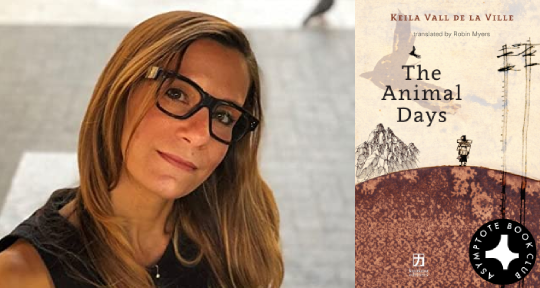

Keila Vall de la Ville’s debut novel The Animal Days is a thriller—but not in the traditional sense. Protagonist Julia, a climber, chases mountain highs as she tightropes between life and death, joy and grief, adolescence and adulthood. She also chases a boy bent on destruction. Julia narrates this time in her life—the animal days—in a powerful, fluid vernacular that plunges readers into her precipitous milieu. We’re proud to feature this cliffhanging novel as our Book Club pick for July and to share this conversation between Vall de la Ville and translator Robin Myers, which was held live for members. The collaborators discuss the delicacies of portraying gender violence, the climbers’ patois, and the way contemporary Latin American literature plays with time and tense.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive Book Club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only interviews with the author or the translator of each title!

Allison Braden (AB): There’s so much going on in this book, even though it takes place over a relatively short time span. Keila, how do you describe what the book is about?

Keila Vall de la Ville (KV): I think of the book as the story of the process of becoming, in which travel, spatial movement, has to do with the inner journey as well. That might seem a little general in the sense that many talk about displacement and movement, geographical movement, as a way to travel inwards.

What makes the book different and what gives the book its identity is this relationship with fear and with the extreme—not only because the characters are climbers but also because of their own particular intimate relationship. Julia’s actually transitioning from one state and one moment to the next. So, it’s all about extremes.

Gender violence pervades the whole story, and it’s very important to me. It took me a while to figure out how to talk about it. We all know how terrible it is, but at the same time, it has so many nuances, and so many colors, and so many ways of manifesting. I believe it’s important to show that it’s not only about physical violence or even psychological violence. There are many, many ways to feel violent, especially in an environment that is mostly masculine.

AB: Robin, how did you encounter this book? What attracted you to the story?

Robin Myers (RM): I came into contact with this wonderful book after coming into contact with Keila herself. We’ve actually been working together for so long that I can’t even remember which came first, Poetics on Beauty or this novel, but we’ve been in touch for a number of years about different projects of Keila’s. Shortly before we started writing to each other, this book had won the Latino Book Award, so Keila was interested in having it translated into English.

I read it and was instantly fascinated. I was riveted by the story and by the force of the narrator’s presence—she has a very subtle narrative voice. But in terms of the language itself, which is always what does it for me or doesn’t as a translator and reader, I was so interested in the intensity and the directness of the narrative voice, which is very beautiful but also very blunt. It has this almost spoken quality, which I was really interested in. READ MORE…