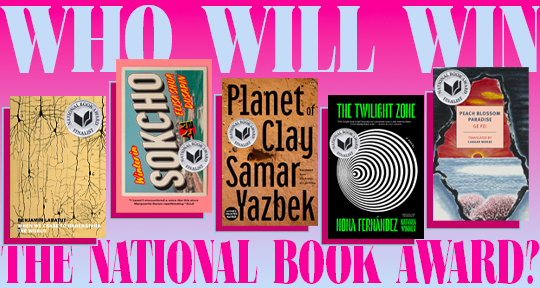

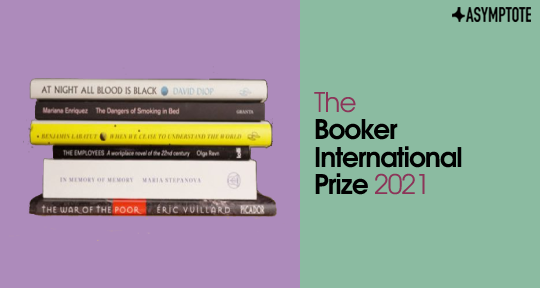

The announcement for the National Book Award for Translated Literature is right around the corner; the 72nd ceremony is due to broadcast live on November 17. On the shortlist are five varied and individual titles: Elisa Shua Dusapin’s Winter in Sokcho, translated from the French by Aneesa Abba Higgins; Ge Fei’s Peach Blossom Paradise, translated from the Chinese by Canaan Morse; Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, translated from the Spanish by Adrian Nathan West; Nona Fernández’s The Twilight Zone, translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer; and Samar Yazbek’s Planet of Clay, translated from the Arabic by Leri Price. Whom will the judges smile upon? Read more for our take.

A friend, not too long ago, once told me that he feels guilty whenever he reads fiction. Just seems a bit indulgent, he said. Yes, I admitted in turn, when pleasure and beauty mix, it feels incredibly indulgent. It was early autumn, dawn was a glorious thing, and we were talking about the first novels we loved—ones I remember for their intelligent presences, their human authority, but most of all, for the distinct, almost secret, pleasure they brought. The indulgence of excellent fiction feels luxurious precisely because of this intimacy: a sense of understanding passed via that most hidden method, of mind to mind. It seems to me that when pleasure and beauty mix, we allow the precocious lies of fiction to move through us, and become truths.

The five titles that make up the finalists for this award are all, in their own respect, remarkable emblems of fiction’s capability to create truth through duplicity. They achieve this through vivid, personal recollections—as in Planet of Clay—or through intensive research—as in When We Cease to Understand the World—or perhaps in what Borges described as “magic, in which every lucid and determined detail is a prophecy”—something I suspect to be at work in The Twilight Zone. The worlds for which these works contribute their imagination are various, wonderful, horrible, and mercilessly true; it makes me think something else about this triangulation of pleasure, beauty, and truth—that it is in the conciliation of the latter two where the incomparable pleasure of fiction is found.

Beauty is not reliably something one can stand to look at for long, but it always leaves something searing. Samar Yazbek’s Planet of Clay—the most lyrical and poetic of the five selections—is gorgeously written, and its translation by Leri Price is a definitive work of art, but it feels sick to talk about the pleasures in reading this story of Rima, a young, mute girl in Syria, as she loses one solid fact of her life after another amidst the atrocities and miseries of war. Instead, Yazbek’s prose is a holding thrall, channelling the child’s voice which springs between stark lucidity and dappled abstraction. Elegantly hanging in the balance between the wounded reality and the salve of her reveries, Rima draws an excruciating impression of the pain she experiences and witnesses, intensifying the horror with an unsparing visuality: “I am afraid of the meanings of things when they turn into words, as it is hard for me to understand bare words without turning them into pictures.” The coarse red of blood, the acrid taste of poison gas, the dusty pallor of a face in death—the words of Planet of Clay are both pictures of unflinching witness, and figures of breathtaking reverie. READ MORE…