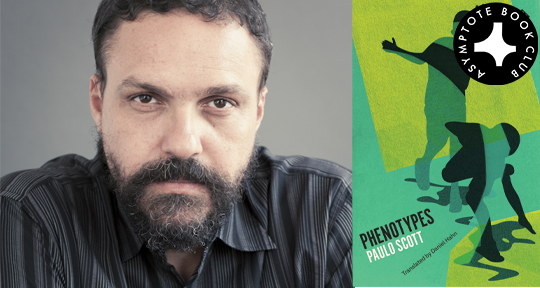

In the first few pages of Paulo Scott’s striking Phenotypes, the protagonist and narrator describes the appearances of himself and his brother in contrasts: blond and brown, fair and dark. What follows is an immersive and urgent novel that addresses the ethics and injustices of Brazil’s colourism in Scott’s signature fluidity and perspicacity, exploring the limits of intentions and justices to probe at the centric forces of activism. As our first Book Club selection of 2022, it is a vital and incisive look at a nation—and a world—stricken with crises of race and identity.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Phenotypes by Paulo Scott, translated from the Portuguese by Daniel Hahn, And Other Stories, 2022

What is the price of activism? Of wanting to change the world for the better? Do motivations, or true intentions, make a difference?

Federico, the protagonist of Paulo Scott’s engrossing and astute novel Phenotypes, is an activist by most definitions. He is co-founder of the Global Social Forum in his hometown—the “whirring blender” that is Porto Alegre; he has researched colourism in Brazil; he has advised NGOs in Latin America and beyond; and now, he is serving on a commission tasked with solving the problems caused by racial quota systems within universities.

Activism, from catalyst to consequence, forms an unavoidable part of his reality. The son of a white mother and a Black father, Federico has always been light-skinned while his brother Lourenço is much darker, and this ability to pass as white has afforded Federico privileges that his brother has never been able to enjoy. The discrepancy has been a lifelong source of awkwardness and discomfort, forcing him into a complex relationship with his own identity. Over time, Federico has ensconced himself in layer upon layer of guilt—a self-inflicted yoke around his neck that continually fuels his activism and shapes his life’s ambitions.

Federico’s impressive resume of achievements stem from his efforts to tackle Brazil’s seemingly insurmountable racism problem—but are these noble actions merely attempts at controlling his circumstances? Is he simply—as his former girlfriend Bárbara puts it—surrounding himself with “noise”? Bárbara, a psychologist who provides clinical care for those traumatised by activism, knows all too well the price people pay fighting for causes they believe in. In her patients, the constant struggle to topple a seemingly insurmountable system, as well as exposure to the true extents of injustice, has left them physically and emotionally drained. In certain cases, the trauma is irreparable. READ MORE…