When Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke was a year old, the celebrated writer and critic Nikos Kazantzakis stood as godfather at her baptism. When she was seventeen, he published her poem “All Alone” in an Athenian magazine with a note saying that it was the most beautiful poem he had ever read. By her early twenties she was already an established poet. During the dictatorship (1967-1974), she and a group of younger poets spearheaded a new kind of poetry that grappled with the confusion and censorship of those years. Meeting regularly with the translator Kimon Friar, they produced an anthology of six young poets, one of the first books to break the self-imposed silence initiated by the Nobel laureate poet George Seferis in response to the colonels’ press laws. Linking the women poets of the previous postwar generation (Eleni Vakalo, Kiki Dimoula) to those of the generation of the ’70s (Rhea Galanaki, Maria Laina, Jenny Mastoraki), Anghelaki-Rooke stands out for the lyrical accessibility of her work. Hers is a poetry of flesh, indiscretion, and the divine all rolled into one. For Anghelaki-Rooke the body is a passageway anchoring the abstract metaphysics of myth in the rituals of everyday life. It is through the body that everything makes sense. As she once said in an interview: “I do not distinguish the soul from the body and from all the mystery of existence . . . Everything I transform into poetry must first come through the body. My question is always how will the body react? To the weather, to aging, to sickness, to a storm, to love? The highest ideas, the loftiest concepts, depend on the morning cough . . .” In commemoration of her passing last week, here are two poems of eerie clarity from her last collection in which it is already clear she is looking at the world “with other eyes.”

—Karen Van Dyck, translator

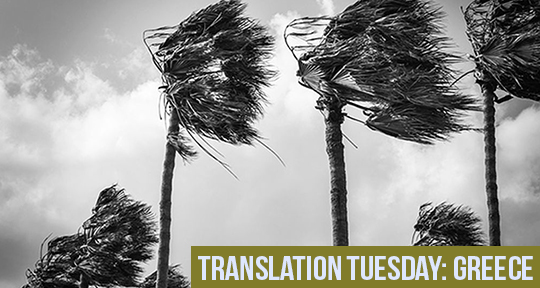

Epilogue Wind

Each time an act ends

humans feel the need

to write an epilogue

on paper or in the heart.

What was created by the mind

like lightening wants to shine

in the heaven of creation, to last

even if only in one small corner of history.

I find myself at that time of life

where I should “epilogue”

but I feel my past disappear

leaving only faint tastes and images

with no explanation.

The wind is there, though,

sometimes wild, sometimes cool,

carrying with it storms or calm.

Yes, the wind is the right epilogue

to a complete life

which, of course, when asked why

has no answer.

READ MORE…