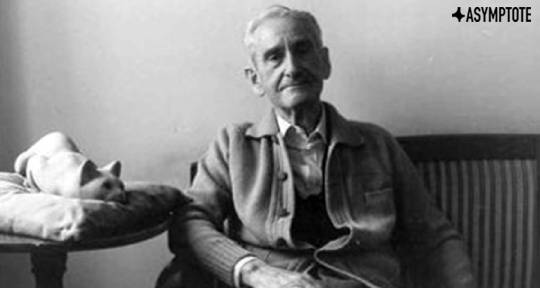

In 1966 the poet Ernesto Calzavara, born in Treviso in the northeast of Italy, published e. Parole mate, Parole pòvare (And. Mad words, Poor words). This collection of poems written in the trevisàn dialect became the emblem of Calzavara’s rebellion against the disappearance of local idioms in favour of the Italian language, but it was also his first step breaking away from the Neodialettali poets and the rural themes and settings of traditional vernacular poetry. The puns and wordplay in this collection are irretrievable in the Italian language—they are part of Treviso as the landscape is, or the weather—but Calzavara believed that dialects had an inherent linguistic power, and only by tapping into that power could they break free from their condition of dying languages. In this essay, Assistant Editor Marina Dora Martino, looks at Calzavara’s poetry in the context of Italian local languages in danger of fading away forever, and considers what it means to remember and forget a language, a place, and a way of life.

Growing up, I absorbed the notion that speaking in dialect was vulgar and inadequate, especially at school. I am not sure where or when my first encounter with the local dialect even occurred—my family (originally from Naples) didn’t speak it, the schools didn’t use it, and most of my friends practiced it only with their grandparents, if at all. Treviso, my hometown, is an ancient city in the northeastern plains of Italy, whose local variation of the Veneto dialect is known as trevisàn—the Veneto dialect being a sort of regional language understood everywhere in the Veneto region, from the mountains to the sea. Excluded from school and spoken rarely among friends, Veneto lingered somewhere at the edge of my life for a long time. It was only by chance, picking up a secondhand book at the town market, that I found out about the existence of local poets, and an entirely new literary world opened to me. This is how I met Ernesto Calzavara’s poetry and realised that I had to rethink everything I knew about the dialects of my country.

It is widely known that Italy has many regional dialects, but not everybody knows that they are more than a bit of an accent and the occasional slang word. Far from being only a distortion of standard Italian, dialects are complex and ancient ways of speaking—in some cases languages in their own right—and they have been around since long before standard Italian even existed. They were known as “volgari,” from vulgo (a.k.a. not Latin but the languages that most common people spoke in their daily life) and they had started emerging from Latin itself as early as the eighth century, transformed by virtue of contact with pre-roman local languages (Etruscan, Osco-Umbrian, Messapic, and the like) but also, throughout the years, by the influence (or invasion) of tongues from other lands, such as Gaulish, Spanish, French, and Arabic. The volgari were generally considered inadequate for the high expressions of the mind, so it was normal praxis for intellectuals to write and discuss their work in Latin. This was until Dante and Petrarch came around, bringing their Tuscan dialect to the forefront of poetic innovation and proving once and for all that volgari could take on the most exalted topics (the Sicilian school of poets had prepared the ground in this sense) as well as the lowest. Indeed, in De Vulgari Eloquentia Dante went even further and made the argument (in Latin, so that it couldn’t be ignored by the intellectuals) that the mother tongue was more noble because it was learnt from infancy, and non-mediated by grammar. Which makes it all the more ironic that his fourteenth-century Tuscan (and Petrarch’s and Boccaccio’s) would later be picked by sixteenth-century intellectuals as the basis for standard Italian, as the result of an educated debate on which of the peninsula’s many languages should become its lingua franca; in reality, a debate of intellectuals for intellectuals that had little or nothing to do with the life of the vulgo. In 1861, the year of Italian unification, 78% of Italians were illiterate, and most of them spoke only their regional language. The unionist phrase “we made Italy, now we must make Italians” shows the uneasiness of a young country whose people couldn’t communicate with each other from region to region, which led to standard Italian being made the language of education, politics, administration, and entertainment in the attempt to “italianise” Italy. Despite this, by the 1950s and ’60s the gap between the official role of Italian and its place in the life of people, particularly in rural areas, was still shockingly wide. With the arrival of television the nation found its most powerful tool for counteracting illiteracy: TV programs like Telescuola and Non è mai troppo tardi (it is never too late) are believed to have taught half a million Italians how to read and write.