Many translators might agree that language is song, a kind of mouth music. Each text has a unique time signature and timbre, and when we translate voice, we have to open our ears before opening our beaks to become songbirds. And translators have a special insight into how a language’s sounds are made up of tones: pitches that help to convey meaning. A toneless voice, whether spoken, written or translated, is like a song without melody.

I learnt recently that mouth music is the alternative name for lilting, the subtle rise and fall of words in a sentence, and originally a style of Gaelic singing. Given that the nitty-gritty of literary translation is the picking up on nuances in voice, it strikes me as odd that translators, myself included, don’t dedicate much airtime to lilting. Why don’t we talk about lilting when we talk about voice? Isn’t it odd that translation theorists—boasting the loftiest and loveliest buzzwords in all the humanities—haven’t yet adopted it? After all, lilts are not merely ephemeral: a good prose stylist (and good translators too) can conjure them in writing. In James Joyce’s Dubliners, “The Dead” presents a good example of a lilt woven into a text, one that reverberates off the page when read aloud:

Lily, the caretaker’s daughter, was literally run off her feet. Hardly had she brought one gentleman into the little pantry behind the office on the ground floor and helped him off with his overcoat than the wheezy hall-door bell clanged again and she had to scamper along the bare hallway to let in another guest. It was well for her she had not to attend to the ladies also.

Interior monologue, stream of consciousness, Joyce’s voices, call it what you will—I can’t be the only one who can hear Lily’s lilt.

The dilemma of whether to translate accent (and if so, how?) remains a problem for translators to solve case by case. Whatever we do—domesticate, foreignize, accentuate orthographically, play it down, flip a coin—I have the feeling we won’t stop readers imposing inflections and cadences associated with that language’s accents if they want to hear them. The fact that I have to read Madame Bovary in English doesn’t mean Emma must be virtually uprooted from the north of France and reborn in rural Surrey: I’m not saying her every sentence is inflected as I read, but for me a phrase like “boring countryside, inane petty bourgeois, the mediocrity of daily life,” is inextricable from a little French lilt.

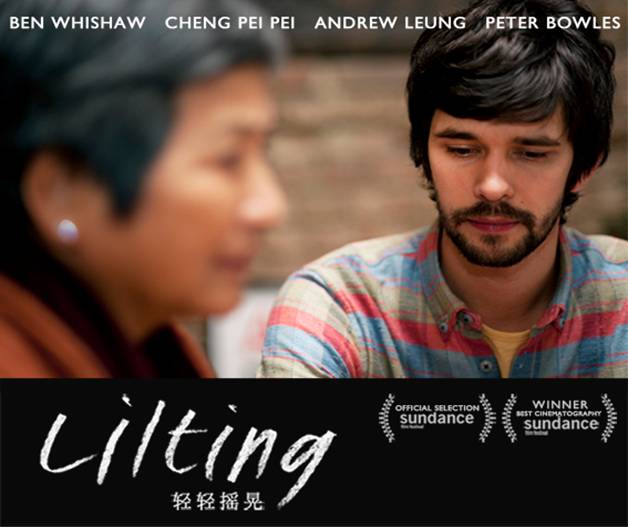

It wasn’t Joyce, but a film that got me thinking about this fecund word “lilting.” Released this summer in the U.K. and in late September in the U.S., Lilting is the first feature-length film from Cambodian-born, U.K.-based filmmaker Hong Khaou. In it, two estranged characters—Chinese-Cambodian Junn and thirty-something-year-old Richard—mourn the death of the same man: her son, and his long-term partner.

Junn is a disempowered immigrant, and her helplessness seems the product of a stubborn unwillingness to embrace either English language or culture. Richard, inconsolable in his grief, galvanizes the last vestiges of motivation he has left to help Junn communicate with an English admirer, a fellow resident of her nursing home. Richard hires an interpreter, Vann, who goes on to appear in almost every scene of the film. It’s little surprise when in the end Richard and Junn’s fractured interactions are the film’s main focus, not the couple’s romance.

We don’t often see interpreting in films (writing this, only the Lost in Translation Suntory whisky commercial shoot comes to mind), but interpreting is key to every foreign language film we watch, whether it’s dubbed or subtitled. Subtitles, in particular, act as an interpreter. We have to simultaneously relax into and concentrate on them. If we don’t, we run the risk of either the film’s storyline, or the experience of watching the film breaking down. More than anything: we have to trust them. Like Lost In Translation, Lilting exploits the comic potential in watching people communicate without a common language—reason enough for me to recommend it—but Lilting also ingeniously turns the conventional use of subtitles to highlight this issue of trust.

Throughout the film, interpreted conversations go something like this: Richard speaks in English, the interpreter relays it in Chinese (no subtitles for us; we trust her, like Richard), Junn responds in Chinese (no subtitles again), and the interpreter relays that response in English (but do we trust her?). I was surprised by how unnerved I felt not knowing what was really being communicated to Junn. As viewers, we’re not even told which of her many languages they are using together (it’s a nice touch—Junn doesn’t speak the global lingua franca, but she’s an enviable polyglot with Mandarin, Cantonese, Hokkien, “the other dialect” that Richard can’t remember, and a bit of Cambodian), and the seeds of mistrust are sown wider when we witness the interpreter lie for Richard:

[Junn speaks, seemingly upset]

Interpeter: She wants to know where Kai’s ashes are.

Richard: They’re at home.

[Interpreter speaks one or two words. Junn speaks, still upset]

Interpreter: She wants to have his ashes.

Richard: No

[Interpreter pauses, raises her eyebrows, eventually says something to Junn]

…

[Junn speaks, seemingly very angry]

Interpreter: He was my only child.

Richard: He was my life. He was my hap… Don’t… don’t translate that, she doesn’t know. She doesn’t know that we were together.

Interpeter: SUBTITLED He said Kai was his best friend.

The square brackets above mark where we don’t have subtitles, where we’re left to trust, like Richard, that the interpreter is faithfully translating his words. In these scenes we’re only given subtitles when the interpreter is making up something to cover a slip of Richard’s tongue. Like Javier Marías’s inflated UN interpreter in Corazón tan blanco (A Heart So White), Lilting lifts the lid on the omissions and additions inherent in interpreting, and exposes the mainstream audience to an age-old translator’s quandary: How much creativity should we permit ourselves?

Other pitfalls of the interpreting process, related to lilting, are beautifully picked up on in the film. With Vann present, Richard and Junn’s sentences are constantly interrupted. Neither has room in the oppressive three-way setup to express their grief. It’s thought-provoking to see how the process of translation, when too bald, frustrates communication: the speaker can’t speak for long enough for their voice to sing; thus, the listener can’t pick up on tones that might have conveyed some meaning. When neither interlocutor can understand the semantics of each other’s languages, lilting is not merely ornamental, but essential to communication. In the final scene, Vann intuits the need to stay quiet, to not do her job, and Richard and Junn each give long, unbroken monologues. Without an interpreter, they are finally able hear the tones, the rises and falls, the lilts in each other’s laments to their common dead, and they understand one another as partners, not competitors, in grief.

I’m always looking for new terms to help describe the karaoke that is translation, and Lilting has generously obliged. Lilts, these nuances that exist beside syntax and semiotics, play a vital part in the balancing act between intended and received sense, abidingly present when we speak and translate across languages.

For now, “lilt” is the new “voice.”

***

Sophie Hughes is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for Mexico. Her essays, reviews, and translations have appeared in The White Review, Dazed & Confused, The Times Literary Supplement, and Literary Review. Her translation of Iván Repila’s novel The Boy Who Stole Attila’s Horse will be published in 2015 by Pushkin Press, and she is currently guest-editing a feature on new Mexican writing for Words Without Borders. Sophie lives between London and Mexico City.

Read more: