In this week’s collection of literary news from around the world, our editors report on political dissident writers in Thailand, a literary festival in Poland, and prizes for writers in the Philippines. Read on to find out more!

Peera Songkünnatham, Editor-at-Large, reporting from Thailand

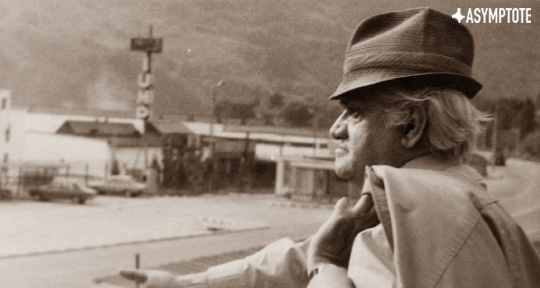

Activists critical of the Thai establishment have to contend with not only the threat of royal defamation laws but also charges of mental illness. No one knows this more intimately than writer, translator, and bookseller Small Bandhit Aniya: in 1965, he was thrown in a psychiatric hospital by police after he camped outside the Russian Embassy in Bangkok and wrote “It is better to die in Moscow than to stay in Thailand” on the embassy walls in chalk. In 1975, he was charged with lèse-majesté for a booklet lambasting Haile Selassie I, the emperor of Ethiopia, but escaped imprisonment due to being diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. This professional-opinion-turned-legal-fact would become the saving strategy for his lawyers in subsequent decades, most recently in 2014—to the dismay of the man himself, who insists he’s perfectly sane.

Starting this week, a literary translation initiative is putting a spotlight on Bandhit’s work along with the voices of other allegedly insane subjects in the kingdom. Under the theme “Madman, Madwoman, Madhuman,” the website Sanam Ratsadon released an excerpt from Bandhit’s autobiographical novel, in which he plays with the idea that he may indeed be insane. Rather than rejecting the diagnosis outright, as he has in his public statements, Bandhit takes the strange route of fictionalizing madness. “There is no doubt that I am mentally ill,” he writes. “Many things I have done in the past and will do in the future clearly signal that I am a psycho, the kind with paranoid schizophrenia.” Is this satire? In any case, this is a literary experiment that has yet to be fully appreciated and properly interpreted in Thailand. May the world be introduced to him, then.

Meanwhile, the short story “Sound of Laughter” by Mutita Ubekka, published as part of the same initiative, questions the self-help, positive-thinking mindset of the Thai public health sector and its allies through the perspective of a woman who is pushed to the brink of suicide by the country’s sociopolitical conditions, like many others in the “Sufferers Association of Thailand.” The story was originally written for a 2020 creative writing contest under the sunny theme of “Day of Suffering That Passed” as part of the project “Read to Heal the Heart.” Seeing through it all, the madwoman discovers her own way of overcoming suffering—through the Jokeresque laughter in a therapist’s office.