Writing has always been a refuge of resistance for those living under oppressive political regimes, such as under the Romanian dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu. Often, such writing creates a movement, a group whose literature has much in common, emblematic of the particular circumstances of its birth. In Romania, this was “desk drawer literature.” Yet, of course, writers within such movements also retain their individuality—and some more so than others. Whilst many authors of Romanian dissident literature exiled themselves in other European countries or the USA, I.D. Sîrbu remained in his native country. Little known in the English-speaking world, Sîrbu was a prolific, versatile, and unique writer of plays, short stories, and novels. In the following essay, Andreea Scridon, whose translations of Sîrbu’s selected short stories are forthcoming with AB Press, discusses his life, work, and fascinating singularity.

The phenomenon of subversive literature, either containing subversive content or written in subversive circumstances, is characteristic of twentieth-century Eastern Europe. In a nightmare that nobody predicted would ever end, writing continued to represent a flame in the cavern, a stubborn desire to keep actively participating in life, despite the forced degradation of the spirit by the regime in power. Romania’s dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu, astutely aware of literature’s power of influence, issued a statement summarizing the attitude of the time: “It is to be understood, comrades, that we are the partisans, from the beginning to the end, of a MILITANT literature and we do not even conceive another kind of literature.”

It was in this context that “desk drawer literature” was born: literary work that was written for its “integrity,” as Solzhenitsyn puts it, and not for the ego boost of being published. Names that have now become iconic are those of writers lucky enough to publish in “the Free World”: Solzhenitsyn himself, Pasternak, and Milosz, to name a few. In Romania, too, those who wrote in exile had the great luck of enjoying freedom to publish successfully, in France and the USA, like Emil Cioran and Mircea Eliade, respectively. Other important names of Romanian dissident literature are Nicolae Steinhardt, Constantin Noica, and Paul Goma (who died just a few weeks ago from COVID-19 in Paris). All of these writers spent the majority of their lives either in jail or outside the borders of their home country, and stand out as mirific models in comparison to those that disappointed in reality: the many authors who claimed to have produced subversive writing and ultimately ended up not publishing anything well after the 1989 Revolution, or, similarly, those who only wrote against the communist regime after it had fallen and therefore no longer represented concrete danger. It must be noted that some suggest this perception is a myth intended to continue the work of marginalizing authors. It is difficult to define a figure that would suffice as “enough,” given the circumstances and various adjacent factors.

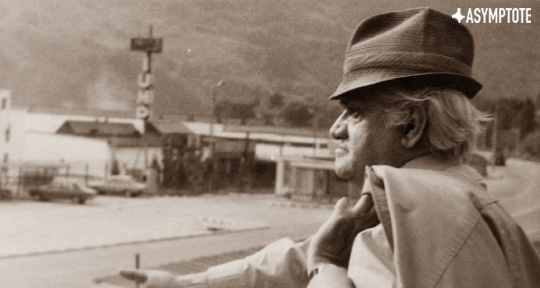

One writer who did produce an opus of “desk drawer literature” and, in addition, chose not to emigrate was I.D. Sîrbu. A remarkably versatile and erudite writer (a philosopher, novelist, essayist, and dramatist; he spoke six languages), Sîrbu was born in 1919 to a mining family in the mining colony of Petrila. This was a noisy, polyethnic, and flavorful place that would become the setting of many of his stories. Coming from a working class background, it was quite unusual for him to have been able to attend the Faculty of Letters in Cluj-Napoca, and even more so to become an associate professor. His father was a syndicalist, and he himself had socialist views—though not communist ones, having already run into trouble as a student when he worked for a newspaper and criticized official measures. The first trial in a long series of troubles had begun before that, when his university years were interrupted by the war, as he was sent to Russia as punishment for his support of miners’ protests. Almost miraculously, he was able to escape the Soviet surroundings by walking two thousand kilometres. In his memoirs, he recollected humorously how shocked his classmates had been to see him on the street, very much alive, after they had held a memorial service for him, “with the girls weeping,” after his disappearance in then-Stalingrad. A few years after this episode, he became the youngest lecturer in Romania (at the age of twenty-eight), but was soon “purged” from the university for his refusal to libel his mentors: philosopher-poet Lucian Blaga and Romania’s first professor of comparative literature, Liviu Rusu. Sîrbu recounted that after refusing to slander them, he was told that his “attitude wasn’t Marxist,” and replied that “it might not be Marxist, but it is moral!,” slamming the door behind him. A few years later, in 1957, despite the beginning of a promising literary career, he was accused of collaboration with reactionaries regarding the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, and was sentenced to seven years of prison, where he was beaten so badly that he lay in a light coma for three weeks, leading Blaga to dub him “the athlete of misery.” Sîrbu himself called his experience in the concentration camp “the long journey into darkness,” but also “a school for those with reserves of essence.” After his release, he worked as a miner, and then lived in Craiova in forced domicile, where he succeeded in getting a job at the local theatre. Still, he remained under the supervision of the secret police, and only succeeded in getting a few minor works published here and there, his work not being taken into critical account. This was probably the work of the secret police, which continued to hound him all his life. Angered by his repeated refusal to collaborate, they told him that “his spine would be broken and that his name would completely disappear, and he could consider himself entirely disappeared from life itself.” He ultimately returned to his native Petrila, where he found all doors closed to him; there the secret police set fire to his house on the day of his father’s funeral. Ultimately, his fortitude in the face of continued pressure so shocked the police agency he was declared insane—an indication that they were overwhelmed by the complexity of their own case.

In many senses, Sîrbu was entirely unique. He called himself “a leper,” and had the courage to remain so for his entire, unlucky life, in the interest of us future readers. In a curious turn of events, the influential and controversial novelist Marin Preda would model the titular character of his most famous novel, The Most Beloved of Earthlings, on Sîrbu—“Victor Petrini” and his universe would begin to shake the foundations of communist Romania in 1980. Preda would soon after die a mysterious death. Still, Preda wasn’t let off the hook easily by Sîrbu, who openly couldn’t stand the character.

A member of the literary “Sibiu Group” (a group of famous writers from Cluj living and working in Sibiu during the Hungarian occupation of Northern Transylvania), Sîrbu wrote of the same Central European universe as his contemporaries, but represented a different artistic philosophy, somewhat marginalized and schizoid, as he was in life: the fact that he was from a proletariat family and had left-leaning ideals himself could not compensate for his desire to act morally.

From the author’s memoirs and letters, it becomes clear that the love he found in his second marriage was the shining light in an overall unhappy and difficult life: “I haven’t lived senselessly if a woman like Lizi has loved me.” And indeed, it was Elisabeta Sîrbu who served as the model for the character of Limpi in the author’s great novel, Adio, Europa!, comparable to Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. Now in her nineties, she continues to work toward the promotion of her late husband’s work.

In a sad twist of irony, Sîrbu died in September 1989, just three months before the Revolution. On his deathbed, wracked by guilt, he requested that the family of a man whose name he had unwittingly taken as his pseudonym know that the subversive articles published unwittingly under this man’s name were in fact Sîrbu’s, as the man had been tortured for them. His mentee, Toma Velici, later found out that a member of the secret police had even been present at Sîrbu’s funeral, “as if he had wanted to be sure that I.D. Sîrbu was truly dead and would be covered with earth forever.” At the time of his death, he left behind five books of significant importance in his “drawer”: novels, plays, journals, and letters.

For that reason, the story doesn’t end. Given the detailed reports of the secret police, the last year of Sîrbu’s life represented, as quoted in Şcoala Memoriei 2012 (ed. Traian Călin Uba):

“. . . a race against time between the author, who had to protect his legacy, and the secret police, that vigilantly sought to intercept and destroy drawer literature. Thus the file illustrates the manner in which the hounding of a writer becomes the hounding of his or her writing, a transfer determined also by the author’s death, though not necessarily. It is not a unique case in the Securitate’s work, just a work method. For this reason, the communist regime was so afraid of writers. Written pages have their own life, one independent of their creator, that could be as dangerous as any outright action.”

Indeed, reading his work, one realizes that the officials working against him were right about his value and potential. He was definitely a realist, obviously preoccupied with portraying daily life, characterized by incisive irony, refined philosophical abstraction, and piquant socio-political settings that characters directly engage with. His parabolic stories are most often about the failed experiment of “re-education”—one example is “Mouse B,” where mice allegorize the forced repression of free will by a totalitarian system. These are rarely pessimistic, more often transcendental or, alternatively, characterized by dry humor. If he had been able to publish in a non-communist country, he likely would have found his place in the ranks of literature as the writers comparable to him managed to do. As it stands, however, he is still relatively little known, with nearly all of his writing being published posthumously. This lack of appropriate criticism might also be due to the fact that it is tempting to link him too absolutely with historicism, simply because his life reads like a crime novel. For this reason, his writing has up to now remained decidedly niche, though it is difficult to say whether Sîrbu himself would have minded this conflation of the circumstances’ implicit components with his writing, as he did say that he considered drawer literature to be “the most noble of the high callings of this time.” Another remark of the author’s echoes The Pilgrim’s Progress: “I learned what Sitzfleisch means for a scholar, what it means not to fear the enormity of the waters, nor the height of the mountain.”

Selected short stories of I.D. Sîrbu are forthcoming with AB Press, in Andreea Iulia Scridon’s translation.

Andreea Iulia Scridon is a Romanian-American writer and translator. She studied Comparative Literature at King’s College London and is currently studying Creative Writing at the University of Oxford. She is assistant editor at Asymptote Journal, the Oxford Review of Books, and E Ratio Poetry Journal. Her translations of the short stories of I.D. Sîrbu are forthcoming with AB Press.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: