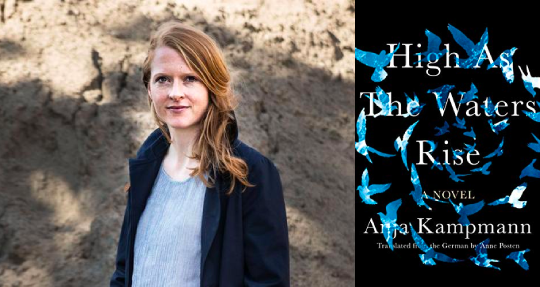

High as the Waters Rise by Anja Kampmann, translated from the German by Anne Posten, Catapult, 2020

In the rich silt into which Titusville, Pennsylvania sinks its foundations, there was only one spot where it was possible to strike oil at the extraordinarily shallow depth of sixty-nine feet. On August 27, 1859, a small group of men, at the last-ditch orders of one Edwin Laurentine Drake, sank their pipes into the ground—guided by that unknown intuition which, in retrospect, looks terribly similar to fate—and black gold flowed forth. It is how the world flows forth from a single life, from one man’s fortune to a new forever, a radically altered world.

The idea of fate, its shrouded force, is perhaps the only abiding salve for the more devastating consequences of self-awareness. We look back on our times to construct an architecture of experiences, arranging fragments by our available logic to see what structure rises from the flood—what materializes in the aftermath to become that one reference by which we can define, or justify, our lives. For some reason, we always urge towards a singular narrative, despite sharing in the overarching suspicion that the life one leads is not one, but always many. The salvaging of this steadfast, solitary lesson is a comfort—that it indeed has all been for something. Without it, there would be only darkness, that eternal torrent, that deafening collapse.

Because Anja Kampmann begins High as the Waters Rise with an ending, we arrive at the temporary space between the shock of happening and the proceedings of salvage. Waclaw and Mátyás are longtime companions working on an oil rig, sharing in a rare and profound intimacy that dissipates the customary subscriptions of male camaraderie. When Mátyás vanishes from the ship in an incident so abrupt and absurd that it seems almost mystical, Waclaw is stirred into a potent, hypnotic grief—a grief that necessitates the sea, the infinity it conjures, which Kampmann calls upon in the vignette that opens the text: “There would only be sea, piling up and up. There would be no north or south. The water would swallow even the cries of the storm, which no ear would hear.” In the midst of these tides—which overwhelm the daily rituals of work, care, and thought—is the solitary island of memories, visions in which Mátyás is frayed at the edges by recall. Only these mirages anchor Waclaw: these small footholds of before, in the vast midnight of after.

What follows is his navigation of this new landscape. He leaves behind the rig, with its insane mechanics, obdurate pursuits, and occasional pockets of human tenderness. Onwards, he travels to Tangier, where he and Mátyás once found reprieve between bouts of withering work; then to Boćsa, the imperturbable Hungarian village of Mátyás’s birth, where his sister still lives, desperate with a love that no longer has a subject; then Malta, where a piece of Waclaw’s prior self survives trivially inside the body of a woman. Eventually, there are the thin roads of rural Italy and something like family, something like reason, living inside a small, stone house. Even then there is furthermore—Kampmann has an extraterrestrial way of writing Waclaw’s journey that sequesters his path in a wide pool of remote directions—but the places blur with abandonment, loss, and clouded fates. It is a testament to the author’s craft that she is able to render these landscapes with vivid sensuality while imbuing them with the suffocation that grief inflicts upon consciousness. Even as the whole idea of place is made irrelevant by the fact that we are trapped inside our limited experience of it:

The boy asked how big the world was. Waclaw said he didn’t know. On some days it was bigger, and on other days it was as if it didn’t exist at all, even when you flew around it in an airplane.

Throughout these travels, there’s an exhausting suspicion that fate is somehow sheltered in the distance, as if the future were something to rest one’s tired head upon. Waclaw is sometimes chasing shadows, often trying to sleep, sometimes dreaming. Time is meaningless, save for the need to sleep, calling back to the hard, dayless days spent on water. And though he is missing the characteristics that have been disabled by mourning—desire, foresight, empathy—his body is still fraught with human needs. It reminds him to eat, to drink, to sleep with women; it alone keeps time. What then emanates from him is something that resembles patience, or whatever comes when there is no one, and nothing, waiting in the beyond. It is never, he has to go. It is always, “He couldn’t stay.”

Kampmann—known first for her poetry—seems to have drafted her sensual logic from the art of verses. The hours are grafted onto one another, recollections are more present than bodies, and daily life occasionally withdraws completely into the invisible. The language circulates and drifts in tidal motions, the ready fire of human emotions tempered by nature’s fullness. It is enough to speak of mountain ranges instead of anger, to focus in on the hem of a petal instead of shuddering tears. There is “enough silence to make their arms stick to the tabletop.” The shed of night upon the skin is “a new kind of ice, something that could have come only from inside him.” The dialogue is rendered with such quietude and gentleness that it is almost like no one speaks above a whisper. Anne Posten translates with delicate intuition, rendering the music with such grace, that it seems as effortless as translating the rhythms of the waves themselves—which of course, no matter where you are, always sound like waves.

It is not easy to write about something as consuming as grief; it is even more difficult for language to enter right in the thickest dread of it, the incomprehensibility of it, the hopeless, elegiac nature of trying to bring absence into sharp relief. Yet High as the Waters Rise fills the great blank canvas of loss with a precision that nourishes the fine contours of emotion, wherein sadness is a thing of many shapes and colours, following a love that has no nature but wherever and whenever the lover is. Throughout the first part of the novel, I tried to discern certain elements that would confirm Waclaw and Mátyás’s relationship as romantic or platonic—whether the scenes of their physical intimacy were of a sexual nature, whether their explicit attachment to one another was as brothers or as lovers. We do not have so many ways to talk about the love between men beyond those two polarities, and it struck me that one of the most powerful assertions the novel makes is against the presupposed carelessness between men: they need, comfort, and feel one another outside the simple constructs subjected upon them. Women have long acknowledged that the love between them is capable of wildness, onslaught, and dependency, without the emergence of sexual attraction; it perhaps speaks to the distinctions of gender dynamics that Kampmann—a woman—is writing about and from the perspective of men but giving voice to the vast gradient of relationships they undoubtedly experience, a voice seldom heard between the hasty definitions of male devotion.

“I’m just saying that we are all we’ve still got out here. And this platform has a history, just like us, and if we don’t know it we’re fucked,” an older driller says when they group together in a corner of the rig, after one of their own has caught his arm in one of the spinning chains on the drill pipes. One imagines the mental toll of being out at sea, on one of these gargantuan structures that crack deep into the earth; the endless lurching of waves, the sheer distances—upward, downward, all around. In the brutal mechanics of industrial production, bodies cannot all be accounted for. When Waclaw questions the foreman about Mátyás’s disappearance, he explains with clinical resolve:

Either the waves pushed him against one of the steel pontoons—he balled the fingers of his right hand briefly into a fist—or the undertow swept him away.

There is no comprehensive narrative about what brings these men together to be lost. It must have something to do with the money. It may also have something to do with helplessness, with desperation, with a need to escape; with the appeal of floating from city to city, from field to field, or the vulnerability of disappearing, like salt that intensifies the taste. For Waclaw, it has something to do with a woman. Yet these men are gathered from their disparate origins as functions in a single machine, their disposability as appealing as their willingness to work. In Malta, someone tells Waclaw that they have “wash[ed] up like animals after an oil spill.” High as the Waters Rise does not say what they are looking for; what it does say is that they don’t find it. Instead, sometimes, they find one another.

Some managed to stop after a few years. They set aside what they’d earned. Built houses—they returned to those worlds that had lined the insides of their lockers for years, dog-eared children’s curls and plastic slides, worn photos. Paper that you could take out and look at. Paper that sometimes said nothing other than that time didn’t stand still. Not for a picture. Not for Andrej. Not for Pippo. Not for him. Others drifted away. Without knowing where the tide was carrying them. Without knowing. In all of it, Mátyás was one of the few who seemed to swim under his own power: a needle, an inner compass.

It was Rilke who said that what we call fate does not come from the outside, but goes forth from within us. Waclaw briefly wonders “if one day a moment would come when someone would flip over a life, and all the individual layers would finally form a whole,” and if so, what the pieces would be. But as the recurring invocations of Kampmann’s words insist, perhaps a book, its firm structure, is not the right symbol for a life. Perhaps a life looks something more like water, where layers fold into one another and become indistinguishable, and forms are endlessly mutable, and directions are not ever just one-way but simultaneously various. Where the moments and people we have lived through are not in fact discrete points on a long line, but waves which occasionally recede, revealing a little of what’s beneath them before returning to pull us back in. Perhaps a life is something to be submerged in, not something that emerges from the depths.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor born in China and living in Tokyo, Japan. Find her at shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: