2023 is already setting up to be one of the most wide-ranging and bounteous years for literary purveyors of the world, with an abundance of exciting works slated for publication. This month, we’re presenting three texts that enrapture the imaginative prospects of a world in translation: László Krasznahorkai subverts every expectation for the travelogue, Bachtyar Ali braids storytelling and truth-seeking, and Maria Adolfsson reasserts feminist presence in the male-dominated mystery genre.

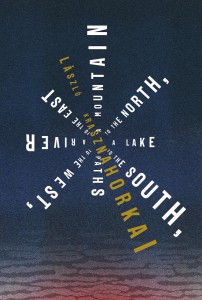

A Mountain to the North, A Lake to The South, Paths to the West, A River to the East by László Krasznahorkai, translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet, New Directions/Serpent’s Tail, 2023

Review by Matthew Redman, Digital Editor

László Krasznahorkai is among Hungary’s most feted writers in the Anglophone world. His works, characterised by inordinately long, slow sentences which chart the depths of obsession and madness, have earned him a cult of devoted readers and international acclaim, while his translators—Georges Szirtes and Ottilie Mulzet—are lauded writers in their own right. However, his most recent novel to be translated into English, A Mountain to the North, A Lake to The South, Paths to the West, A River to the East, is an intriguing departure from the works that have made his name. The vast sentences he is known for are intact, but they are used in service of a radically different tonal palette. Where his other novels use length to induce futility and despair, A Mountain to the North explores the beatific, languorous, and even beautiful possibilities of extreme syntax.

Set in Japan, the novel takes the form of a travelogue—albeit with the sheer mass of textual detail slowing the journey to an ooze. Strip this away and you find comparatively simple structural bones: a train deposits us at a deserted platform somewhere in Kyoto, we leave the station and wander half-lost through empty streets until we arrive at our destination, a Buddhist monastery in which we remain for most of the novel, touring the grounds and slowly penetrating the interiors. It is a balmy late afternoon, there are beautiful gardens all around, the monastery is silent and exquisite. This part of Kyoto is almost entirely bereft of inhabitants, but the emptiness is one of the rare details that Krasznahorkai chooses not to linger on. In fact, the absence is fortuitous, because the novel is uninterested in people; what consumes the author instead is the immutable, near indescribable beauty of things wrought in accordance with Japanese tradition. With the streets and monastery empty, the prose is freely devoted to the description of his sublime surroundings. Plants in their carefully tended gardens; the shrine’s architecture—their calculations and materials, the minutiae of their construction; the nigh-divinely sagacious prescriptions according to which every detail within the monastery was planned, planted, and built; the commitment at every turn to the tireless refinement of perfection; and above all the feel of all of this beauty—the texture and the grain, and the effect on the soul.

Each chapter houses a single enormous sentence that describes and extols a single beautiful object (a gate, a shrine, a statue) or craft (carpentry, gardening), and ends only when Krasznahorkai deems the subject exhausted. As demanding and unconventional as this novel is, it is not difficult in the way that experimental fiction is often thought to be. For all its density, there is a deceptive simplicity, even a solicitousness to Krasznahorkai’s prose. His sentences are slow enumerations in service of a simple message that never changes: the monastery and everything within it are perfect, and it could only ever have been so, for it is all the product of patient, genius craftsmen adhering immaculately to faultless prescriptions. The long succession of accounts of perfect things has an incantatory quality, the meticulousness neither torturous nor bewildering, but rather intended to soothe. Krasznahorkai wants to leave you tranquil:

[…] it was something like a labyrinth, of course, but at the same time the chaos causing the oscillation of the layout of these streets wasn’t frightening and even less so futile, but playful, and just as there were finely wrought fences, the grated rolling gates protected by their small eaves, above, leaning out from both sides here and there, were the fresh green of bamboo or the ethereal, silver foliage of a Himalayan pine with its firework-like leaves unfolding; they bent closely over the passerby as if in a mirror, as if they were protecting him, guarding him and receiving him as a guest within these tightly closed fences and gates, these bamboo branches and the Himalayan pine foliage; namely, they quickly gave notice to the one arriving that he had been placed in safety […]