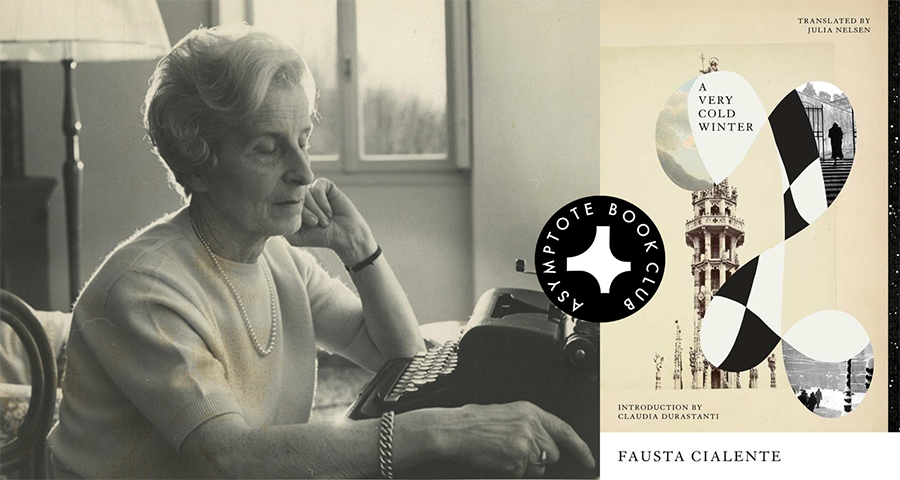

The first winter after the Second World War was famously brutal across Europe: scarce resources, battered cities, and abnormally cold temperatures that seemed to befit the grief and isolation of the already bereft populace. In distinctive, visually rich prose, with evocative and immediate characterization, Fausta Cialente’s A Very Cold Winter captures both the emotive and physical terrains of this solitudinous and ruptured time in Italian history, tracing the season’s frigidity, desolation, and sense of suspension as it works its way through the city and its people. As our first Book Club selection of the year, it is a novel you can feel in your bones.

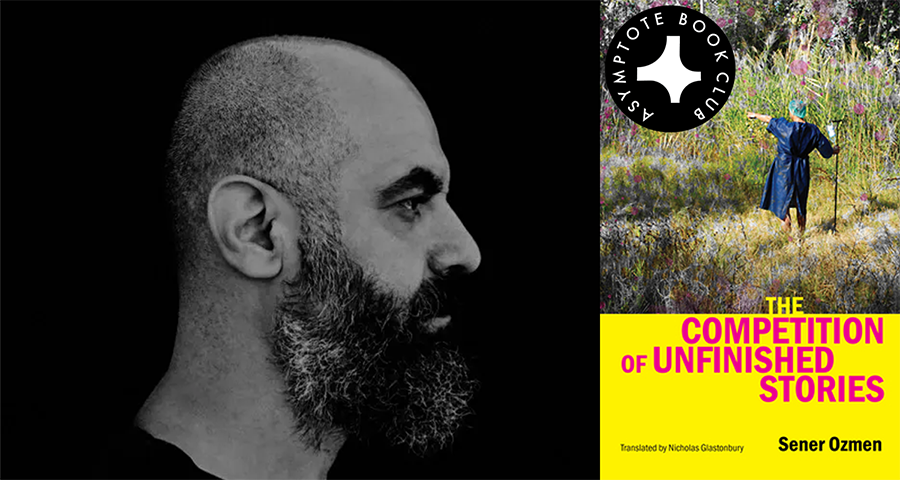

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

A Very Cold Winter by Fausta Cialente, translated from the Italian by Julia Nelsen, Transit Books, 2026

A woman has been abandoned by her husband—but she doesn’t know why. She now finds herself alone with “perfectly useless” memories, daydreams, idle thoughts, and a family to provide for. To make ends meet, she ends up squatting in a dilapidated third-floor attic with half a dozen relatives.

The premise of Fausta Cialente’s A Very Cold Winter may feel contemporary, but we’re in 1946 Milan: a year after the Liberation, when a city devastated by Fascism and Allied bombings was struck by one of the harshest, longest winters of the century. Originally published in 1966 as Un inverno freddissimo, the novel—Cialente’s first to be written and set in Italy—was met with a curious but mixed critical reception; despite being reprinted a decade later on the occasion of its television adaptation (in 1976, the same year Cialente won the Strega Prize for Le quattro ragazze Wieselberger), A Very Cold Winter has long remained half-forgotten and nearly impossible to find. The novel owes its current resurgence to the Milanese publisher nottetempo, which has reissued several of Cialente’s core works (some featuring scholarly contributions by Emmanuela Carbé, editor of her wartime diary), and to Transit Books, whose publication of Julia Nelsen’s textured translation finally introduces Cialente to a wider Anglophone readership. READ MORE…