell, a maimed nun. It is both the dislocation from one’s normal settings and the forceful greed of writerly instinct that slow her from rejecting Mercuro outright. She’ll sleep on it. Freedom, too, is a rationalisation, one that we use tempestuously to justify our various natures. To replace that wagging finger of should with the shoulder shrug of could. The defiance of why-not can be decisive and almost beautiful to a woman—especially when her feminism, and thereby her hard-won authority—has been threatened. To not have to arrange one’s pathways along the same, tired schematics, to be seduced by the subversive nature of the absurd—it is her right.

The next day, she heads to a pool and is confronted by another substantiation of the world’s laws. If Mercuro had presented the tactical currency of power between a man and a woman, the scene at the pool is the obverse: a pure, sacrificial portrait of devotional love. A wife is taking care of her impaired, barely lucid husband with superhuman patience and detail to attention: “. . . that very rare thing: two people who share both great suffering and great happiness.” Deeply moved—to both compassion and envy—by the older woman’s joy, beauty, and elegant selflessness, she meets her next turn of chance when the need for an extra caretaker is overheard. She volunteers herself. The older woman, Miranda, is appropriately suspicious before moving into an elaborate interview process, but when the narrator forfeits any payment, Miranda becomes similarly touched in turn, and tears up as she denotes this kind stranger a “godsend.”

Our narrator doesn’t fixate much on this word, besides stating that “[n]o one has ever called her that before.” But in its use, Wolff further entrenches the modern discomfort of our ethics: if our compassion is not an indication of sacred resonance, where does it come from? How can we trust it? When Simone Weil reached this same station in her cartography of goodness, she responded by stripping the metaphysical barriers between us and the absolute. For her, the woman who essentially starved to death because she could not bear to deprive another of food by feeding herself—consideration of personhood is the inhibitor of goodness. Morality should not be established on the value of any individual person, but on the fact that they are any person, scaled on an extreme and unconditional equality. She substantiated this with her theory that there is divinity in mere humanness, masked by the corruption of individuality. As much as she hated the failure of language to talk about these things with precision, she posited that impersonality is our sacred nature. Weil didn’t like Nietzsche; she loved Jesus. She resurrected god and put it in every single human body that walked the earth.

The narrator is at least partially inspired by her new title of “godsend” to call Mercuro and accept him into her home. Once he is there, he rolls open the lurid revelations of his story as per their contract. Venturing into the disintegration between reality and media, the organic violence of betrayal and desire, the incapacity of forgiveness, and the incomprehensible terror of sacrifice—his tale is truly a scintillating one, complete with wistful musings on the waxing of genitals and noir appearances by villainous Chinese businessmen. In short, he had cheated on his dying wife, betrayed his lover, and was trying to amend it all on an underground webseries that gives the novel its title. The show consists of two individuals, one male and female, engaging him in a form of counselling that seems to be as effective as any Dr. Phil-esque talk show—which is to say, the results are determined by the audience’s appetite. It soon becomes clear by the bizarre and grotesque consequences that the audience was hungry for Mercuro’s abject humiliation, and—because Internet-speak truly seems to have no comprehension of mortality—his death.

Carnality is appropriately fixated on the body. The body as vessel, as statement, as dispute. The body as something that can be given and taken away. Wolff wrestles with the way our physicality at once controls and evades us, our unanswerable desires, our fleshy vulnerabilities. The many ways this simple border of skin can be trespassed are outlined in their multiplying forms, whether it be a look, a caress, a penetration, or an attack. It all seems at once terribly wrong and unavoidable, that our physical selves are in constant negotiation of custody, and we can never truly rescue its material from what lies beyond. All the distinctions that we’ve made with our mental and spiritual aspirations are in some way attempts to overcome the fact that we are bound to the worldly, to the carnal, that we only experience via the tenuous medium of physical presence. The imminency of sex, the eruptions of violence, the disintegration that ticks by alongside time—we understand so little of it, and yet are at the mercy of its speculations. By disrupting this façade of authority, Wolff is working towards a deeply frightening truth: that our bodies cannot be moralised or legislated because the fact of our human bodies opens the door for inhuman acts to occur, and no one knows why.

I hesitate to characterise Wolff’s writing as écriture feminine, not because I believe the typification to be oppressive, but because it would falsely give the impression that Carnality is centred on the female body, or the female experience of moving through the world. Wolff drags her letters through a multiplicity of corporealities—male and female, yes, but also immobile, aged, sexless, mutilated, and animal. (Some of the most harrowing passages in the book concern an increasingly industrialised abattoir.) The existential suppositions posed towards the body are not based on strictures of gender but on the assessment of otherness, both perceived and felt. Every subconscious calculation we make when assessing a body different from ours is magnified, and every reaction—safely housed in the realm of fiction—is free of judgment. Carnality is a book of telling; all the characters are, in some way, desperately trying to diffuse their otherness by relentlessly divulging their perceptions, their reasonings, and their sensations. Talking—or writing—seems to be the only method by which the excruciating loneliness of being a single, physical body can be ameliorated. I must talk myself into you, the characters seem to be pleading. I must talk myself into you, and then I will know that I exist. It’s a familiar feeling, as anyone who has ever told a story will know.

Storytelling lends Carnality a road-trip quality: conversations implant themselves into landscape and therefore become landscape. You get to see a world this way, such that the larger backdrop of this phenomenological map is only glanced once the story ends. It allows for a slightly more resigned nature of reading, one that encourages listening. Frank Perry’s translation is sensitive to voice, tactile and kinetic. One can almost see a knee bouncing to the rhythm of a sentence, a hand that gesticulates in the air.

The biggest moral tangle at the centre of Carnality surrounds merciful death—or, if mercy is too turbulent a word, justifiable death. The nun, Lucia, who stirred Mercuro into the maelstrom of his troubles, has a side business: one that offers permanent relief to those who desire it. Having been the recipient of a divine vision in her childhood, Lucia began to see herself as a saviour of the peoples, a revelation which then became the license to do whatever she saw fit to help. As she explains to our narrator:

It isn’t always possible, you see, to help people if you insist on never shedding blood. This depends, in turn, on how thoroughly you want to immerse yourself in the process, how far you are prepared to go to actually provide relief, and, of course, how brave you are. I have never been someone interested in half measures, so I was prepared to risk everything to follow the voice I thought I could hear inside me.

We never find out what our narrator’s response is to Lucia’s self-guided mission, for this section of the book is a one-sided epistolary, which allows it to be written with so much righteousness and assuredness that it’s hard to wedge a moral denunciation in. (It’s strange how much the world changed when we stopped writing letters, being then given the luxury of interrupting one another.) When Lucia does drop a hint at how not every death she sublimates is perhaps as consensual as one would hope, she stabilises it by emphasising her sacred call: “I have always believed that you have to be the master of your fate and the captain of your soul . . . and that of all the people He may choose to help, God prefers to choose those who can help themselves.” Through Lucia’s letters, we find out our narrator’s name—Bennedith, only a yawn away from that precarious word, blessing.

The dark side of justification, and the wound in the middle of Weil’s insistence, is that the ones trying to do good can never quite rid themselves of disdain towards those who do not. There’s a reason why the gods closest to us are the Greeks; we understand them because they hold so much contempt towards us—feeble, unmiraculous beings. On the show, Mercuro faces two people who make no secret of their superiority, and it is because of this affirmation that grants them the ability to help. When this hierarchy is unveiled, the power to do good is revealed to be just that: power. Power which dictates that one’s own goodness is morality exemplified. Euthanasia, or the sanctity of life, is not the question in the margins; the ambiguity here is with the rule. In our hand-me-down ethics, inherited from the Enlightenment, there is a distinct value of the mind’s ability to think over the body, and therefore to think itself into governing the body—not just our own, but those of others. The danger, then, when the carnal is relegated into the realm of sin and frivolity, and the mind is fooled into thinking it has total authority, is that we win an ability to rationalise ourselves into someone else’s life. Someone else’s body.

When Nietzsche said, “life simply is will to power,” it was a demand for us to come to terms with the fact that every action we undertake is felt by others, if not in charges, then in echoes. It is strange to look at all the abstractions that rule our physical beings today—all the regulation of entrances and exits, all the various codes and laws both secular and religious, all the discrepancies between infrastructures that supposedly keep some safe by entrapping others—and to feel our power wither next to theirs. Carnality meets such architecture in its shadows, this legislation purported to answer questions no one can put language to. It makes sense that Nietzsche called the overarching system of human existence chaos, and Weil called it love; such are the only two revelations in the world that turn every question mark into a period, every puzzle into a painting, and every human absurdity into a reason to live.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor. The chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, was published in 2019. The full-length collection, Then Telling Be the Antidote, is forthcoming in 2022. shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: