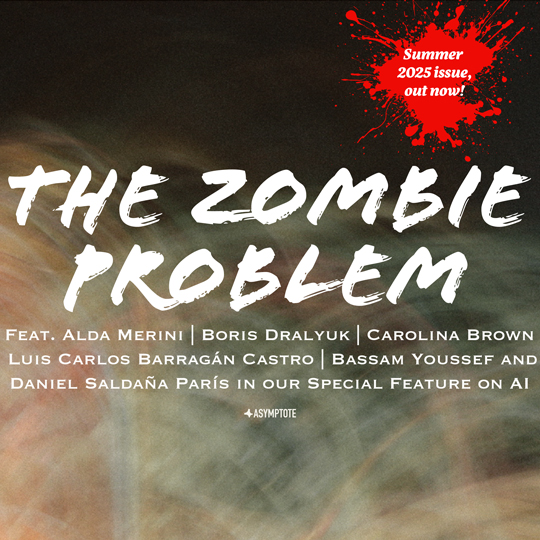

I have complicated feelings about Carolina Brown’s “Anthropocene” (tr. Jessica Powell). The brevity it accords its narrator’s transness is alternately touching and maddening, the fatphobia is at once completely spot-on for such a self-loathing narrator and at the same time it is pretty dehumanizing‚ but, ultimately, all that falls away in the ravaged face of a one-armed zombie jogging across the post climate-change Antarctic wasteland. A wonderful sci-fi tale.

I’d love Syaman Rapongan’s Eyes of an Ocean (tr. Darryl Sterk) for the title alone, but fortunately, Rapongan seems like a strong contender for the title of the actual most-interesting-man-in-the-world. His play with words, his treatment of colonization and indigeneity, the kindness with which he talks about younger generations. I really needed to read something like this, after all the ugliness that’s been going on in my own country.

I love the gender-bender secret agent in Valentinas Klimašauskas’s Polygon (tr. Erika Lastovskytė) so freaking much. The concluding discussion of airplane spotters is a particular stand-out for its treatment of how individuals become conscious of their political power.

Refugees are human beings. Where Rodrigo Urquiola Flores’ “La Venezolana” (tr. Shaina Brassard) shines is in its steadfast refusal either to vilify or idealize them, to present them in all their messy humanity, and in its willingness to show how shameful the narrator’s behavior towards them.

—Julia Maria, Digital Editor

Emmanuelle Sapin’s story “A Child Is Stolen” (tr. Michelle Kiefer) starts off with a swift, telling punch to the gut and builds from there.

Ahmad Shamlou’s poems in Niloufar Talebi’s lilting translation hover in waves of emotion and radiance: “Give me mirrors and eager moths, / light and wine…”

With playfulness and insight, Katia Grubisic sharpens the discussion about AI and translation by focusing on error in her piece “The Authority of Error”: “My argument is that AI makes the wrong kind of mistakes. Mistakes breed resilience, and, most importantly, humility.”

Fawwaz Taboulsi, in Yasmine Zohdi’s translation, steers us directly into the sadness of Lebanon, 1982, and the time of the Siege of Beirut. His grief speaks with lucidity: “And, ever so slowly, the departing fighters peel away from the grasping, waving hands and from the embracing arms. Like skin peeling off its own flesh. They peel away from the farewells. From the prayers. From the promises.”

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about how writers build characters. Jana Putrle Srdić’s poem “End of the world, beginning” in Katia Zakrajšek’s translation, does this in striking ways: ” Sitting on a warm rock, scratching in the wind, / you are a monkey, a branch with ants filing along it, debris in the air, / spots of flickering light”

—Ellen Elias-Bursać, Contributing Editor READ MORE…