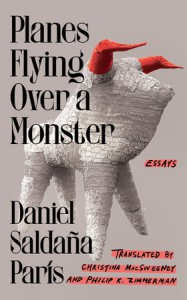

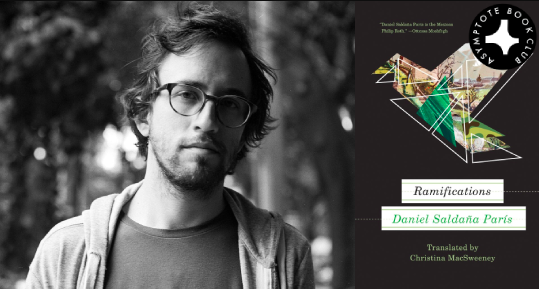

It follows that our most anticipated and widely read work of 2025, tackles the most batted topic of the year: AI. Daniel Saldaña París’s “Translation, AI, and the Political Weight of Words” (tr. Christina MacSweeney) tackles it head-on in an interesting project for Cita Press, and shares his reflections in a thought-provoking essay published in the Summer issue.

For context, Cita Press is an open access publishing project that “pairs contemporary authors and designers with public domain or open-licensed texts to create a free online library of carefully designed books by women, in Spanish and in English.” The project at hand, the “Literary Translation & Technology Project,” involves using AI (Large Language Models, Neural Language Models, and Machine Translators), traditional translation tools, and of course, a literary translator to evaluate AI’s potential for creating open access editions of works in translation. París took on a Spanish translation of Ten Days in a Mad-House by Nellie Bly. In this piece, they mediate on translation through AI, where questions of ethics and effectivity take center-stage—can AI do as we do, but better?

Exactly how revolutionary is this new technology in terms of our profession? Based on my one-off experience of translating Diez días en un manicomio, I can say that the benefits are limited to speeding up the translation process while not necessarily improving it.

. . .

When choosing the most appropriate translation of a particular phrase or sentence, I keep in mind the readership of the text, in addition to its social function: I don’t make the same decisions when translating for a Spanish publishing house as I would for an independent Latin American publisher, or for an open access project that will be consulted by Spanish-speakers of different origins who are unfamiliar with my version of the language. At the other extreme, when translating, I am also conscious of the historical immutability of the original: I am working with a text written in 1887 and I must retain certain usages of that context, even when this may shock our contemporary political sensibilities.

First, París stresses the unacknowledged and unpaid labor concerning the body of work that trains AI. Given that this work is largely skewed to texts by male authors, there is an inherent gender bias in AI results. This would likely apply to translating the subtleties of minority-specific content that the software isn’t adequately trained to handle. Not to mention, were you aware that “each ChatGPT consultation uses two glasses of water?”