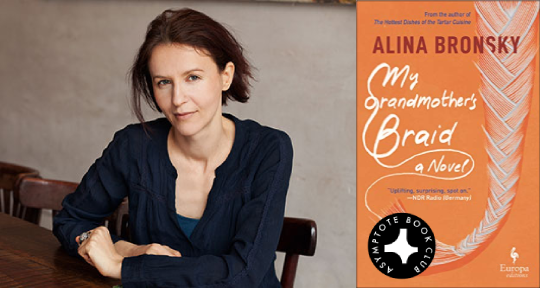

In our Book Club selection for January, we were thrilled to present Alina Bronsky’s brilliantly comic and irreverent My Grandmother’s Braid, a study of familial dysfunctions that renders its players in all their idiosyncratic fascinations. Now, Assistant Editor Barbara Halla talks with Bronsky’s translator, Tim Mohr, about his intimate connections to Germany and its language, the German tradition of immigrant literature, and the challenges of rendering Bronsky’s surprising and intuitive narration.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

Barbara Halla (BH): You have a longstanding relationship with Alina Bronsky, having translated five of her books. Could you speak a little bit about how you came across her work and what inspired you to translate her?

Tim Mohr (TM): Her first book, Broken Glass Park, was either my second or third translation. It came after I attended a speech at Carnegie Hall, under the auspices of a festival called Berlin Lights. I sat in the audience to watch these ostensible experts speak on the German publishing world, and they claimed there was no tradition of immigrant literature there.

I remember thinking that the last ten German novels I’d read were all by what you might call “immigrant” writers, or writers writing in German as a second language. I was really adamant about working in that field and trying to get more of that material into the U.S. market, so people would be aware that this tradition did exist over there, and that it was booming. And then I came across Alina. I loved her debut novel, Broken Glass Park, and because the translation went well, we wanted to continue working together. I wouldn’t want another one of her books to come out with a different translator.

As far as our relationship goes, I tend not to work closely with the authors when I’m translating, and a lot of them speak really, really good English, so it’s all the more daunting in some ways—I don’t want them to be looking over my shoulder, basically! I’ll email them a few queries sometimes, but for the most part, I’m trying to do it on my own. I am somewhat friendly with Alina, but when we get together we don’t really talk about translation or her books, we just have a cup of coffee or something.