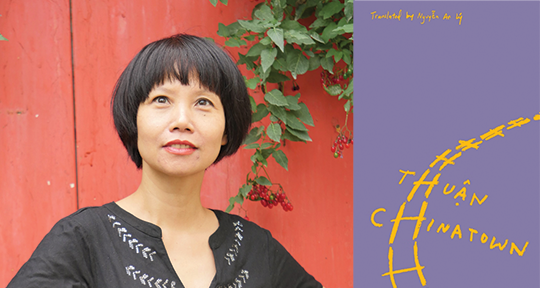

Chinatown by Thuận, translated from the Vietnamese by Nguyễn An Lý, New Directions, 2022

In an interview with Italian journalist Leopoldina Pallotta della Torre in 1989, Marguerite Duras revealed she had chosen the rather nondescript title of The Lover (L’Amant), her celebrated novel about a love affair between a fifteen-year-old French girl and a Chinese man in French Indochina, as “a reaction against all the books with that same title, [for] it isn’t a story about love, but about everything in passion that remains suspended and incapable of being named.”

In employing Chinatown as an equally unassuming yet versatile title for her 2005 novel, Thuận responds incisively to the Duras’s work from which she took inspiration by showcasing her pair of star-crossed lovers—an unnamed Vietnamese protagonist and Thụy, her ex-husband who is born in Vietnam but has Chinese ancestry. A Hanoi-born writer and literary translator living in France but choosing to write her novels—ten at last count—in Vietnamese, Thuận (full name Đoàn Ánh Thuận) deftly balances her complex content with a wryly confiding style. Making its English debut via Nguyễn An Lý’s incantatory translation, Chinatown’s generic title is deceptive, its compact length trapping layers of tensions to illustrate how political struggles in the public realm mirror emotional struggles in personal relationships. Subversive yet casually framed like a run-on conversation between friends, Thuận’s novel explores various iterations of Chinatown to convey exile, alienation, oppression, and artistic freedom.

Consisting of one vertiginous 184-page paragraph, the novel is compressed within a two-hour timeline during which the protagonist and her young son are trapped in a Paris metro tunnel while local authorities investigate a bomb threat. With nowhere to go, the protagonist soon launches into reminiscences spanning two eventful decades—from the last years of the Cold War to the period following Vietnam’s implementation of free-market reforms. As such, the novel is simultaneously expansive and claustrophobic, its experimental form disrupted only by two fragments from I’m Yellow, a novel-in-progress by Chinatown’s protagonist. This novel-within-a-novel structure embodies the ambiguous push-pull between oppression and freedom: Thuận’s protagonist roams ceaselessly yet neurotically in her imagination even as the main action is confined in both time and space.

Multiple dualities accentuate this core tension. Like the lover-as-intimate-other of Duras’s novel, Thuận’s concept of Chinatown suggests fluidity and/or liminal space: an ethnic enclave marked by displacement; an idea of home defined by exile; sanctuary constructed from oppression; emotional bonds born of alienation and vice-versa. Specifically, the protagonist’s marriage mirrors the complicated history between Vietnam and China. The couple meets as high school classmates and falls in love during the Sino-Vietnamese War, when China launched a series of attacks against Vietnam’s northern border to retaliate against the latter’s invasion of Cambodia. Despite speaking the same language and having similar cultures, the couple sees their eleven-year relationship severely impacted by this territorial conflict. Thụy’s career prospects are thwarted, his family members threatened with repatriation, and the couple’s marriage gone unacknowledged by their elders. After their son Vĩnh is born, Thụy leaves his wife and child for Saigon’s Chinatown. The pair eventually divorce, with Thụy remaining in Vietnam and the protagonist and Vĩnh emigrating to France. While remaining emotionally attached to Thụy, the protagonist never sees or speaks to him again after this relocation.

As with the struggles between the protagonist and Thụy despite their shared cultural backgrounds, factors such as geographical proximity and ethnic, cultural, and linguistic similarities have historically heightened Vietnam’s anxiety that it would never escape the influence of its norther neighbor (Vietnam was under Chinese rule from 111 B.C.E. to 938 C.E.) but remain forever the latter’s colonial outpost, or “Chinatown” in Southeast Asia. At the same time, this existential anxiety leads to Thuận’s criticism of both countries’ nationalist rhetoric as well as the West’s flattening gaze, which lumps all Asians into one undifferentiated mass. The protagonist is alternately forced to deny her Vietnamese heritage in a recurring nightmare where her son is injured and stranded in a Hunan-based hospital, while in her waking life she must endure the French’s misperception that she is Chinese:

The [hospital guard] shook his head. Yuenan [Vietnamese] children’s limb, go back to Yuenan to sew. Thụy said he was not Yuenanese, the child was not Yuenanese either . . . . Crying, I said I was not Yuenanese either. The guard still shook his head. Crying, I shouted, bù shì yuènán rén [I am not Vietnamese]. He shook his head even more. Crying, I explained that I too was an Âu. You don’t believe it, you can see my residence card . . . . But at the French embassy I have been madame Âu from the moment I showed up in the visa office. In Belleville I have been madame Âu for the last ten years, comment ça va madame Âu. The doorman says here’s some China letter for you madame Âu. The doorman, who is from Portugal, thinks Hà Nội is a suburb of Beijing.

Âu—the Vietnamese rendering of Thụy’s Chinese surname—evokes Vietnam’s creation myth, in which the fairy Âu Cơ married a dragon king and gave birth to 100 eggs, representing 100 Vietnamese tribes. It also brings to mind the kingdom of Âu Lạc, an ancient state located in Vietnam’s Red River Delta, founded by An Dương Vương, the Chinese conqueror who annexed the Âu Việt and Lạc Việt tribes. Replete with historical and linguistic allusions, Thuận’s novel vividly illustrates the challenge of separating Vietnamese identity from that of China.

The conflation of “I” and “other” due to Vietnam’s tangled relationship with China brings to mind Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection, as outlined in her essay “Powers of Horror,” about grotesque and taboo subjects that humans repress out of fear or disgust. According to Kristeva,

the one by whom the abject exists is thus a deject who places (himself), separates (himself), situates (himself), and therefore strays instead of getting his bearings, desiring, belonging . . . . For the space that engrosses the deject, the excluded, is never one, nor homogeneous . . . . but essentially divisible . . . . A deviser of territories, languages . . . the deject never stops demarcating his universe whose fluid confines . . . constantly question his solidity and impel him to start afresh. A tireless builder, the deject is in short a stray.

The protagonist and Thụy are likewise “dejects” who have trouble clarifying their essence and cannot pledge their full loyalty to the Vietnamese (or Chinese) state. It’s not a mere coincidence that Thụy works as an architect; “a tireless builder,” in Kristeva’s theoretical framework, he has to devise new environments since his present community cannot accept his difference. If we read Chinatown broadly, Thụy’s Chineseness is simply a metaphor that can be extended to any idea or person considered by the Vietnamese government to be heretical. This shifting concept of the other ironically becomes a paralyzing force, preventing the protagonist and Thụy from being able to define either themselves or their love for each other:

We sat on a bank, the river not wide enough, the water not clear enough, he not brave enough to talk to me, I not brave enough to touch his fingers, exquisite fingers the like of which I had never seen, and our nights out from then on were always the same, on the bank of the Red River which was never wide enough, its waters never clear enough, sitting side-by-side in silence.

This is where Chinatown both deviates from and converges with The Lover. Duras’s narrator/alter ego has already attained self-awareness by the age of fifteen. The daughter of white, impoverished French settlers in colonial Vietnam, used to eating “garbage—storks, baby crocodiles—but cooked and served by a native houseboy,” Duras’s waif-like heroine knowingly puts on a man’s fedora to attract the attention of an older Chinese man with urbane French manners and a body that smells “pleasantly of English cigarettes, expensive perfume, honey . . . the scent of silk . . . the smell of gold.” This lover—although branded as “a filthy Chinese” by local French gossiping about the affair—becomes both the heroine’s doppelgänger and her queer object of desire. Despite being an Asian male, he embodies the French girl’s longing for a sensual Western lifestyle and her attraction toward her classmate Hélène Lagonelle. Ultimately, however, the shapeshifting image of Duras’s Chinese lover does not subvert but affirm the white gaze, his pliant otherness fulfilling a similar role to that of Thụy—a mutable heretic in the eye of the Vietnamese state.

Leaving Vietnam for the West does not necessarily bring Thuận’s characters freedom or happiness, for they cannot escape their marginalized status—itself a psychological version of Chinatown. After arriving in France, the protagonist and her son settle in Belleville—home to the second-largest Chinatown in Paris—and from there would make the daily commute, by metro, to her teaching job and his lycée respectively. In the protagonist’s new milieu, she is either labeled as “la chinoise bizarre” (the strange Chinese woman) by her white colleagues or else rendered invisible in a sea of immigrants. In her recurring dreams, “The East Is Red”—China’s de-facto anthem during the Cultural Revolution—is now a garish Oriental-theme hotel in the heart of Belleville’s Chinatown. History, when rebranded as a by-product of travel, assumes a banal and parodic quality.

Ultimately, the Chinatowns of Hanoi, Saigon, Paris, and elsewhere become, like the metro tunnel where the protagonist and her son are detained throughout the novel, symbols of impasse. The characters’ ceaseless quest for home, across continents and languages, reflects a trapped mentality: How does one live when deprived of love? When one’s complex history is either suppressed for political reasons or reduced to clichés by commercial interests, rather than being allowed to holistically reveal what Duras defines in The Lover as “all things confounded into one through some inexpressible essence”?

If the Chinatown of 1930s Saigon seems at once safe and liberating to Duras’s white underage heroine/aspiring writer, this idea of sanctuary remains elusive in Thuận’s post-colonial environment. The state’s insistence on ready-made orthodoxy and its aversion to complex narrative—despite a dramatic shift from Marxist ideology to free-market policy in the past decades—have not changed. As such, art still has to serve the state, shifting from propaganda in the Cold War era to advertisement in a market economy. Aesthetic expression—under the state’s relentless gaze—by necessity becomes both guileless and opaque, like an innocuous yet totemic image of Saigon’s Chinatown, “a two-storey house, a shop sign with Chinese lettering, a pair of Chinese lanterns.”

I’m Yellow—the novel written by Chinatown’s protagonist and related by a first-person male narrator— perfectly illustrates this interplay between concession and resistance. The narrator in I’m Yellow is an artist who paints formulaic paintings of cherub-like Vietnamese babies, resplendent sunsets of Hạ Long Bay, and romantic afternoons in Huế’s imperial city. His machine-like output is designed to fulfill a marriage contract that allows him to both provide for his family and terminate the union once he completes the requisite work order. Artistic production as depicted in I’m Yellow thus both acknowledges and refutes the power of the state. Kristeva’s concept of the deject/outcast, who must learn to navigate the space that both engrosses and excludes him, comes to mind. The protagonist’s male character can stray from, and/or resist the status quo by playing into its expectations.

Structurally, the I’m Yellow interludes serve as an egress, helping to resolve the emotional impasse in Chinatown’s main narrative. Instead of submitting to intractable forces that derail her marriage, the protagonist, in creating her male character, can now accompany him toward unknown destinations.

I’m Yellow also reflects the protagonist’s longing for honest discourse. Since in her marriage to Thụy, she has to resort to non-sequitur, hyperbole, and subterfuge—all part of “the Hanoian art of conversation” to protect their personal privacy:

I changed the subject. I acted as if I didn’t hear. I gave a non-answer. I told a blatant lie. To any solicitous question, I gave a solicitous reply. Six months after getting married, I now knew enough to make people bored, and to understand that when people are bored they leave me alone.

While in Vietnam Thuận’s protagonist has to employ misdirection to evade scrutiny from those who question her choice of a husband, the author herself, as a writer in the diaspora, has chosen a more transparent approach. Her decision to write social novels in Vietnamese seems consistent with her refusal to accept an award from the Hanoi Writers Association in 2017 as a protest against state censorship and in solidarity with Vietnamese independent publishers, dissident writers, and artists. The fact that Thuận’s novels have also been translated into French and English seems miraculous, since many trenchant works by writers from so-called minority cultures remain untranslated and thus unheard of by the Western reading public. One only hopes the cry of “I’m Yellow” can resound beyond the Chinatown of every continent.

Thuy Dinh is coeditor of Da Màu and editor-at-large at Asymptote Journal. Her works have appeared in Asymptote, NPR Books, NBCThink, Prairie Schooner, Rain Taxi Review of Books, and Manoa, among others. She tweets @ThuyTBDinh.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: