In this month of highlights from the world of translated literature, we’re spotlighting three singular, wide-ranging, and immersive texts. From the Chinese, Shawn Hoo discusses the philosophical and journeying collection from celebrated poet Xi Chuan. From the Tibetan, Suhasini Patni reviews a dark, compassionate novel of womanhood and urbanity from Tsering Yangkyi. And from the Slovenian master Drago Jančar, Eva Wissting gives a look into his latest novel, on how personhood and identity survive the ravages of war.

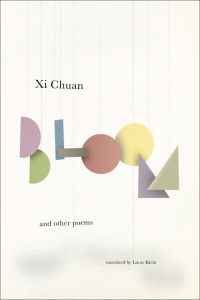

Bloom and Other Poems by Xi Chuan, translated from the Chinese by Lucas Klein, New Directions, 2022

Review by Shawn Hoo, Assistant Editor

In the title and opening poem of Xi Chuan’s (西川) Bloom and Other Poems, a simple verb like “bloom” begins lyrically and unsuspectingly enough—

if you’re going to bloom then bloom to my rhythm

close your eyes for one second breathe for two be silent for three then bloom

—but in the course of its exuberant and exacting repetitions across six pages, the action soon blossoms into a sophisticated geometry. At times, the verb seems to indicate an instructive concern for those new to the world (“bloom a pear blossom in case the nape of your neck is cold”). Other times, we hear the speaker issuing something of an injunction or a dare: “bloom / unleash a deep underground spring with your rhizome.” In a poem structured around insistence (to borrow Gertrude Stein’s understanding of how repetition works), Lucas Klein—who also curated and translated Xi Chuan’s Notes on the Mosquito—constructs a resonant architecture, allowing the echoes to bounce off the pages’ acoustics, often to rhapsodic effect: “bloom barbaric blossoms bloom unbearable blossoms / bloom the deviant the unreasonable the illogical” and later: “bloom three thousand boundless universes / and string up and beat any beast that refuses to bloom.”

In English, though not in Mandarin, bloom sits uncomfortably close to blood; in this titular poem, this simple word—across both languages—operates with an undertone of violence, belying its vivacious exhortations until the end, ending up as a verb that has swelled beyond its initial premise. The poems that come after “Bloom” all seem to share this restless inflation of the poetic image and line, each taking the verse to its various geometric limits, upon where it strains to meet other worlds. READ MORE…