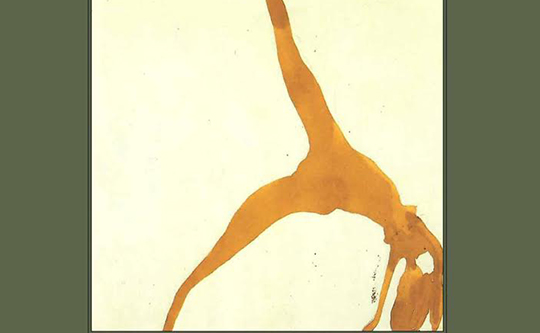

Poet-translator Jonathan Cohen has recovered these stunning translations of Pablo Neruda’s poetry, made in 1950 by the extraordinary Waldeen. Who? Learn about her and the secret of her translations in Cohen’s essay, “Waldeen’s Neruda,” appearing on our blog tomorrow. Here, published for the first time in this week’s Translation Tuesday, is her rendering of the complete “Coming of the Rivers” sequence. Comprising five poems, the sequence comes from the opening section of Neruda’s epic Canto General titled “La lámpara en la tierra” (“Lamp in the Earth”) in which he celebrates the creation of South America.

Coming of the Rivers

Beloved of rivers, assailed by

blue water and transparent drops,

apparition like a tree of veins,

a dark goddess biting into apples:

then, when you awoke naked,

you were tattooed by rivers,

and on the wet summits your head

filled the world with new-found dew.

Water trembled about your waist.

You were fashioned out of streams

and lakes shimmered on your forehead.

From your dense mists, Mother, you

gathered water as if it were vital tears,

and dragged sources to the sands

across the planetary night,

traversing sharp massive rocks,

crushing in your pathway

all the salt of geology,

felling compact walls of forest,

splitting the muscles of quartz.