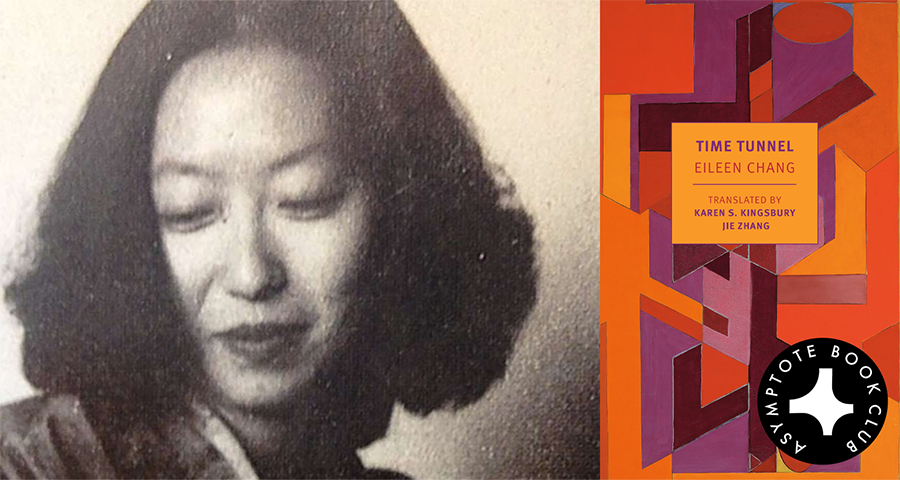

Time Tunnel, the latest collection of the masterful Eileen Chang, furthers the English-language legacy of a writer dedicated to documenting life as it is lived: the multiplicity, the manifold, the vertical and horizontal journeys, the era as it intersects with the individual. Putting together both fictions and non-fictions, translators Karen S. Kingsbury and Jie Zhang present the late Chinese author in her many stylistic and thematic shades, cementing her contemporaneous concerns with her literary heritage, her peripateticism with her depth, and her reputation with her idiosyncrasy. In this interview, they speak on their intimate collaborative process, the global spread of Chang scholarship, and the aspects of self that they brought to this text.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Hongyu Jasmine Zhu (HJZ): How did the two of you first come to Eileen Chang’s work? What first drew you to her writing, and what keeps drawing you back to it?

Karen S. Kingsbury (KSK): I have a really long answer, because I’ve been working on Eileen Chang now for about three decades. I first got attracted to her when I was in graduate school in New York City; I was on a mission to find a modern Chinese writer—preferably a woman writer—who would really hold the attention of English department professors, the ones I had been trained under as an undergraduate, whom I would describe as fairly old-fashioned and very Britain-focused in their sense of literary value. So I basically had a chip on my shoulder. I was like: I want to show you that there are good things outside of English, that there are great things in China.

I feel that many years later, a lot of that has been accomplished—certainly not by me, but by Eileen Chang, and by a very large community of readers and translators. So I just want to let people know that Love in a Fallen City (which is not in this volume, but is in an earlier volume I worked on) is now in the Norton Anthology of World Literature. It was also saluted in Granta, which I have a lot of respect for, as “The Best Book of 1943.” And Goodreads, which is an interesting barometer of interested readers from a lot of different backgrounds, not only describes Eileen Chang as having a stark and glamorous vision, but calls her “a modern master.” So I think that some of my initial incentives have been seen through to fruition, and I’m really excited about that. READ MORE…