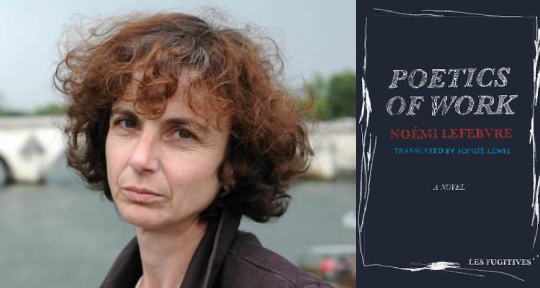

Poetics of Work by Noémi Lefebvre, translated from the French by Sophie Lewis, Les Fugitives, 2021

The deluge of our paroxysmal century has initiated a current in public intellectualism: a (only negligibly desperate) return to the texts that had attempted to reconstruct human thought and society in the aftermath of WWII, the total fracturing of order having led to a global crisis of aimlessness. I too, like many others, found myself, in the last year, grabbing my copy of The Origins of Totalitarianism in search of some clarity: “There are, to be sure, few guides left through the labyrinth of inarticulate facts if opinions are discarded and tradition is no longer accepted as unquestionable.” Though one wants to resist the striking relevancy of Arendt’s preface to the 1950s edition—“It is as though mankind has divided itself between those who believed in human omnipotence . . . and those for whom powerlessness has become the major experience of their lives”—it befits to understand its sustaining fact: our past is with us. Miles won by the powers of a corrupt engine are not achievements, but illusory, precarious compromises.

In Noémi Lefebvre’s Poetics of Work, the narrator is similarly attempting to decode the estranged world with resilient methods—reading (and re-reading) Klemperer’s The Language of the Third Reich, ingesting an extraordinary number of bananas, smoking what appears to be an unlimited supply of weed. Lyon, the city trembling in the background, is both a container and a newly unbreachable concept, reconstituting after waves of unrest caused by a proposed workers’ rights reform bill. There is a “strange new climate” that clots the senses, and one is struck, at the very beginning lines, by the great distances at the intersection between the private and the public. That we are trapped in our regarding, our helpless understandings, and the world, irreverent and oblivious, goes on anyway.

Poetics of Work wears its designation of “novel” like an alibi. It is not a story of a person, a place, or a time, and is entirely unconcerned with reality as a thing to be adopted or adapted. Instead, it is a radical assertion of the mind’s omnipresence, at once myriad and intact, the only entity capable of reconciling impossibilities—the physical with the abstract, the immense and the intimate, the existent and their ghosts in memory—by strange, incredulous methods of inquiry. By thinking. It is a transcript of the transcendental geometries created by thinking, as it flows and elevates, creating depths, creating beyond limits.

It is also, of course, an acknowledgement of the world going on, anyway. READ MORE…