This month, we are excited to present new works in translation that consider survival and coexistence in many forms. From the Hungarian, renowned author Magda Szabó delves into the embittering effects of poverty and hardship. From the Spanish, Pilar Quintana creates a riveting familial portrait of vulnerable parents and too-wise children. From the German, Dr. Ludger Wess leads us on a journey to discover the smallest lifeforms amongst us. Read on to find out more!

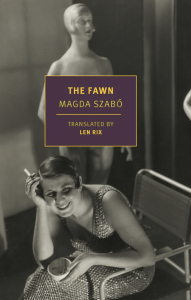

The Fawn by Magda Szabó, translated from the Hungarian by Len Rix, New York Review Books, 2023

Review by Meghan Racklin, Blog Editor

In The Fawn, the latest of Magda Szabó’s novels to be translated into English, it is 1954 in Budapest. For Eszter, the novel’s main character (it is difficult to call her a protagonist), it is 1954—but it is also the interwar years and the years of the war, and it is also, disastrously, almost the future. “The Future . . .’” she thinks, “[t]hat was something I had no desire to build. I had enough of the past about me already for the thought to do anything but horrify me.”

The novel is Eszter’s account of her life and her surroundings, told in a monologue directed at the man she loves, and the language is as beautiful as Eszter is bitter. In Len Rix’s translation, Eszter’s sentences are full of clauses; she’s in a rush, trying to get out everything she wishes she had already said. She recalls, of the evening when her childhood home was hit by a bomb, “Mother neither wept nor blanched; we slept the sleep of the contented in the main hall of a school, along with everyone else who had lost their homes; I felt like the nation’s favourite child, everyone seemed to want to look after us, and the whole city shared our grief.” As her outpouring continues, details pile up like debris.