In “Verisimilitude,” the Fall 2016 issue of Asymptote, Assistant Editor K.T. Billey edited a stellar special feature on Canadian Poetry. Reaching far beyond the exchange between French and English, this section presents a diverse group of authors and translators that reflects a multitude of cultural and historical intersections and conflicts. Now, Billey situates and introduces the poets and translators. Delve into the special feature here.

Global readers likely are aware of Canada’s official French/English bilingualism. What the literary world may not know about—and what Asymptote is delighted to spotlight in our Fall 2016 issue—is the range of Aboriginal and First Nations voices that are fundamental to Canada’s evolving identity. The Special Feature on Canadian Poetry introduces readers to three of the approximately sixty distinct Indigenous languages spoken in Canada.

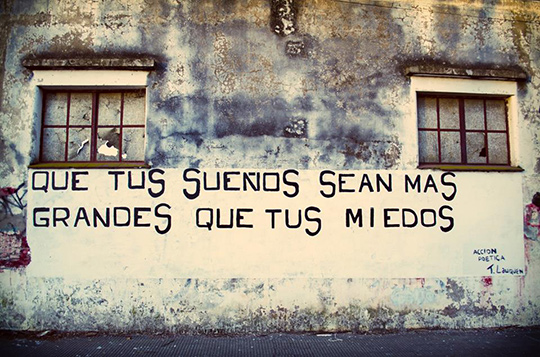

Multilingual poems by acclaimed poet Duncan Mercredi are a crystalline example of the verisimilarity that unites the Fall issue. Duncan’s brother Joe translated the English portions of Duncan’s poems into their native Cree, a language whose dialects nearly span the entire North American continent. Joe’s line-by-line translations became, and are recognized as, part of the poems rather than separate works. The poems are unified though their dual-linguistic nature, exacerbating and expressing the ambivalence of a First Nations poet writing in English.