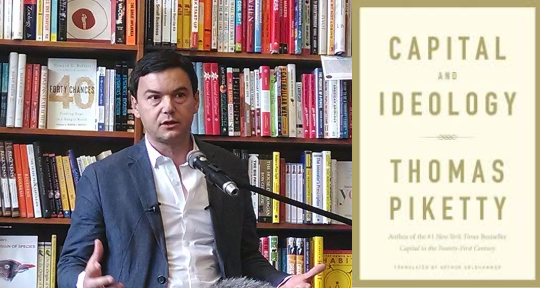

Capital and Ideology by Thomas Piketty, translated from the French by Arthur Goldhammer, The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2020

It’s rare for an economics book to make much inroad into non-academic circles, but the French economist Thomas Piketty did just that with his surprise success Capital in the Twenty-First Century, published in 2014 with an English translation by Arthur Goldhammer. This impressive work warns of the corrosive impacts of economic inequality, which has spiraled out of control in the last few decades. Piketty’s thesis—and perhaps the greatest success of the study—boils down to a simple equation: r > g, where r represents the rate of return on capital and g represents the rate of economic growth. Piketty warns of a future where returns on wealth will outpace all new forms of economic growth, entrenching all existing fortunes ever deeper, and only further those with more meagre supplies of capital. Piketty’s warnings seem to have struck a chord, although not without criticism. The global and historic scope of this study left many corners of the world understudied and with little room to understand the roots of inequality before the nineteenth century.

Piketty’s newest book, Capital and Ideology, again translated by Arthur Goldhammer, serves as a logical continuation of the project undertaken in his earlier research. If anything, it takes an even more ambitious approach to the seemingly intractable problem of economic inequality, offering both a diagnosis and potential treatments of our global malaise. Despite Piketty’s disciplinary background in economics, Capital and Ideology emphasizes the central importance of political and ideological change rather than changes in monetary policy or trade agreements. At his best, Piketty draws the potential dry discussion of economic systems into the complex interplay of human systems of politics, ideology, and history, and into the manifold ways these systems have taken shape throughout time and place. Perhaps most invigorating of all is the degree of faith Piketty places in human imagination and the ability to right wrongs and make active decisions to shape our collective future.

As he reminds us throughout Capital and Ideology, the accumulated wealth and power of the European elites in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries may have seemed intractable, and the political deference to the propertied classes total, but the century played out differently than many could have predicted at its onset. If the twenty-first century is to take such a path, global political and economic reforms will be necessary, and the range of ideological possibilities needs to be widened from those of the previous century. The crisis of the world wars and Great Depression coupled with new political mobilizations to rein in the influence of wealthy elites brought inequality to its lowest point ever. As Piketty likes to remind us, even Sweden, often bandied about as the paramount example of egalitarianism did not begin the twentieth century as such. In fact, he shows quite the opposite, where the amount of political representation in Sweden was proportionate to wealth. Nevertheless, the relative successes of social democracy were able to transform Swedish society in only a few generations. On the other hand, the relative equality of the postwar era has rapidly given way over the last few decades, showing no sign of slowing down.

The neo-proprietarianism, as Piketty calls it, of the last thirty years in many ways resembles the Belle Époque, or Gilded Age of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but Piketty refuses to simply look back nostalgically for solutions. While the global left seems hobbled, confused, and unable to articulate a coherent ideological challenge after the fall of Soviet communism, the goals themselves are not hopeless. Piketty stresses the importance of bold ideas and imaginations, and the need to find new discussions and movements that break from the ineffective and outdated tools of the nation states and their borders. The continued failure of political imagination has weakened confidence in our political systems, ushering a dwindling and disillusioned voting bloc to seek refuge in the easy promises of nativist politicians who promise that the borders of nations will salve the disappointments of the global age. Without new ideological alternatives, without political innovation, and without the ability to abandon the nation-focused solutions of the twentieth century, our present state is likely to endure.

Finding ourselves at this ideological impasse, Piketty posits Capital and Ideology as a necessary step for beginning the long process of public deliberation that the seeming global dissatisfaction necessitates. Despite its length and subject matter, Piketty proposes a broad audience for his work and not solely for economists, politicians, or experts. The division of expertise into hermetic cells prevents the kinds of productive discussions necessary in our age. Reams of economic data build the structure of Piketty’s argument; for those less quantitatively minded, much is shunted off online so as to not overwhelm the work as a whole. In fact, he warns that economics is perhaps blindingly devoted to mathematics and theorization while neglecting other sources. Piketty’s success lies in his ability to incorporate the erudite and statistical with a wide range of sources cutting across disciplinary backgrounds and interests. For those outside the realms of politics or social science, it’s important to remember that we too play an active role in this deliberation and have tools at our disposal to make a positive contribution. The arts are, after all, a realm of human imagination and ingenuity, capable of insights into social, cultural, political, and personal avenues. Piketty himself emphasizes the role the arts can play in our understanding of these sprawling issues, and their utilization lends a viable pathway for world literature and the arts more broadly to have a say in the deliberations necessary in this most current crisis. For the struggling academic, translator, or writer, it’s an important reminder that our voices matter in the most pressing discussions of our time.

Piketty utilizes a few illustrative literary examples to provide a specificity and immediacy otherwise unavailable in the reams of historical data and economic figures. Capital and Ideology seeks to understand the development, refinement, and reform of ownership societies that were increasingly formalized through rules and systems of ownership, inheritance, and property. He sketches a corresponding transformation in literary representations from the heroic, selfless, and community-driven values that give way to wealth as the ultimate social hierarchy epitomized by the social concerns of the literature of Honoré Balzac and Jane Austen. Wealth, investments, and rental incomes form the background of a social world where privileges of aristocracy give way to a new ideology of ownership and control, shaping a constrictive society dominated by the laws of capital. Only with the rise of finance and industrial capitalism does a new logic take shape with an ideology of merit to justify the inequalities of the era.

World literature helps Piketty conceptualize the kinds of social, political, and economic experiences of the proprietarian ideology on the lives of its subjects rather than masters. Colonial inequality is epitomized by Indonesian novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s historical novel This Earth of Mankind (1980). The novel’s protagonist Saniken learns to utilize and maintain a colonial plantation after its owner flees back to the Netherlands, but she finds herself never able to own what her labor produces. The legal channels of proprietarianism and inheritance dispossess and disempower her restoring the land to its supposedly rightful heir. For a more contemporary example, Piketty shows how the postcolonial subjects are themselves twisted by the perverse logic of propriety, pitting one against the other and upending their native hierarchies, but are ultimately victims of a political system seeking local answers to larger global dilemmas. In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2013 novel Americanah, protagonist Obinze, despite his education in his home country of Nigeria, enters into precarity as an undocumented migrant in the United Kingdom. Pressured by government crackdowns above, he finds himself preyed upon by other opportunistic migrants, who skim from his salary and ultimately turn on him, leading to his deportation. For Piketty, Obinze’s fate represents how even the British Labour party has acquiesced to the intractable ideology of our age, and his punishment shows a political system eager for quick and easy victims to blame. Yet he reminds us that there are no easy answers or scapegoats. The tide can be turned but it requires new ways of seeing and thinking about the world, and perhaps ways that consider the Obinzes or Sanikens having a participatory role in writing its new rules, of having a say in our collective value systems.

Where, once again, we find ourselves at an inflection point, thinkers like Piketty generate and agitate the kind of discussions needed to address our collective woes. Plunged into confusion by a global crisis, the friction of possible paths resonates globally, forcing us away from comfortable passivity to ask difficult questions. The global economic forecast is grim, unemployment numbers are troubling, and the ability to resume life as we once knew it is an indefinite uncertainty. More than ever, these difficult times require introspection. How did we get here and where will we go from here? Thomas Piketty’s Capital and Ideology grapples with these unwieldy questions as well as any one book can, leaving us a timely and potent passageway into some of the most pressing issues of our globalized age. While crisis exposes the fault lines of societies more starkly, perhaps it can also provide a new opportunity to draw plans and take an honest look at forging a new path.

Ian Thompson is an independent luthier, woodworker, and freelancer. He studied Scandinavian and Early Modern Literature at the University of California and has taught Comparative Literature and Global Studies at the Pennsylvania University. At present, he is researching craft, art, and labor for future projects interrogating values of work. Ian is particularly interested in the intersections of literature, history, and culture and in the pursuit of the interdisciplinary study of human systems. He is always looking for new projects and avenues to explore his interests and venues to share his passions.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: