In this week’s edition of In This Together, a curated column bringing you literature in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Asymptote is proud to present a short story by the Hong Kong writer, Wong Yi. Below, translator Jennifer Feeley discusses Wong’s work:

This story is part of Wong Yi’s ongoing fiction series Ways to Love in a Crowded City, which captures how ordinary Hong Kong residents compress and contort their love lives in the face of various constraints. Aside from the title story, the short pieces that make up this series have been published in her online columns for the Hong Kong periodicals Ming Pao Weekly and Fleurs des lettres, with a famous painting inspiring each story.

When Wong Yi began this series in March 2019, she was initially interested in exploring how physical space and work culture impact Hongkongers’ romantic lives, but as protests escalated throughout the city later that year, she began writing stories capturing people’s changing behavior and attitudes, highlighting their feelings of anxiety, fear, and anger. Wong Yi explains, “It was my way of coping with a very challenging period of time, and keeping record of the unimaginable things that were happening. Unusual circumstances and political events had become another category of constraints on people’s lives and love.”

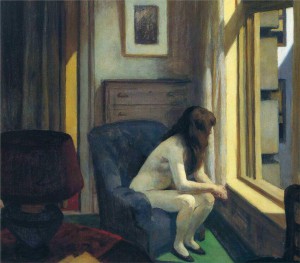

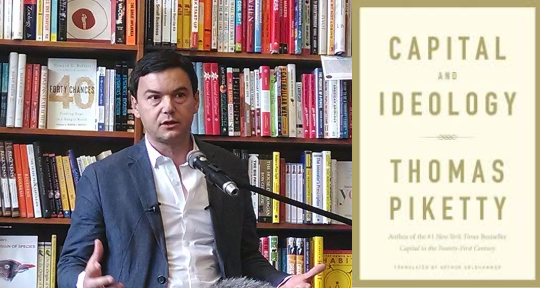

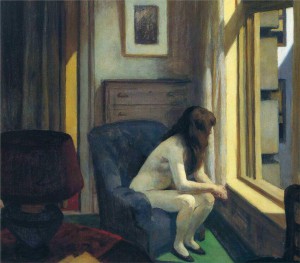

In early 2020, the pandemic broke out, superseding the protests as the new “unusual circumstance” affecting Hongkongers’ lives, and she ended up writing “Patient” shortly after her friend moved back to Hong Kong from Australia during the height of the outbreak. As the virus spread throughout the world, people began referring to themselves as being in Edward Hopper paintings, prompting Wong Yi to pair her story with Edward Hopper’s Eleven A.M. Whereas being physically together typically is regarded as an act of love, the story demonstrates how during a pandemic, having the patience to stay physically apart becomes a new way to demonstrate one’s love.

Patient

by Wong Yi

(After Edward Hopper, Eleven A.M., 1926)

I’m back in town, you say. It’s good you’re back, she says. But it’s not good, you think. During the past two months, the virus has spread throughout Hong Kong. She and others who’ve been living in the city have moved past the initial frenzy of shock and panic buying, gradually adapting to daily life under the pandemic. They’ve even started letting down their guard, loosening their masks and venturing out on the streets again; you’d been in Australia, listening to her report such things for two months, always taking on the role of comforting her, constantly offering to send her hand sanitizer or a small gift to cheer her up, urging her to stay home as much as possible to avoid infection, and then, in mid-March, not long after White Day, the outbreak in Australia finally began to worry you both. When people all over the world started buying up toilet paper and advocating staying at home to fight the pandemic, your roles were reversed. Have you bought enough food? she asked. Can you buy masks in Australia? she asked. Australia’s customs restrictions are so stringent—I can’t send you any food. Please take good care of yourself, she said. You solemnly promised her, I will. I’ll make it through graduation, and then I’ll come back to Hong Kong and we’ll “sweep street,” hitting up all the good food places. I’m going to eat fried stuffed three treasures, mango pomelo sago, buttered pineapple buns, and rice noodle rolls with sweet sauce, you said. Okay, when the outbreak is over, we’ll go eat, she said. You talked to her over video, virtually hooking pinkies. A few days later, while you were still contemplating whether to be a dutiful daughter and heed your mother’s advice to buy a plane ticket back to Hong Kong, seeking refuge like other overseas students, she said she saw that confirmed cases in Australia were continuing to climb, and she was concerned for your safety, and so that very day, you made up your mind to pack up your belongings and booked a room in a Hong Kong hotel that previously had been used to quarantine university students returning to the city from the mainland. The next day, you cocooned yourself in a windbreaker, gloves, glasses, and a mask and flew back to Hong Kong, every nerve on edge, embarking on your life of fourteen days of hotel self-quarantine.

It’s good you’re back, she says. You feel the same way when you close the hotel door. A few days later, Qantas goes as far as grounding all international flights—if you hadn’t already returned to Hong Kong, you probably would’ve had to swim back. At least now you’re both in the same city. Even if the whole world is caught in the same war-like disaster that’s turned the planet on its head with absolutely no end in sight, at least you’re back, and from now on you can live and die alongside her within the borders of the same city. She makes you promise her you won’t set even half a foot outside the hotel for fourteen days. She’d rather use up a mask shopping for the numerous Hong Kong snacks and soft drinks you told her are your favorites, dropping them off at your hotel and asking the staff to deliver them to your door, tucking inside a few extra goodies to brighten your hotel stay: a card to boost your spirits, hand sanitizer, Japanese sheet masks, and nail polish. When you open the overstuffed plastic grocery bag, you can’t help but sweetly smile and tear up at the same time: Doll pickled vegetable and pork instant rice noodles, Four Seas toasted seaweed, Sze Hing Loong dried seasoned cuttlefish, Vita lemon tea, and Garden Lemon Puff cookies—she’s remembered them all. She says, C’mon, of course I remember! You think your hunch is really spot-on; she must like you too, since she remembers every word you’ve said, and you remember every word she’s said. READ MORE…