There’s a moment in the documentary Ne Me Quitte Pas that should be utterly unremarkable but got to me beyond all logical proportion. We’re about an hour into the film, and the protagonist, Marcel—middle-aged, morose, pyjama-clad—is sitting alone in the hospital room where he’s being treated for alcoholism. Before him is a large plastic bottle, filled to the peak with a litre of water, and when he goes to pick it up he spills a little. He curses, stands up, and with almost balletic attention to detail embarks on an intricate process of cleaning it up, manoeuvring paper towels as if polishing a masterwork of carpentry. Finally satisfied, he walks across the room, bins the towels, trudges back, sits down with a sigh, slides the bottle over, and delicately extends his hand around it once more to take a sip—only to spill it again. “Merde!” he yells, “C’est pas vrai!”

This humble minute of footage captures with exquisite eloquence a part of life that isn’t often taken seriously in cinema, let alone featured as a film’s central theme: that is, its banal, concrete shittiness. The scene is heart-wrenching and hilarious and entirely mundane; it’s the universe showing off its perfect comic timing at Marcel’s expense. The gag could have been lifted right out of a Charlie Chaplin movie or a Mr Bean show, except that it’s happening in reality, seemingly unchoreographed, to a man for whom most things that could go wrong already have. He’s 52 years old and, yep, his wife has left him for another man, taking their three young kids with her; he’s living alone in a house stripped of furniture in the bleak Belgian nowhereland of Wallonia; and now he’s even had to give up his one remaining solace—scrambling his brains with beer. But the real horror is none of these things. The real horror is the tedium of the day-to-day.

Marcel’s only companion in his dire cosmic boredom is Bob, an ex-cowboy and rum-swigging stoic. Marcel and Bob’s dynamic is that of Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon reincarnated in nonfiction form. Like Didi and Gogo, there’s a tenderness between them that’s unpredictable and unproductive, but also their very lifeblood. They sit around Waiting for Something Vaguely Godot-esque, brainstorming methods of suicide and puncturing each other’s silences with words that swallow and negate their own meaning. “I’m off,” one will tell the other, only for the scene to cut to the pair sitting in the exact same seats hours later. The entire film is soaked through with that peculiarly Beckettian potion of profundity and emptiness.

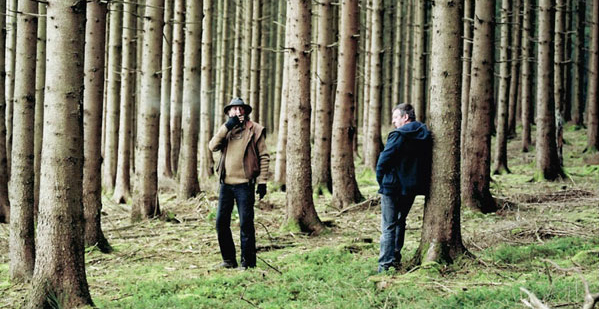

Like this scene: Bob is rambling through a forest in search of his favourite tree, the “Lebensbaum” where he intends to someday end it all (this “tree of life” must be another wink to Waiting for Godot). The journey is majestic, epic, lit up with golden shards of sunlight and set to the orchestral score of Faure’s “Pavane.” We weave through the woods, the music blossoming, the tension swelling, Bob resembling some kind of 21st-century Odysseus on his voyage to spiritual homecoming, until—the music cuts out, the camera halts, and Bob groans with disbelief, “It’s gone”… only to follow up a moment later with a grim chuckle and the words, “Tough luck.” This sequence is rich in its inanity, decadent in its anti-climax. Bathos at its very best.

The fact that the filmmakers include this scene so early on is a pretty clear signal that there’ll be no free-wheeling romanticism here, no smoothing over life’s messy edges. The characters’ attempts to determine their narratives are constantly undermined. In the unabridged slowness of daily existence we’re given moments that seem too intimate and guttural to be on film: hurt words between exes, vomiting in the dentist’s chair, more than a few drunken stupors—but all of it vulnerable rather than violent; lyrical in its candour.

The scene I find the most compelling and the hardest to watch is another lone shot of Marcel. This time he’s in his kitchen, halfway to wasted, his hair limp, his face puffy, his clothes greasy. He slaps a track on the CD player—“Listen To Your Heart,” a song as corny and lovesick as the title implies—and slumps by the stereo drinking beer and eating junk food. As the melody floats out and Marcel crunches his way through an ice-cream cone, I can’t help thinking of the clichéd scenes from countless romantic comedies where the lovelorn Renée Zellweger/Cameron Diaz/Jennifer Aniston character drowns her relationship sorrows in a tub of cookie dough, crooning along to her favourite power ballad. Marcel’s scene strikes me as an achingly dark parody of these pop-culture representations of break-ups. The camera zooms in unflinchingly close to his face as he broods, ice-cream smeared at the corner of his lip. There’s nothing pretty here, nothing airbrushed, nothing funny. The scene feels the way heartbreak feels—pathetic and raw all the way down.

Except, of course, that in this case the documentary medium is playing the game it plays so well—almost seducing us into forgetting that there’s a camera, and that there’s at least one person behind the camera, and that the lonely, alcoholic, suicidal man in front of us is actually not quite as alone as the scene suggests. Suddenly a whole other can of questions explodes open: Who’s filming this? What’s their relationship with Marcel? How are they accessing these private moments? Is Marcel consciously performing, or is he so used to the camera that he’s forgotten it’s there? How real is any of this? How “real” are any of us? This film, like all great documentaries, spins webs from the threads between fact and fiction until they blur into insignificance.

The thought I wind up at is: if this is an on-screen version of what it’s like to be broken, then when the cameras are switched off and everyone goes home there’s a brokenness that’s deeper still. In amongst the filmmakers’ cinema verité style (or “observational” fly-on-the-wall mode) there are strong elements of what Werner Herzog calls “a deeper stratum of truth—a poetic, ecstatic truth” that comes from the stylised moulding of life into art. What I mean is, Ne Me Quitte Pas gets at something about us that’s more real than reality itself.

And, in the words of Estragon, “In the meantime nothing happens.” Near the end of the film, Marcel and Bob have this deadpan conversation:

Marcel: What are you going to eat tonight?

Bob: I won’t eat. I’m going… to die. I’ll die first.

Marcel: Well, yes.

Bob: Then… I’ve got some leftover meatballs.

There’s that tragicomic tightrope that’s being walked throughout the whole film, stringing the line between a kind of existential dread—a huge, terrible discovery about the nature of humanity and mortality—and the trifling ordinariness of plodding through the days, swatting flies, mopping up another puddle of spilt water. And ultimately, these end up feeling like one and the same thing. Exactly what’s so awful is the triviality of it all, the impossibility of living to any heightened, transcendent level—find yourself a magic tree and you can bet it’ll be cut down. Life, the film says, is nothing but leftover meatballs.

But is that really how it leaves me feeling? I don’t think so. I can’t pretend it’s not a bleak film—it’s spectacularly bleak. But as I watch the final shot of Marcel’s motorbike winding its way through the icy Wallonian night, I’m left not only with the loneliness of it all, but the beauty as well. The beauty that catches in your throat, cold and bright, like night air.

***

Emma Jacobs is an Assistant Editor at Asymptote, and also edits for Zero Books and 3:AM Magazine. She recently graduated from the University of Warwick and UC Berkeley with a degree in Literature. She currently lives in London.

Read more: