Quietly, almost as if afraid to disturb, a new year has made its way into the world. The recession of 2020 into the distance of the past presents an opportunity to not only evaluate the changed world, but also to contemplate our responsibilities in readjusting, amending, and moving on. In a fitting selection, our last Book Club title of 2020 is Guido Morselli’s acclaimed novel, Dissipatio H.G., a text that reconciles the stark realities of mourning with poignant examinations of presence in and amidst so much absence. It is a rare feeling that has somehow, incredibly, become common: What is one to do upon waking up to an unrecognizable world?

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

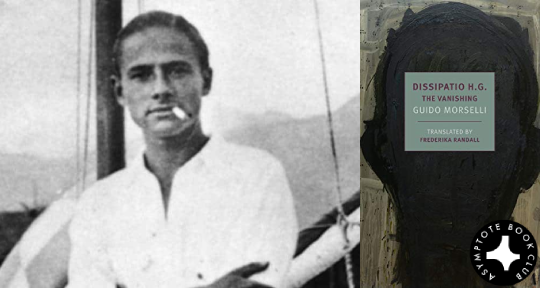

Dissipatio H.G. by Guido Morselli, translated from the Italian by Frederika Randall, New York Review Books Classics, 2020

Near the outset of Guido Morselli’s short and surreal 1977 novel, Dissipatio H.G., the unnamed narrator sits in a cave at the edge of a steep drop into an underground lake, getting up the nerve to end it all. Meanwhile, down in the valley, in the invented, industrious city of Chrysopolis, the economy booms, not unlike the growth Morselli observed in post-war Italy. Leery of society’s so-called progress, the narrator has retreated to an isolated property in the mountains—but even that is threatened; he’s pushed to the lip of nonexistence when he finds a cluster of numbered stakes in the ground “a couple of hundred paces from my mountain retreat.” After a fever and a frantic investigation, he uncovers that a company plans to build a highway there, complete with entrance ramps, a cloverleaf, and a motel. “As Durkheim might say,” the narrator reflects, “there’s your trigger.”

In the end, he abandons his plan after contemplating the quality of the Spanish brandy he’s brought along for liquid courage. His body’s physical matter simply refuses to accede to his will; he bangs his head on the way out of the cave, just as a powerful groan of thunder rolls through the valley. “The truth is,” he thinks, “a man who draws back from killing himself does so (and Durkheim didn’t see this) under the illusion that there is a third way, but in fact tertium non datur—there is no third possibility: it’s either a leap into the siphon or a dive back into daily life, where the rhythm of everything has stayed exactly as it was and you must hasten to make up for the progress lost.”

But when he returns from the cave, the narrator discovers an entirely unexpected third possibility: while he has chosen to live, the human race has vanished. He inspects the newsroom where he once worked as a journalist, placing calls across Europe and across the Atlantic to determine that for all functional purposes, he is the last man alive. “I’m now Mankind,” he says. “I’m Society (with the capital M and the capital S).” He is, he says, “Incarnation of the epilogue.”

He finds villages wrought to silence. The drainpipes continue to leak and church bells fruitlessly mark the time, but the narrator discovers a deeper silence in human absence. “It’s a silence that doesn’t flow,” he observes. “It accumulates.” The Event, as he calls it, and this newfound silence frees the intellectual narrator to contemplate his unusual position as sole inheritor of the mantle of mankind. He delves into solipsism and draws on contemporary writers and ancient thinkers to make sense of his predicament. His philosophical digressions are matched by a physical rootlessness. He visits the train station. He commandeers a car and ventures “out into the airport’s crepuscular enormity.” He abandons his home for an eerily empty hotel.

The late Frederika Randall’s accomplished translation keeps pace with the narrator’s many-tentacled digressions and philosophical somersaults. Her language hitches the reader to his galloping thoughts and follows him into “the thick foliage of the forest of speculation.” Her translation contributes to the book’s sense of momentum—despite its lack of traditional plot and characters—and her introduction contextualizes Morselli’s work, subtly connecting this story to the unforeseen events of 2020.

Indeed, it’s difficult to read Dissipatio H.G. without linking Morselli’s observations to our own time. Echoes of our pandemic isolation resound: “There is no one to change my clothes for. The only reason I shave is because the sharp beard hairs bother me at night while I’m sleeping.” He goes on to dispel the notion that the disappearance of mankind implies the end of the world: “The birds are making an unholy racket, and their numbers have grown.” A family of chamois goats walks along the railroad tracks—“something that’s never happened before in human memory.”

The prologue to another apocalyptic story is scrawled across our daily lives. “Coronavirus death toll hits 1 million,” announced The Washington Post in September. But it isn’t just the pandemic: an unusual “derecho” storm devastated the American Midwest. The Atlantic hurricane season shattered records as the quick succession of named storms blew through the alphabet. Permafrost in the Arctic tundra and boreal regions further thawed, threatening landslides and sudden changes in climate patterns. As the global economy falters, the rich get richer. Unlike Morselli’s, our apocalypse is messy. Beneath sheets of ice, the permafrost turns to mud.

Amid the chaos already arrived and the threat of more yet to come, there is a small and temporary comfort in imagining the world without us. As we eradicate plant and animal species at a rate so astonishing that many have labeled it the globe’s sixth major extinction event, we can luxuriate momentarily in a fantasy of the earth rewilding once we’re gone, a slow and verdant undoing. Morselli’s narrator is the type to indulge in such daydreams. “I am, on and off, an Anthropophobe,” he says. “I’m afraid of people, as I am of rats and mosquitoes, afraid of the nuisance and harm of which they are untiring agents.”

But in their sudden absence, he begins to reevaluate their importance. He surprises himself with an unfamiliar attitude toward humanity: “An unexpected disposition to understand and feel for them. Sympathy, empathy. A shipwrecked human solidarity bobs up, a surprise last-ditch response.” As the narrative comes to a close, he seeks out the once-abhorred metropolis, then wonders why. “The crazy drift of the paper boat come to Chrysopolis to sink.”

Dissipatio H.G. is an invitation to muse about the final act of the human race, to connect Morselli’s collage of influence to our own, and to the events that have unfolded since his own suicide in 1973, soon after he completed the book. It’s an opportunity to unspool our own imagined reaction to the loss of mankind—and perhaps find in it an unexpected sympathy. In Chrysopolis, the narrator passes under a banner that reads, “Capitalists, it’s all over!” He watches the rivulets of rainwater leave thin layers of sediment on the street and the tendrils of green that spring from this “veil of earth.” The stock market building, the beating heart of the city, will crumble. “The market of markets will one day be countryside,” he muses. “With buttercups and chicory in flower.”

Allison Braden is a writer and Spanish translator. In addition to representing Argentina as an editor-at-large for Asymptote, she is a contributing editor to Charlotte Magazine and an editorial assistant for the academic journal Translation and Interpreting Studies. Her writing has appeared in Columbia Journalism Review, The Daily Beast, Asymptote, and Spanish and Portuguese Review, among others.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: