Franz Kafka’s gigantic presence in the world of letters is undeniable, yet looking back along the labyrinthine volutes of history, one perceives distinctly the figure of a man who would likely be horrified at the depth and breadth by which we known his work. Having famously insisted that his texts be burned after his death, a betrayal by a close friend led to the remarkable corpus we freely access today. Since then, Kafka’s writings have undergone a dramatic escalade of ownerships, resulting most recently in its comprehensive release by the National Library of Israel. In the following essay, Samuel Kahler traces the events that led to Kafka’s legacy, delineating a writer’s intentions as they come up against the voracious appetites of the world.

“I write differently from what I speak, I speak differently from what I think, I think differently from the way I ought to think, and so it all proceeds into deepest darkness.”

—Franz Kafka

Part of the appeal of reading Kafka (or the madness, depending on who you ask) stems from the durability of the stories, parables, and novellas—their infinite resistance to decisive analysis enduring even after multiple readings. The texts evoke the quotidian anxieties of the modern age, achieving their incomparable effect by leaning into varied traditions of folklore, parable, horror, and the absurd, paradoxically balancing the polarities of universal relatability and a resistance against fixed interpretations. Can a body of work so ripe—so bursting with potential meanings—possibly be pigeonholed with a singular definition? To attempt a conclusive, complete answer—something like a grand unified theory of Kafka—would be the errand of a well-meaning but misguided fool.

Inseparable from the question, and equally difficult to answer, is another problem: namely, that of deciding which works belong in his official catalog and which do not. Mostly, we owe this state of affairs to a complex series of events that began with the discovery of Kafka’s will and continued onward through the next nine decades, through the many publications of his works and, later, the battles over his archival materials and the significance of the contents contained therein.

When the National Library of Israel released its newly digitized Franz Kafka collection this spring, it signified the end of a prolonged conflict over its acquisition. Yet, the collection’s publication does not portend a satisfying resolution for any facet of Kafka’s legacy; rather, it throws the spotlight on academia and the public at large, exposing our continued desire to make something concrete out of Kafka, despite his enigmatic condition.

Kafka’s posthumous drama—call it a tragedy, a passion play, a farce, or what you will—remains an unresolved mess, even after the curtain has supposedly come down.

Act 1

From what is known of Kafka, understanding his intentions may have been as challenging as interpreting his literary works. The Franz Kafka of factual existence—who lived with his parents until the final year of his life, worked for the Workers Accident Insurance Institute in Prague, and wrote in the hours that remained to him—published very little in his lifetime, had a severe aversion to any self-promotional activity, and expressed little satisfaction with his artistic output.

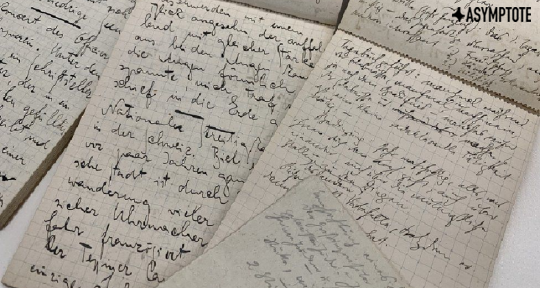

Poor health would force Kafka to take leave of work and stay in various sanitariums during his final years, and he succumbed to complications from tuberculosis in 1924 at the age of forty-one. Aware that his death was imminent, Kafka penned two handwritten letters to his friend Max Brod but never mailed them. (Both were previously published by Brod, but the original versions have been newly digitized by the NLI.) In one, he requests that: “Everything I leave behind me . . . in the way of notebooks, manuscripts, letters, my own and other people’s, sketches and so on, is to be burned unread and to the last page, as well as all writings of mine or notes which either you may have or other people.”

The other letter is somewhat more forgiving:

[H]ere is my last will concerning everything I have written: Of all my writings the only books that can stand are these: “The Judgment,” “The Stoker,” “Metamorphosis,” “Penal Colony,” “Country Doctor,” and the short story “Hunger Artist” . . . But everything else of mine which is extant . . . all these things without exception are to be burned, and I beg you to do this as soon as possible.

After his burial, Brod and Kafka’s parents found these letters, along with a vast archive of unpublished drafts and incomplete stories in the writer’s desk. Brod, who called Kafka “an earthly miracle,” did not simply tarry in following his late friend’s request—he ignored it outright.

Brod would later cite his prior conversations with Kafka as justification for saving his friend’s works from the flames. According to Brod, Kafka had already expressed the same sentiments to him in life, who in turn replied that he would refuse to burn any manuscripts, notebooks, and letters; therefore, so went Brod’s logic, Kafka must have known that he was making an unrealistic demand of his friend. If Brod is to be forgiven, then so are we as readers. We are free to feel sheer gratitude, not guilt, for our unfettered access to Kafka’s words, are we not?

Act 2

Although Kafka’s vision and influence earned him his posthumous literary reputation, few would have privy to the writer’s mind without Max Brod’s intervention. Brod considered it his life’s mission to champion his late friend’s writing, and he wasted no time getting started. By 1935, Brod had secured the publication of all the novels and stories in the original German, acting as editor of the works. He also wrote a biography of Kafka (Franz Kafka: A Biography) and a thinly-veiled roman à clef about their friendship (Magic Realm of Love).

In 1939, Brod escaped from the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia with Kafka’s archive in tow, catching the last train out of Prague before the closing of the Czech border. He would spend the rest of his life in British Mandatory Palestine, later Israel. In the years following his displacement from Europe (or, in the eyes of Zionists like Brod, his return to the Jewish homeland), the inspired literary executor would take his campaign even further, editing and publishing Kafka’s private diaries, notebooks, and personal letters.

Brod used everything at his disposal to transform an obscure Bohemian writer into a giant of the written word. As both editor and publisher of Kafka’s fictions, he shaped the incomplete works into more coherent manuscripts, and presented these fragments alongside the complete works. Later, in publishing the letters and diaries, Brod shamelessly exposed Kafka’s unresolved familial conflicts, his aversion to marriage, and his noncommittal approach to social issues and politics.

By the end of the 1950s, Brod was no longer the pivotal figure in commanding Kafka’s presence; the writer’s reputation had spread internationally, far beyond Prague and Berlin. If the world could know this private man so well, it was because Brod had so completely undressed him for the world to see.

Living in the aftermath of Brod’s actions, the questions that arise are—to what extent are the boundaries of Kafka’s canon still influenced by Brod, and how piously should we obey those boundaries? Having been robbed of control over his legacy in death, perhaps readers ought to take on the moral task of questioning what comprises the definitive Kafka collection—whether it be the handful of works he himself praised or the all-encompassing corpus Brod selected for publication, and if a hierarchy should be established between the two. Alternatively, for a writer whose sense of ownership has completely dissipated, could the Kafka oeuvre even be said to extend beyond the catalog that Brod curated? In the search for what lies at the heart of Kafka’s work, a personal letter or some other miscellaneous item might hold equal or near-equal weight as a fictional manuscript.

Act 3

By the early twenty-first century, interpretations of Kafka no longer lived solely in spaces between the lines of his fictional works, but enacted real-world consequences.

Entering his final years, Brod took measures to safeguard Kafka’s archive by leaving the responsibility for the collection with his secretary, Esther Hoffe. Fate, however, would once again implicate the bonds of ownership. Brod wanted the manuscripts, sketches, notebooks, and letters to be given to a library or archive, but Hoffe instead sold several original manuscripts (in 1988, a manuscript of The Trial was purchased from Hoffe for $2M), and bequeathed the remaining profits to her daughters.

The National Library of Israel would bring this case to the courts, citing its view that Brod had not given the collection to Hoffe as a gift, but merely tapped her to be its executor. It argued further that Brod, a committed Zionist, had wanted the collection to be housed at the National Library, rather than with the Hoffe family or in other institutions like the Balliol Library at Oxford and the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, Germany, which together store the vast majority of Kafka’s surviving papers.

The claim to Kafka’s archive hinged upon the interpretation of Brod’s will. But to an extent, the decision also depended on whether Kafka should be considered a writer of the German language or a Jewish writer. Many could reasonably view this binary construct as preposterous, suspect, and possibly dangerous, yet arguments were made in both directions, the contents of which are expounded in Benjamin Balient’s Kafka’s Last Trial: The Case of a Literary Legacy (2016). The duality was such that Kafka viewed himself as part of a tradition shaped by Goethe, Schiller and other German writers, but also imagined relocating to Palestine and flirted with Zionist ideology; one must also account for the opinion held by many—including the critic Harold Bloom—that Kafka is the quintessential Jewish writer.

Ironically, Israel’s literary interest in Kafka has been tepid, even to the present day. A collected works has never been translated into Hebrew and, at the time of this writing, none is forthcoming. Still, the National Library pressed the issue: why should the archive of a Jewish writer, who seemed to predict the banality of evil expressed by the totalitarian bureaucracy of Nazi Germany and who escaped massacre by German hands in a premature death, be given to a German institution? Is it not an act of justice to rule in favor of the National Library of the world’s only Jewish state?

In 2016, the Supreme Court of Israel’s decision sided in favor of the National Library of Israel. In a sense, the victory seemed to grant Israel a partial, pseudo-official cultural claim to one of the twentieth century’s most beloved and perplexing writers, and might catalyze a greater appeal to Kafka in Israel. It might affirm what has been denied for so long—that there is indeed space for the Kafkaesque sensibility in the particular form of Jewish national identity, as fomented in Israel.

Postscript

Having a prior knowledge of all that transpired—from the unreliable wills of Kafka, Brod, and Hoffe, to the hyperextension of Kafka’s literary catalog, to the last trial in Israel’s highest court of law—it is difficult to view the National Library’s Kafka material with a free mind. Who could possess the strength to escape the influence and impressions by the light of these episodes?

When the newly digitized Franz Kafka collection was published online in the late spring of this year, the Israeli press zeroed in on two elements in the archive: a set of several dozen original doodles and sketches, and some notebooks that contain Kafka’s Hebrew practice exercises. Possibly, these reporters sought an easy entry point for their readers, who may be unfamiliar with the stories or novels. I wondered if they too were actors in the drama, complicit (consciously or not) in the work of assimilating Kafka into Jewish Israeli culture. I struggled in looking at the notebooks, sifting over the handwritten letters of the aleph-bet. Because he tried to learn Hebrew, I questioned, that makes him what—more Jewish? Worthy of Israel’s embrace?

Scrolling and downloading other items from the archive, traversing the manuscripts and letters, I looked for clues that might lead to clarity. But the questions were too great, too interwoven to be answered easily. When will we be finished adding incomplete works and personal materials to his catalog, considering that sufficient evidence exists in the public consciousness to bolster varied interpretations of Kafka’s identity?

I left numerous tabs open on my laptop—the portrait of his mother in pencil, the letters to Brod, the Hebrew exercises—often returning to them over the days that followed. Then the days turned to weeks. Old tabs were closed and new ones opened. Eventually, and not without caution, I have come around to the unsatisfying notion that Kafka belongs to everyone and no one. Kafka floats, shapeshifts, appears in many places at once; he is not a fixed subject. Such elusiveness, conflicting against our mad pursuit of meaning, is perhaps the prime reason why we return to him again and again. Nearly a century after their creation, Kafka’s antiheroes remain a draw to readers not because we envy their often-grim fates, but because their struggles reflect the depths of their innermost selves, aspects of their identities that elude the malevolent, oppressive views of the state, the court, the judgmental relatives. The irony is that their identities are never quite fully on display. Such an unsettling existential condition is one of the thematic bridges that links Josef K. to Gregor Samsa to, yes, even Franz Kafka himself. Fittingly, we readers play the tireless detective, keen to plumb every letter, draft, sketch and Hebrew letter, hoping that we won’t miss a single detail, all the while knowing that a final conclusion is out of reach. With his literary remains torn asunder by Max Brod, archivists, and everyone who reads him, Kafka remains the prophet, the absurdist, the European, the Jew, and more; yet, above all these identities, he is the enigma par excellence, and his oeuvre is a testament to its durability to withstand endless interpretation. Kafka is—or can be—everything. It’s incredible to think, if Brod had obeyed his will, that there would hardly be a trace of Kafka today. For trusting his better instincts, Brod, a friend of genius, could be forgiven for his acts of defiance.

Image credit: Max Brod Estate / National Library of Israel

Samuel Kahler is a writer and playwright based in New York City. He previously served as Asymptote‘s Communications Director.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: