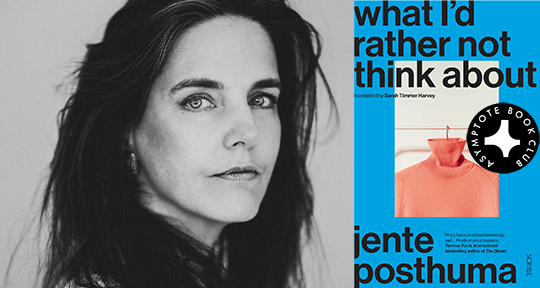

Jente Posthuma’s What I’d Rather Not Think About delves into the closeness of a relationship that many find difficult to understand: the inextricable link between twin siblings. Through a delicately woven tale of memory, shared selfhood, and grief, the author takes us into the mind that struggles to understand a world shattered by loss, when one sibling dies and another is left to reconstitute the fragments. Poetic and surprising, Posthuma shows how even in the most intimate of connections, in another person lies the great unknown.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma. Translated from the Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey, Scribe, 2023

In short, poignant vignettes, What I’d Rather Not Think About is Jente Posthuma’s story of twin siblings: a brother who commits suicide, and a sister who is left behind. True to its title, the novel grapples with the narrator’s dark, complicated feelings of loss following the death of her brother, as she ruminates on the intensity of their relationship. In reflections of the siblings’ childhood and youthful dreams, tracing how these dreams changed or were lost on the way to maturity, Posthuma develops an affecting novel about grief by embracing its full complexity.

From its opening passage, Posthuma hints to the darker turn the twins’ story will take; the first memory shared is of the two experimenting with waterboarding as children, after seeing a film about Guantanamo Bay. To this, their mother sighs, accurately guessing that: “this has to be one of your brother’s ideas”. The untraditional game cleverly introduces their relationship, with the brother being more in control of their makeshift experiment, leaving the narrator coughing and spluttering from the experience. She asks her brother: “Why didn’t you help me?”, and only receives a single “sorry” in return. This pattern of behavior continues as adults, such as when the narrator joins her brother in a diving lesson, since “my brother expected me to follow him because that’s what I always did. If I wanted to go in a different direction, he would ignore me and keep walking.” READ MORE…