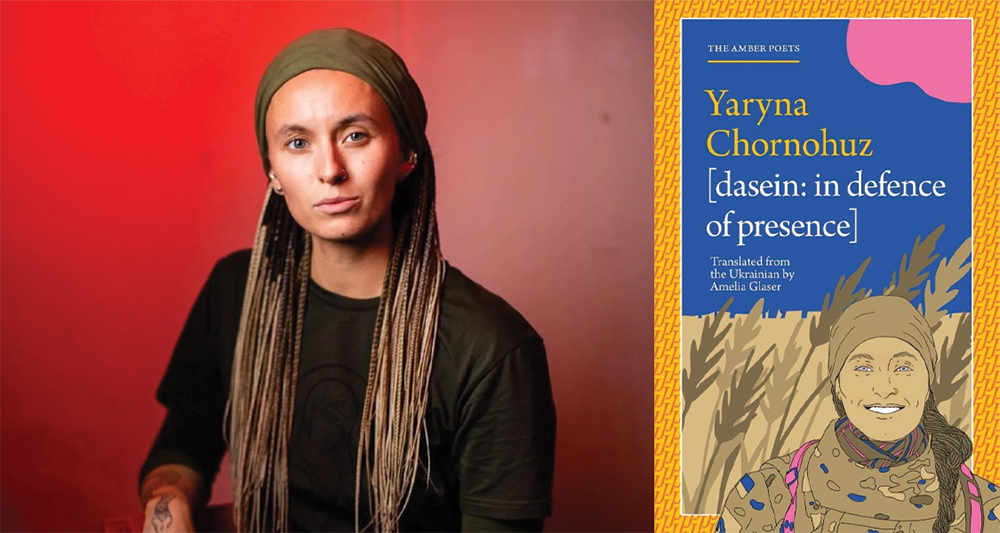

[dasein: defence of presence] by Yaryna Chornohuz, translated from the Ukrainian by Amelia Glaser, Jantar Publishing, 2025

In 1922, the Spanish philosopher, essayist, and poet George Santayana wrote: ‘Only the dead have seen the end of war.’ Though initially penned when reflecting on the impact of World War I, his words would remain just as pertinent a century later. With this sombre message ringing strong as horrors continue to unfold in Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, Jantar Publishing brought us a transfixing collection in late 2025: [dasein: defence of presence], written by widely lauded poet and member of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, Yaryna Chornohuz, and translated by Amelia Glaser. Originally published in Ukrainian in 2023 and drawing on Heidegger’s principle of Dasein (‘being-there’ / ‘being-in-the-world’), Chornohuz writes of her experiences and reflections from the frontlines with harrowing lyricism, exploring themes of existence, mortality, and grief.

In Being and Time, Heidegger defines Dasein as ‘this entity which each of us is himself and which includes inquiring as one of the possibilities of its Being’—in other words, this philosophical principle is distinct from a mere essence or detached existence, but rather stresses the importance of active engagement with one’s environment and circumstances. This significance of inter-personal and inter-situational interaction challenges humanist interpretations, in which people are viewed through the lens of a static Cartesian subject. Further still, this involvement, being so consciously instigated, thereby inherently necessitates a confrontation with one’s own mortality as much as their personhood. READ MORE…