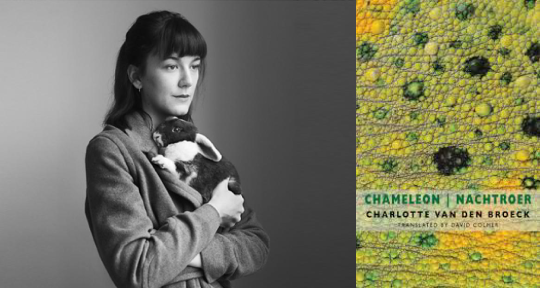

Chameleon | Nachtroer by Charlotte Van den Broeck, translated from the Dutch by David Colmer, Bloodaxe Books, 2020

Chameleon | Nachtroer is the first English translation of Charlotte Van den Broeck’s poetry, which combines the Belgian poet’s first two books—first published in Dutch in 2015 and 2017—in one volume translated by David Colmer.

The publication allows English-language readers to follow the development of the poet’s work from her debut to her next collection. It seems important, however, to read them separately as they were intended, allowing some space to breathe between their readings so that we can fully acknowledge the tonal and thematic shifts in the poems and appreciate each collection by its emotional unity.

Chameleon opens with an epigraph from Schiller’s On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry: ‘After nothing does the womanly desire to please strive so much as after the appearance of the naïve . . .’ Much of the collection plays around with the notion of naivety, from early childhood through to the distancing from the mother and the experience of romantic relationships; naivety becomes an unstable quality that hides both a nostalgic innocence and a darker vulnerability.

The first section of the book, titled ‘The Red Cross on the Treasure Map,’ is concerned mostly with childhood, mixing moments of naivety and clear-sightedness. In the opening poem, ‘Bucharest,’ a child mistakes the meaning of her grandfather’s words: ‘“A splendid collection of little whores they have there,” he said / and I thought a whore must be something like the Eiffel Tower.’ By contrast, in ‘Sisjön,’ the child standing by a lake with ‘a naked grandfather’ intuits something is amiss: ‘We force our cheeks up into smiles, the innocence / of my swimming costume disappears with a single glance.’

The poems on childhood also register early instances of mistrust towards language that will continue to shape the entire collection, upholding naivety as a shield to retain the unbounded perceptiveness that is lost through the acquisition and control of language. In ‘Örebro,’ the young speaker decides: ‘Soon we will stop talking, no matter how minimal / our language, it destroys what we see.’

The following poem, ‘Växjö,’ also formulates the inadequacy of adult language to convey experiences from childhood, with the opening line, ‘There is a lightness here that won’t cooperate,’ posing the problem of sensory impressions that resist being pinned down. Its stanzas outline those elusive experiences:

The world blurs with clumsy swipes of crayon.

There is no perceptible difference between the hand and the table

only a transition of material.

[. . .]Listlessness weighs down everything:

more mass on just as much surface

so that somewhere on the sides of the world

things fall off the edges.

Van den Broeck’s poetry does not fear the difficulty of representing liminal states. She is a poet who is suspicious of language, yet comfortable enough in her use of it to turn her suspicion into a curious exploration of the emotions that language shapes beyond physical reality. Her poems thrive on ambiguity, using slippery images to examine what lies at the edges of sensory experience. This means they can sometimes be hard to grasp, treading a thin line between the figurative and the abstract, creating sequences of loosely tied, ethereal subjects:

at the end of distance you shout

trembling soundwaves in concentric circles.

The outermost rings prove what is beautiful

and good and true: hyperbole

at odds with reality. (from ‘The North Sea’)

The poems often point openly to the use of poetic devices and self-consciously set themselves apart from reality, inviting readers to enter a language without clear rules, which requires attention and imagination. The internal logic of her language produces what is perhaps the most accomplished and distinct element of Van den Broeck’s work—an ease to develop surreal image sequences where seemingly unrelated concepts are brought to the same conceptual level, as in the opening of ‘Seraphic Light’:

A pelican beak opens wide over the top

and bottom of my entire body, that’s how small I am

a man, who pulls off his cowboy boots

and turns into a fish, writhing left and right

on the bed slapping the duvet as if

begging mercy in a wrestling match.Every slap of the fishbody sends flakes of skin

flying, at every slap a gymnast, hands thick with chalk

pushes off in my head . . .

In passages that combine disparate elements such as the one above, the decision to rarely ever punctuate the ends of lines with commas adds to the propelling movement of the sequences of ideas, skillfully crafting them into coherence by way of speeding up the syntax.

Here, the natural flow of the English translations should direct our attention to the work of the translator. David Colmer manages to sustain the elasticity and fluidity of the lines in a different language to that in which these complex poetic threads were conceived; the poet’s imagination has been translated into a new language with a casual vividness and ease that make the poems feel alive in English.

An interview with Colmer for the Asymptote blog (May 2019) stressed a piece of his advice to translators: ‘Do maintain the colloquial tone.’ Sarah Timmer Harvey highlights, in her introduction to the interview, Colmer’s ‘almost chameleon-like ability to absorb and translate divergent Dutch and Flemish voices in fiction and poetry’—an apt expression in the context of translating Chameleon.

Preserving the colloquial seems crucial to Van den Broeck’s work, particularly in maintaining the candidness of the various poems that deal with love and sex. In ‘Charlotte Cake,’ a romantic rejection is framed with these words: ‘you blurting out / that I was junk food, raised / and slaughtered on a McDonald’s farm. . .’. In a more loving scene in ‘Grand Jeté,’ the description of sex is both casual and lyrical:

A kick in the back of the knee, that’s what it feels like

sometimes when I’m bending over you and I don’t haveto hold back bones in this soft body. My spine doesn’t snap,

a stubborn bamboo that makes me bend so farI can keep bending until you kiss another bend into

my limbs. . . .

Maintaining the emotional openness, the last section of Chameleon, ‘Origin,’ forms a rather dark exploration of a complicated relationship between mother and daughter. From the tension of separation at birth—‘Since my birth, an enormous bull’s head has raged / in my mother’s belly. It storms through her abandoned body // gouging scars in the fallow mother . . .’—to a bonding adult holiday together—‘We take a room in a local womb’—the relationship is seen with affection but not without unease.

Coming to terms with the effects of a mother’s mental health on a daughter who has to explain to others ‘the phenomenon “of the crying mother”’ and learn ‘a second language / in which sighs are nouns,’ the closing of Van den Broeck’s debut collection seems to reach a sense of release from the baggage of childhood explored throughout its poems.

The second volume, Nachtroer, mainly explores adulthood and is thematically and tonally less diverse than Chameleon. Some of the excitement of the first book is lost, not necessarily to its deficit, but in a way that indicates the mood of the second collection. While the images in Chameleon are fresh and sharp, the poems in Nachtroer often feel tired, exploring subjects like love in a more pensive way. Some of the playful sensuality of the romantic poems in the first collection turns into doubt and nostalgia, reckoning with changes and endings. Although it contains a poem about the emotional inheritance handed down by family, the collection focuses on personal unrest, tensions in romantic relationships, and heartbreak.

If in Chameleon the separate poems weave together a loose coming-of-age narrative that remains diverse and puzzling throughout, Nachtroer holds most of its emotional intensity in its longer poem-sequences, which turn inwards more than the earlier poems do by means of repetition and insistence. In comparison, the single poems in Nachtroer feel a bit orphaned; they often read like anecdotal sketches of intimate relationships made up of disconnected statements, risking the loss of the reader’s interest.

The sequences construct an expansive and affecting emotional world by giving persistent attention to a limited set of emotions. In some of the sequences exploring romantic relationships, the consistency of a vocabulary that denotes tension is effectively overwhelming: injury, melancholy, tired tissue, unattached, burnt, grief, mistake, withered, failure, deficiencies, exhausted, discarded (from ‘Slash and burn’).

The concern in Chameleon with the imperfections of language reappears and contributes, in this second volume, to the anxiety that pervades many of its poems: ‘the bare throat betrays an open place / where no one hears a voice smashing / against what we exclude from language.’ The imaginative juxtaposition of images also continues to mark the poems, aptly conveying the internal trouble of the speaker, as in the opening sequence, ‘Eight, ∞’:

a magician saws me in two and opens me up

to the audience, my empty trunk revealed after the night, after the battle

in which I became a general and a mortal, lost ground and organs

forgot you because of the trumpets from the parade inside of me

looking back I could already see how you’d take your coat off the rack

a small parting gesture, disappointment between your shoulder-blades

In the face of what look like disintegrating relationships, the collection opens up spaces where the speaker can be alone to navigate and digest her thoughts, to break with the debilitating need and dependence that the poems attribute to romantic attachment. In ‘Groceries Soft Drinks Spirits & Tobacco’ the speaker takes a nightmarish night walk alone, ‘from front door to late-night shop to front door / to the mouth of the volcano, postponing / sleep beside him.’

Further, In the sequence ‘Section,’ a woman navigates the streets of Paris as if she were inside a GPS map overlapped on reality. In this half-virtual walk, she finds a dimension where she is in control of the point of view and her thoughts can flow undisturbed, finally reaching some rest and space to experience beauty:

still the meltwater from a day in Paris sets again

in the morning’s monochrome beautyquietly the white stones stack up as buildings

that don’t yet need to fitthe eye’s expectation and briefly

I can think unobserved

Such journeys, in Nachtroer, from romantic failure to newly gained individuality are a marked evolution from the scenes of childhood, mother-daughter ties and energetic young relationships of the first collection.

This joint volume translation introduces the young Belgian poet to English-language audiences with the rich tonal and emotional range that the breadth of two collections allow for. Van den Broeck’s poems stretch from playfulness to introspective and melancholy moods, and her uncanny imagination characterises every single one of her poems. Chameleon | Nachtroer marks the development of a strange and distinctive voice, which comes through powerfully in David Colmer’s astute translation.

Photo credit: Stephan Vanfleteren

Helena Fornells is a Catalan poet based in Scotland, where she works as a bookseller and freelance translator. She is Assistant Editor for the poetry section at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: