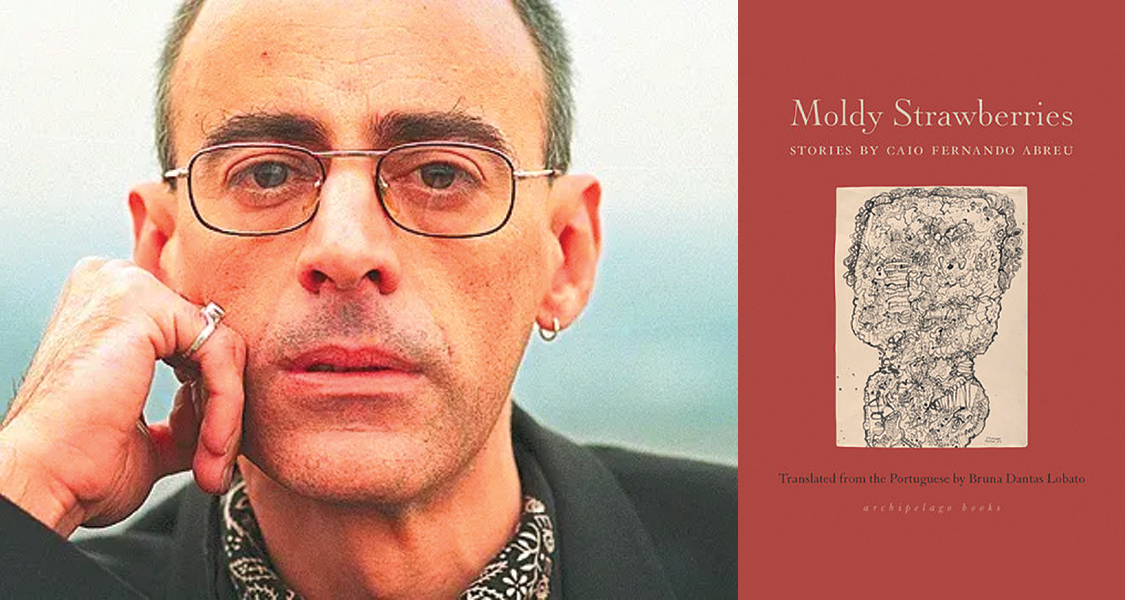

Moldy Strawberries by Caio Fernando Abreu, translated from the Portuguese by Bruna Dantas Lobato, Archipelago Books, 2022

Moldy strawberries: just past the point of ripeness, bursting with life until they exude decay. Sweet yet bitter, delicious yet spoilt, nourishing yet rotten. It is this dichotomy that sustains Caio Fernando Abreu’s Moldy Strawberries, tenderly translated from the Portuguese by Bruna Dantas Lobato: a collection of short prose pieces and stories that brims with life even as its flesh bruises.

Abreu (1948-1996) came of age in a turbulent time in Brazilian political history. In 1968, the Department for Political and Social Order put him on the watch list they used to target their ideological opponents, and Abreu subsequently spent time in exile across Europe—in Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands, England, and France. While his writing was heavily censored by the Brazilian authorities, he nonetheless became one of the country’s most beloved queer writers, winning the prestigious Jabuti Prize for Fiction three times for his luminous work.

Moldy Strawberries is considered by many to be his magnum opus. Published in 1982, its vivid depictions of queer communities amidst the perils of the military dictatorship, rising homophobia, and the looming AIDS crisis serve to affirm life even when the threat of death feels ever-present. In eighteen prose pieces, which range from dialogues and vignettes to fully developed stories, Abreu’s writing bears witness to humanity in all its fragile glory. His prose affirms the possibility of love, desire, and connection—or at least indulges that dream.

Abreu’s style is reason enough to pick up the collection. Tales are often told in a breathless manner, but the narrative will at times pause abruptly, as if the narrator needs to catch their breath after this dizzying display of emotion. Dantas Lobato matches Abreu’s pace with care, infusing the stories with an incredible affective power that lingers long after the book ends. The second story, “The Survivors,” is an exemplary introduction to Abreu’s style that narrates a failing relationship in strands of interwoven dialogue:

It could have worked out between us, or not, I don’t even know what that means, but back then we hadn’t figured out yet that you wanted to take it up the ass and I wanted to lick pussy, oh how adorable our books by Marx, then Marcuse, then Reich, then Castañeda, then Laing under the arm, all the foolish colonized dreams in our little idiotic heads, scholarship at the Sorbonne, tea with Simone and Jean-Paul in Paris in the ’50s, then the ’60s in London listening to here comes the sun here comes the sun, little darling, then the ’70s in New York dancing disco at Studio 54, now in the ’80s we’re here, chewing on this nasty thing and unable to swallow or spit it out or even to forget the sour taste in our mouths.

Abreu collages together an abundance of references, which has the effect of immersing the reader in the text. It is as if we ourselves are tangled in this messy relationship between two lovers who have lost the spark of eroticism while they go on a whistle-stop tour of the world, until Abreu brings us to a screeching halt in an unidentified city. This passage—indeed, the book as a whole—is so rich that its intricacies dazzle the reader with their kaleidoscopic world. One particularly nice touch is the soundtrack that Abreu suggests for some of these early stories, so that we listen to Angela Ro Ro along with the characters as their relationship disintegrates.

Even when employing a third-person narrator, the stories feel intimate and personal. The blurriness sometimes engendered by intimacy becomes central to stories like “I, You, He,” about the others who come to inhabit a relationship that’s ostensibly between two people. “What I see in others, with their big open pores, are faces full of vigor,” the narrator says at one point, making Abreu’s typical zoomed-in perspective literal.

Up close and personal, Abreu captures all the minor details that a close relationship can teach you about another—but also what it can teach you about yourself:

But our orgasm was the same, and in that moment we were one, us three, ridden by this man we exhausted with the thirst of our tongues. In moments like this, I knew your face as intimately as I knew his and my own.

Here desire is portrayed as a powerful force, one that erases the bounds between self and other, dissolving our subjectivity in moments of bliss and ecstasy.

But while queer desire is celebrated throughout Moldy Strawberries, it also comes with certain dangers for those living under a homophobic, patriarchal dictatorship. “Fat Tuesday” begins as a sensory explosion as it recounts a hook-up during Carnaval:

His tongue went down my neck, my tongue into his ear, before they melded together, wet. Like two ripe figs pressed tight against one another, the red seeds grating against one another like teeth against teeth.

Figs, like the strawberries of the title, are endowed with the lush vibrancy of desire, but the image of red seeds as grating teeth points to blood—an ambivalent symbol representing both life and death. The subtle refrain of “ai, ai, look at them queens” reminds readers of the undercurrent of peril, and the story ends with a devastating explosion of violence: “the slow fall of an overripe fig, until it met the ground in a thousand bloody pieces.”

At other times, however, Abreu flips the script, and what begins as a frightening environment gradually makes room for desire to surface. In “Sergeant Garcia,” the eponymous character is a menacing figure who explicitly brings politics to the fore in his conversations:

“Just can’t stand Communists. But thank God the revolution’s taken care of that problem. I’ve learned to look out for myself, Mr. Philosopher. To defend myself tooth and nail.” He tossed out his cigarette. His voice was soft again. “But with you it’s different.”

While we might expect a military man to exhibit violent homophobia or machismo, what follows instead is the story of Mr. Philosopher’s first sexual encounter: an ambivalent awakening, an initiation into a strange yet uncertain desire.

Some of the most poignant moments in the collection come from tales where our protagonists are lonely, perhaps even vulnerable, but where human connection allows genuine love and tenderness to bloom. “Those Two” recounts the story of two beautiful but solitary men, Raul and Saul, who work together in an office. A tentative friendship slowly transforms into an intense devotion, and while the story does not narrate any explicit sexual scenes, the love between them is obvious:

They stepped away from each other, then. Raul said something like I have nobody else in the world, and Saul said something else like, you have me now, and forever. They used big words – nobody, world, forever – and held both hands at once, looking into each other’s eyes, full of smoke and alcohol.

This story encapsulates Abreu’s finest achievement throughout the collection: the ability to narrate big emotions with “big words” while undercutting them with a self-consciousness that means these moments never feel trite.

Moldy Strawberries is without a doubt a sensory experience, with rich descriptions and references throughout the text. As well as the recommendations for music to accompany the reader’s experience, the narratives often hinge upon songs, lyrical motifs, or refrains that enrich the meaning of the text. Abreu mentions songs in English, Spanish, and Portuguese to create a multilingual soundscape, which understandably poses challenges for the translation. Dantas Lobato’s response is to create a multilingualism of her own, where the English text is peppered with words or phrases that maintain the cosmopolitan world that Abreu conjures up. In the romance between Raul and Saul, for example, musical language is left in Spanish:

Raul was the one who sang: “Perfídia,” “La Barca,” and at Saul’s request, “Tú Me Acostumbraste,” once more, twice. Saul especially liked that little part that went like this, sutil llegaste a mí como una tentación llenando de inquietud mi corazón.

[you came subtly to me like a temptation that filled my heart with restlessness]

Here Dantas Lobato is able to preserve the musical rhythm inherent to the Spanish song while offering a small reward for the reader who either speaks Spanish or is willing to do their research, as these lines enhance our understanding of the plot.

Reading Moldy Strawberries feels like immersing yourself underwater, in a beautiful world full of vivid colors and unfamiliar textures. While the current could drag you under–for danger and sadness are ever-present, the foil to vibrant love and desire–you surface feeling profoundly changed by your experiences. Abreu’s work bears witness to the beauty and cruelty of humanity, and in Dantas Lobato’s translation, they offer access to a dazzling literary experience that should not be missed.

Georgina Fooks is a writer and translator based in England. She is the Director of Outreach at Asymptote, and her writing and translations have been published in Asymptote, The Oxonian Review, and Viceversa Magazine. She is currently completing a master’s in Latin American literature at Oxford, specialising in Argentine poetry.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: