Barbara Bray was a British translator and recipient of the PEN Translation Prize in 1986. In addition to having translated leading French authors of her time, including Marguerite Duras, Julia Kristeva, and the correspondence of George Sand, she also translated works by two renowned female Guadeloupian writers: Simone Schwarz-Bart and Maryse Condé. Though her work has undergone criticism—notably by Condé’s husband and translator, Richard Philcox in an recent interview with us at Asymptote—the importance of her legacy and contributions to global literature, as Nathan H. Dize proposes in the following essay, should not be undermined.

In late December, I decided to go browsing at a used bookstore outside of Nashville to take a much-needed break from writing my dissertation. There are few things in this world more comforting than perusing the spines of books, never knowing what you might stumble upon. A few minutes into my trip, I found a hardcover copy of Maryse Condé’s Segu, translated by the late Barbara Bray. The dust jacket was pristine and its cover depicted a dying African man surrounded by his family beneath a pulpy font. I instantly knew that I had to buy it, having recently talked about the novel’s translator with a friend. Unfortunately, Barbara Bray’s name appears nowhere on the cover of Segu—not on its first edition or any subsequent editions—which led me to wonder, how do we remember translators when they are gone? What becomes of the many lives they’ve lived through the words of others? Since that day in the warehouse-sized bookstore in Middle Tennessee, I’ve considered how Bray’s translations of Maryse Condé and Simone Schwarz-Bart, Guadeloupe’s most prolific writers, might help us to remember her life and her contribution to Caribbean literature in translation.

***

Barbara Bray (née Jacobs) was born along with her identical twin, Olive, on November 24, 1924 in Maida Vale, not far from Regent’s Park in London. She was educated close to Maida Vale at the Preston Manor Grammar School in Brent and later studied English, French, and Italian at Girton College, Cambridge. After her university studies, Barbara married John Bray, a former Royal Air Force pilot, and they went to live together in Egypt, where Barbara took a position as an English teacher at the University of Alexandria in Cairo. In 1953, the couple moved back to London, where Barbara began a new job as a script editor for the BBC. In his obituary for Barbara Bray in the Journal of Beckett Studies, John Knowlson recalls conversations with Bray about her time at the BBC, when she and other producers had to fight with BBC executives and department heads to air avant-garde radio plays and programs, such as Harold Pinter’s radio plays. Three years before Barbara Bray left the BCC in 1961, her husband John died in a car accident, leaving her widowed and tasked with raising their two daughters, Francesca and Julia. After John Bray’s passing, Barbara met Samuel Beckett and the two began a multi-decade love affair in Paris that coincided with Bray’s entrée into the world of translation.

Most French literary critics remember Bray for her translations of George Sand and Gustave Flaubert’s correspondance, novels by Jean Genet and Jean D’Ormesson, and, most exceptionally, for her translations of Marguerite Duras (including the Prix Goncourt and PEN Translation prize-winner L’Amant/The Lover). While living in Paris, Barbara Bray also translated Simone Schwarz-Bart’s The Bridge of Beyond in 1974 and Maryse Condé’s Segu in 1987, both of which stand out in her translation career as two of the three novels from the French Caribbean that she translated. It may be impossible to know how Bray came to these translations: whether she was commissioned, or if she made the case for their translation into English as part of a feminist or activist translation practice that aims to foreground texts with critical perspectives on gender. The two possibilities are equally plausible, as Bray had developed quite the cachet as a literary translator by the time she translated The Bridge of Beyond for Atheneum in 1974. By 1972, she had already translated the likes of Duras, Jean D’Ormesson, and the future Nobel Prize winner J.M.G. Le Clézio. When Bray took on Condé’s Segu in the mid-1980s, she had just published her award-winning translation of Duras’s L’Amant to much acclaim.

Bray may have seen the possibility of translating two works from Guadeloupe as an opportunity to provide critical perspectives on themes surrounding women, families, and the wake of French colonialism—themes that course through Marguerite Duras’s œuvre. The Bridge of Beyond is a story about the many mothers and daughters of the Lougandor family, living in the rural villages of Guadeloupe, while Segu tells a multi-generational story from the height of the Bambara Empire in the early 1700s to its decline in the mid-1800s. When I compare certain sentences from Schwarz-Bart with Duras and Condé, I see Bray bringing out a similar feminist resonance with regard to maternity, girlhood, and power. Take these three, for example:

Man has strength, woman has cunning, but however cunning she may be her womb is there to betray her. It is her ruin. (The Bridge of Beyond)

How I came by it I’ve forgotten. I can’t think who could have given it to me. It must have been my mother who bought it for me, because I asked her. The one thing certain is that it was another markdown, a final reduction. But why was it bought? No woman, no girl wore a man’s fedora in that colony then. No native woman either. (The Lover)

Sira was alone with her fear and pain. Fear, because the previous year she’d had a stillborn child. Nine months of anxiety just to bring forth a lump of flesh into which the gods hadn’t deigned to breathe life. (Segu)

Although the three sentences are quite different in terms of style (the first resembles a proverb, the second is a first-person narration, and the third is a third-person narration), they all present the reader with the intimacy of women’s stories. Condé and Schwarz-Bart’s sentences reveal the sorrow of maternity, hinting either at the loss of self or the loss of a child. And, like in the entirety of her life’s work, Duras enables us to see those who are most often rendered invisible: children and indigenous women. By reading The Bridge of Beyond and Segu alongside, and against, Bray’s numerous translations of Marguerite Duras, we can see why she felt compelled to take on the translation of these two particular Guadeloupian novels.

The first time I read a Barbara Bray translation was in 2011, during a graduate seminar, when we studied her translation of Simone Schwarz-Bart’s Pluie et vent sur Télumée Miracle/The Bridge of Beyond (1972/1974). The Bridge of Beyond was seen as a literary feat when it first appeared in French. Not only was it the first novel that Simone Schwarz-Bart published as a single author (in 1967, she published Un plat de porc aux bananes vertes/A Dish of Pork with Green Plaintains with her husband André Schwarz-Bart), but it was also well reviewed by Maryse Condé in Présence Africaine as an “undeniable success,” and was subsequently rewarded the Grand Prix des Lectrices by Elle Magazine in 1972. The prize, whose laureates have included international bestsellers Suite Française (Irène Némirovsky) and The Perfect Nanny (Leïla Slimani), ensured that Schwarz-Bart’s début would be a hit in translation. It was eventually translated into twelve languages.

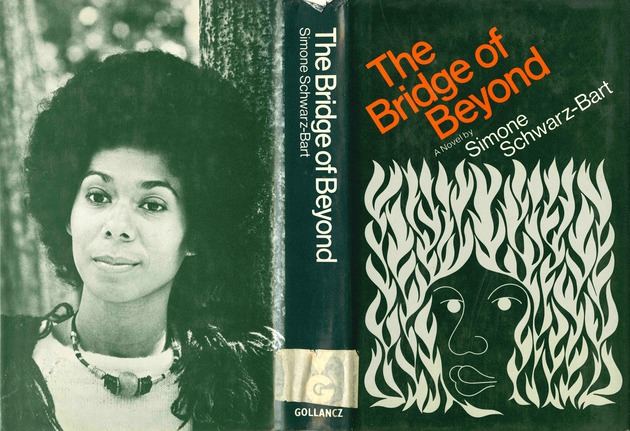

Pictured: Dust jacket of The Bridge of Beyond (1975) in the UK edition published with Gollancz. (Image credit: The Digital Library of the Caribbean)

Once Barbara Bray’s translation appeared in English with Atheneum Books in 1974, it was reviewed in various outlets, from academic journals to newspapers, but these reviews seldom mentioned Bray beyond the formatted citation at the beginning of the piece. The Bridge of Beyond was reviewed, along with four other books, in the New York Times by Paul Theroux in 1974, without any mention of Bray aside from the usual bibliographical information included in all book reviews. Theroux is drawn to the novel’s pastoral imagery, Schwarz-Bart’s talent for describing Guadeloupe’s tropical flora, and all the other elements that lend the novel to the notion of an exotic idyll—what about Bray’s knowledge of tropical flora and her ability to carry forth this imagery for Theroux and other readers in translation?

When The Bridge of Beyond was reissued as part of the renowned Heinemann Caribbean Writers Series in 1982, Wolfgang Binder meaningfully acknowledges the role that Bray plays in translating Schwarz-Bart’s début novel. Binder writes that Bray’s translation “does remarkably well in capturing the poetic texture of the narrator’s (Télumée) account.” When the novel was re-issued in the United States with NYRB Classics in 2013, reviewers mindfully commented on Bray’s 1974 translation, affirming that it has stood the test of time and recognizing the late translator’s contribution to Caribbean literature in translation. The Guardian called the translation an “immersive experience” and Sara Wilson of World Literature Today wrote that the novel and its translation “hold up well . . . confirming the novel’s status as a tour de force of Caribbean literature.”

While most of the reviews of the NYRB Classics have a great deal of reverence for Bray and her “brilliant” translation, reviews can be an awkward medium to commemorate the work of translators. For example, one reviewer for The Daily Beast failed to notice that Barbara Bray had passed away three years prior to its release in February 2010, blindly labeling the novel “newly translated by Barbara Bray.” Additionally, when Bray’s translation of Schwarz-Bart’s Ti Jean l’Horizon/Between Two Worlds (1979/1981) was reviewed by Darryl Pinckney in The New York Times, he failed to acknowledge Bray’s work and torpedoed Schwarz-Bart’s novel, which was praised in the French press, potentially contributing to the fact that there have been no new translations of her fiction since. Perhaps ironically, Pinckney critiques Schwarz-Bart’s novel about a voyage to an imaginary African past in terms of fidelity, an empirical mode of gatekeeping quite familiar to translators of any era, arguing that its romantic portrayal of Africa runs the risk of patronization or plunder. If the reviews of Schwarz-Bart have anything to offer in terms of remembrance, it is perhaps a directive: we have to return to the work itself to acknowledge the merits of the author’s imagination and the translator’s dedication to carrying that vision from one language to another.

While Bray’s translations of Schwarz-Bart have invited both praise and ambivalence, the legacy of Bray’s translation of Maryse Condé’s Segu is even more complicated. Maryse Condé’s husband and one of her translators, Richard Philcox, has claimed that Bray’s translation was flawed and warrants correction. When asked about the influence of the work of other translators, Philcox explains: “I try to avoid seeking inspiration from other people’s translations and there is nothing worse than having to correct other people’s work, such as we had to do for Barbara Bray’s translation of Segu.” Like Philcox, Condé’s views on Barbara Bray’s translation are well documented. In a 1989 interview with the late Vèvè A. Clark in Callaloo, Condé remarked that “[the English translation] had no success, in spite of Charles Larson’s favorable review in the New York Times Book Review,” adding that she “thought the combined edition was a complete failure. Though, we’re hopeful that Ballantine’s softcover edition will change the situation.” Condé was right: Charles R. Larson’s review was quite favorable. Even though the novel was a commercial failure, Larson wrote that Barbara Bray’s “fluent translation” was, at least in part, responsible for the novel’s engrossing quality.

When it was initially published in France between 1984 and 1985 with Éditions Robert Laffont, Segu consisted of two separate novels: Ségou I – Les Murailles de terre (The Great Walls of the Earth) and Ségou II – La Terre en miettes (The Earth in Pieces). In France, the novels were bestsellers. They received favorable reviews from Le Monde, recommending them to lovers of literary sagas because they give “a history often misunderstood an unvarnished vision.” As a measure of its commercial success, by 1989 the French editions of Ségou sold more than three hundred thousand copies combined. Despite their success in France, the two-volume saga received mixed reviews in World Literature Today. In his Spring 1985 review of Les Murailles de la terre, Juris Silenieks of Carnegie-Mellon University appears to struggle with how to read the first volume of Ségou, comparing it to Carlos Fuentes’s historical novels instead of other portrayals of eighteenth-century Africa. Silenieks also claims that Ségou “does not rise much above the level of an inspired soap opera, failing to stop and reflect, to distill a deeper meaning from the chaos and absurdities that crowd the narrative.” The gendered implications of these cannot be understated, but, as the review of the second volume of Ségou shows, Silenieks lacked the proper frame for reading Condé’s novel. A year later, David K. Bruner reviewed the second volume of Ségou, calling it “strongly impressive historical fiction” and “a major addition to the world’s literary treasure” for its historical depth. What is more, Bruner argues that it is Condé’s refusal to pass judgement on events that take place in the novel that gives her third-person narration its power.

Neither Condé in 1989, nor Philcox in his recent interview with Asymptote, specify the particular faults in Bray’s translation of Segu but, in an interview with Emily Apter in Public Culture in 2001, Condé mused that the American publishing market had tabbed Bray for the novel despite her lack of expertise in African-based religion. “[Bray] may have been a very effective translator for someone like Marguerite Duras,” Condé explains, but “she did not have sufficient knowledge of West Africa, and there were evident lapses—choices of words and phrases that were wrong or went against the grain of the text. When knowledge of context is insufficient, translators must be counted as enemies.”

While it is hard to argue with Condé’s reasoning, especially in relation to the cultural knowledge necessary to properly translate novels with particular investments in cultural histories and religion, might there be another way to approach Bray’s Caribbean translations? There must be a way of acknowledging the care that Bray brought to her translations while simultaneously reckoning with their faults. For a woman who dedicated her life to the translation and transmission of impactful literature, Bray’s legacy deserves the attention that one might give an author themselves. First, we must take Condé’s words seriously, because celebrated English translators of Caribbean fiction still manage to replicate mistranslations of race and Afro-Diasporic religious culture (see Kaiama L. Glover on Jeanine Herman’s translation of Savage Seasons by Kettly Mars). As such, Bray’s legacy as a translator is worth further attention precisely because it will help us to better understand the impact of market-driven translations and how capitalism continues to contribute to the evacuation of careful cultural insights from the work in its original language. However, Bray’s legacy is also worthy of re-evaluation because the massive body of work she built up from the 1960s onward carries the feminist poetics and vision we can see when comparing her translations of writers like Condé, Duras, and Schwarz-Bart. Re-reading Barbara Bray’s translations might, ultimately, be the best way to remember her life.

Nathan H. Dize is a PhD candidate in the Department of French and Italian at Vanderbilt University, where he specializes in Haitian literature and history. He is the content curator, translator, and co-editor of the digital history project A Colony in Crisis: The Saint-Domingue Grain Shortage of 1789. With Siobhan Meï, he coedits the “Haiti in Translation” interview series for H-Haiti. He is the translator of Makenzy Orcel’s The Immortals (SUNY Press), Kettly Mars’s I Am Alive (University of Virginia Press, forthcoming), and Louis Joseph Janvier’s Haiti for the Haitians (Liverpool University Press, forthcoming).

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: