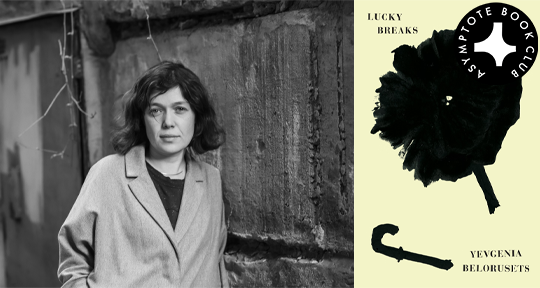

As war cruelly rages on in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one searches for elucidation amidst madness from the country’s writers. As pivotal statements of witness, hope, persistence, and humanity, such texts will undoubtedly go down in history as bright sparks of intelligence and endurance in the dark obfuscations of violence. In Lucky Breaks, Yevgenia Belorusets’s stunning documentation of daily life in eastern Ukraine, the author expertly renders stories of women struggling to reconcile their existence with the broken infrastructure of their country, weaving oratory and textuality with an expert balance of surrealism and sobriety. Testifying simultaneously to Ukraine’s tumultuous history and its uncertain present, Belorusets’s timely work speaks, necessarily, to what survival means, as it is happening.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

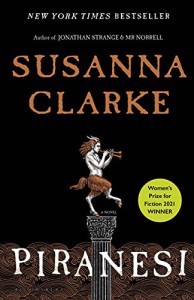

Lucky Breaks by Yevgenia Belorusets, translated from the Russian by Eugene Ostashevsky, New Directions, 2022

More than a month now since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, the crisis for Ukrainians continues to have no end in sight. For those of us spectating from afar, the internet has burst into a deluge of breaking news: images of aerial attacks, fleeing citizens, and pulverised buildings circulate and refresh, drawing us into the eye of the conflict. As for the heart, how much of this goes into cultivating real empathy and solidarity, and how much into encouraging a lethargy towards the bits of violence we witness daily through the screen? Literature and translation have risen up almost instinctively to defy this impersonal onslaught: from readings organised by The Guardian to Odessa-born poet Ilya Kaminsky’s advocacy of Ukrainian poetry. Asymptote, too, has launched a new column in support of Ukraine, and as Translation Tuesdays editor, I published Oksana Rosenblum’s translation of Yevhen Pluzhnyk’s “Galileo,” which, while published a week before the invasion, eerily voiced the fate of small states: “I am quiet as grass, even quieter still,/ I am so easily unnoticed.”

The question of what photographs and literature can do in war, I suspect, will not be resolved anytime soon. Amidst this media torrent, however, the daily war diary of Ukrainian photographer and writer Yevgenia Belorusets stands apart for her ability to document the war in both its pedestrian and surreal registers. On the third day, for example, Belorusets writes about meeting a woman in the park who, while carrying two huge shopping bags, admits happily to her: “When there are two of us, I’m less afraid of the artillery.” Two weeks later, she hears two students speak outdoors about what it means to teach as air raid alarms sound. Occasionally, she includes photographs: friends walking their dogs after curfew; a woman holding two bouquets of flowers. Often, the moments she records are ordinary, allowing the mingling of fragile, contradictory truths—that of people living in a simultaneously exceptional and quotidian time and place. Receiving these daily dispatches in my inbox, they come across as disciplined, tender, and urgent.