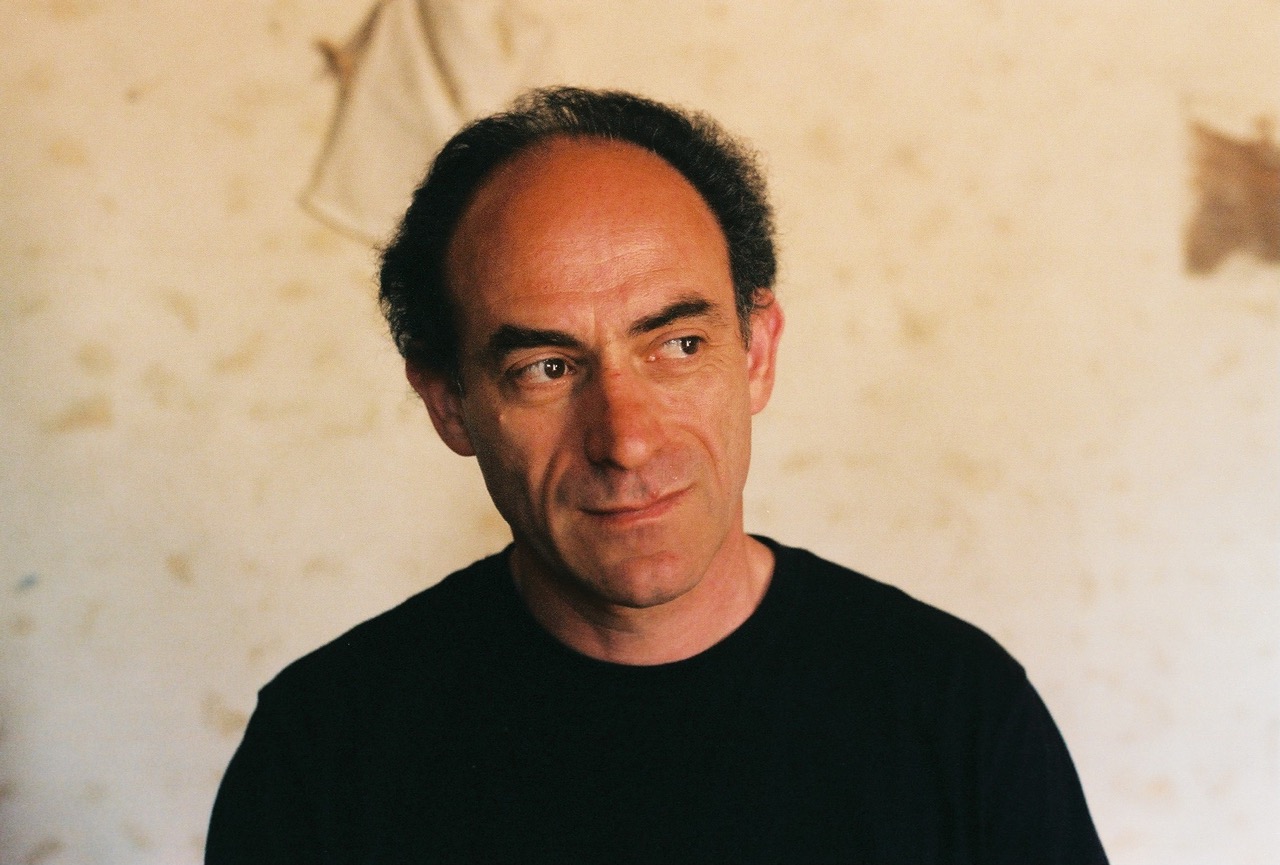

Denis Hirson is a South African poet living in Paris. He is the author of six books, exploring the memory of South Africa under Apartheid. Hirson is a translator of Breyten Breytenbach and the editor of two anthologies of South African poetry: The Lava of This Land: South African Poetry 1960-1996, (Northwestern Press, US; Actes sud, France, 1997), and its recently published companion, In the Heat of Shadows: South African Poetry 1996-2013 (Deep South, 2014). Hannah LeClair’s conversation with Denis begins with a discussion of his role as the editor of these anthologies, and delves into the many facets of his work, from his early translations of Breytenbach, to his readings and performances in concert with long-time collaborators Sonia Emanuel and saxophonist Steve Potts, to his own writing, which frequently crosses the border between poetry and prose.

Hannah LeClair: In the Heat of Shadows is a companion to The Lava of This Land, the first anthology of South African poetry you edited. And it first appeared in French, under the title Pas de blessure, pas d’histoire, in the wake of a festival organized by the Biennale international des poètes en Val de Marne in 2013. Can you talk about your work on this project? What was it like to bring together a multi-lingual collection of poets in this context?

Denis Hirson: It was in irresistible invitation. I was asked to help choose the poets who were going to come and participate in the Festival—I should add that this took place in the context of a larger event which the French term “une saison”— a season of cultural exchange with other countries— in this case, South Africa. The first part of the Saison took place in 2012, with South Africa hosting French cultural events, and the second part of the exchange took place in France, in 2013. Pas de blessure, pas d’histoire was an anthology produced as a result of the festival, and included the work of the fourteen South African poets initially invited to participate, along with fourteen others. It was strange to put together this anthology in French before bringing it out in English; I did that a year later, changing the content slightly. I should add that the publisher was Deep South in Grahamstown, South Africa – the press run by my friend Robert Berold, who was one of the poets invited to Paris at that time.

HL: You collaborated with a number of translators to bring together work originally written in Zulu, Xhosa, and other African languages, as well as Afrikaans. What was the process of translating all this material into French like?

DH: Well, most Afrikaans poems went directly from Afrikaans into French. During this process, I worked with two excellent translators—Georges Lory and Pierre-Marie Finkelstein. For the other languages, the poetry first went through translation into English. This involved too much filtering, in my opinion. But I did the best I could—I can understand Afrikaans, but no other language specific to South Africa—and referred back as far as I could to whatever touchstone I had available to me, making sure that the translations stood up poetically. The majority of translations into French were the result of collaboration between myself and Katia Wallisky, whom I have worked with for thirty years now. We have found a way of entering the French language together, in a way that is particularly appropriate for South African poetry. In general, French tends to be more conceptual, less concrete and cinematographic than English; it has an airy, fluid feel to it, while the music of South African poetry is often sparse, raw, and spiked with social difficulty. As a result, translating this poetry has sometimes been tough, but the result has been extremely rewarding. I think I can say that all the poems in Pas de blessure, pas d’histoire would easily stand up to the acid test of a public reading. Many have already done so.

HL: Could you talk a bit about the anthology’s titles, the French and the English?

DH: I should just slip in that the title of the earlier anthology, The Lava of This Land, is a quote from a poem by Tatamkhulu Afrika. That title reflected what I saw as the malleable, flowing, politically hot and poetically innovative South African territory of the post-1990 years, following Mandela’s liberation. So that was the title of the first anthology. The title of the second anthology, in French, is Pas de blessure, Pas d’histoire—

HL: And that comes from one of your own poems, doesn’t it?

DH: Yes—“No wounds, no history.” I put down a number of quotes from the anthology, and got people to vote for them. I think it’s a very good title, because of the way it encapsulates the idea that history, both intimate and social, can be generated by the wounds we endure, but it just doesn’t work in English. I generally like finding titles, but this title did not come easily. It was ultimately triggered by a poem in the anthology by Karen Press, “Praise Poem: I saw you coming towards me.” There’s this line: “Our clothes shine in your hot shadow.” I think what happened is that phrase hit another phrase in my mind, which was “In the heat of the night.”

HL: Like the Sidney Poitier movie?

DH: Yes. It’s an unspeakably powerful film, in which the strength of the central black character is only underlined by the blunt racial prejudice of his white counterpart. So, there’s the heat of the night—the idea of hot shadows, of the emergence of new power in South Africa, and also the emergence of what has been unseen—the forces at work outside of the light, mysteries that the intelligence cannot grasp, and that poetry reaches for. Shadows are what one is very conscious of in the heat of South Africa. And they have to do with the shades—ancestors, in the South African context. Vonani Bila begins his beautiful long poem, “Ancestral wealth,” with the words, “Under these tall thorn umbrella trees/ My ancestors dwell.” And in one of his poems, the Xhosa praise-singer Bulelani Zantsi announces, “When I present myself to you I first build a highway with the ancestors.” All this is to say that the past lies deep in the shadows of today’s South Africa. As for “the heat of shadows,” for me this phrase works at many levels. I think not only of the heat of the day—or the night—but also the heat of creation, the heat of what happens when people are not happy, the heat of working with the complex, contradictory energies of the country that surface in today’s poetry; the heat of despair, and sharp awareness, and intimacy— all of which appear in poems included in the anthology.

HL: How do all those images speak to your impression of what’s happening to poetry in South Africa today? What has changed since 1997, when The Lava of This Land was published?

DH: Well, let me start by saying this: It was much easier to do The Lava of This Land than to do In the Heat of Shadows. An anthology of that sort hadn’t been done before, so I felt I was, in many ways, really participating in something new. I started becoming interested in putting anthologies together in the wake of the changes that took place in South Africa in the 1990s; the work was, among other things, a way of reasserting my connection with the country after fifteen years of living in France. The idea of putting poets working in different languages side by side was relatively new, as was the mix of styles and voices working at very different registers. I was very excited by the work that had recently been published in South Africa, particularly in the magazine New Coin under the editorship of Robert Berold; but I also had the advantage of living in France, so that I was not subject to the views of any one school of poetic thinking inside the country. The political and social context in which I was working at the time gave a sense of coherence to The Lava of This Land. The most recent work in that anthology was written at a time when poets were experiencing a deep shift in ground, and wondering what kind of land they were writing out of. This in turn allowed me to look back as far as 1960, the year of the Sharpeville massacre, which created a political earthquake in South Africa. I am not a determinist, but I thought it interesting to think that round about 1960, when “the winds of change” (as British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan put it) were crossing Africa, poets in South Africa, particularly white ones and even more particularly some white English-speaking ones, were beginning to break away from a more European voice to find one more appropriate for the place where they were living. This in turn allowed for more meeting points between these poets and the black and Afrikaans poets whose work I saw as having been closer to the human and physical landscape even prior to the 1960s. In thinking about all this, I was influenced by JM Coetzee’s book White Writing, in particular his essay on the work of the South African poet Sydney Clouts. I saw something of the order of a very loosely shared – even if hybrid—South African tradition of poetry, emerging in the 1960s and coming to fruit in the 1990s.

On the other hand, putting together In the Heat of Shadows became a way of taking the temperature of poetry in South Africa, between the time of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1996-98, which was also when the previous anthology ended) and 2013, which happened to be the year of the Biennale festival. I found that many poets were still concerned with the memory of apartheid, but were no longer entirely leashed to it; poets are freer now, though they are also increasingly disillusioned with the new regime. At the same time I found that, the imagination of some poets had considerably stretched out in terms of time and space. Ancestral memory, always present in traditional praise poetry, was now more integrated into contemporary work; there was also now reference to different historical periods, Stalin’s Russia, Rimbaud’s Abyssinia. You could see that poets were travelling more, that they were more ready for laughter and—perhaps most importantly—for fresh formal experiments: I am thinking particularly of the long poems by Joan Metelerkamp and Katharine Kilalea.

HL: Why have you turned to the anthology as a format or a form?

DH: Recently, I was reading a book of poems by Yehuda Amichai translated by Ted Hughes, who says, Amichai’s work “sounds more and more like the undersong of a people.” And this phrase hit me between the eyes. I think that, ultimately, putting together these anthologies is an attempt to capture something of the undersong of a people. It’s certainly impossible for me to write anything vaguely resembling the undersong of a people. It is possible to grasp—to collect together, to play with, to weave together—a series of works in an anthology, which might together compose something on the order of the undersong of a people. In fact, given the way in which South Africa has been so deeply divided for so many centuries, an anthology is a perfect way of transcending frontiers, because you put, side by side, poems by these different people writing in different languages, and out of different traditions: in South Africa, there are the various traditions of English and Afrikaans-speaking poets, there is traditional black praise-poetry, protest poetry which also has roots going back more than a century, township poetry which brings many languages into a single poem, and so on.

HL: And the process of choosing pieces to put in an anthology—

DH:—is, in one way, a form of collaboration with particular writers, particular poems. It’s a sharing that happens at the frontier—at the boundary of their poems. It takes a lot of time. It involves trying to find a connection with these poems, though they may be far from one’s own preoccupations; and finding connections between poems by different poets, though they may be far from each other. It’s a process of creating resonance within the covers of a single book, while at the same time trying to grasp the full range of work available—which, for me, meant collaborating with a number of people, and particularly South African poets themselves. In the end, this work feels like the act of writing itself—an intellectual and physical experience, an act of total involvement. It also means trying to hear many kinds of music, not at all an easy process for someone like me, who was brought up in the monolingual confines of predominantly English-speaking Johannesburg.

HL: How have you taught yourself—or attuned yourself—to this music?

DH: I think of one moment in particular—one of those moments when you realize, while it’s happening, that it’s happening in a way that’s fundamental to you. I was in South Africa, at a poetry reading in Grahamstown in the early 1990s. Wally Mongane Serote was reading there. I had first read his work twenty years earlier, I also knew him personally. But at that moment, listening to him during the reading, I realized that I was hearing his poetry as if for the first time, and the words were going right inside me. I also realized to what extent I had resisted those words previously. What was it I was resisting? Whether this was a white South African resisting Black words, or whether there was just something in his music that I couldn’t get into before, or whether the form of his writing on the page didn’t fit into the neat little squares that one wants to put words into when one’s writing a sonnet, or for whatever reason… I heard his music then. It came flooding into me, and I realized how much I hadn’t been hearing beforehand.

HL: You edited The Heinemann Book of South African Stories with Martin Trump, and The Lava of this Land: South African Poetry 1960-1994, before working on In the Heat of Shadows.

DH: Firstly, in my case I think this question of anthologies all begins with the notion of collecting. As a child in South Africa, I was a collector; my room was a museum. And my favorite collection, at least for a certain period of time, was beetles. I wasn’t very scientific about it, but I was interested in them aesthetically, and I’m sure if I dug deeper, there would be some interesting symbolism involved: beetles hide in all kinds of places, under rocks, in dung, in flowers, and then fly off into the air; they are earth creatures and air creatures. By the time I got interested in poetry—I was still a collector, and in fact I co-edited an anthology of student poetry in Johannesburg. Secondly, even though I had read some South African writing while still living in the country, my interest deepened once I came to Paris, in 1975.

HL: What changed for you in Paris?

DH: In Paris I started working in the theatre, speaking French, doing what people need to do to camouflage themselves in a new environment. I didn’t really choose France for its culture—after being in London, I chose it as the closest available place of pure disorientation. I see this, in retrospect: that learning a foreign language is one of the deepest forms of disorientation one can possibly undergo. As far as the world of South African literature goes, there were two important moments for me in Paris. The first happened when I was working as a parking attendant at the theatre complex of the Cartoucherie de Vincennes. I told somebody to get his car off the grass, and instead of taking me seriously, he laughed at my accent and asked me where I was from. And when he found out I was from South Africa, he invited me to read some poetry at a public event—some of it by Breyten Breytenbach, in Afrikaans. In order to fully understand what I was going to read, I went to Georges Lory, a Frenchman who was translating Breytenbach into French at the time. And I learned how to read Breytenbach’s poetry through the French, because my Afrikaans just wasn’t good enough. Breytenbach had received a prize while in prison, the “Prix des sept,” which awarded him publication by seven different publishers in seven different languages. Georges Lory was doing the French, and—thanks to a lot of hard work—I ended up doing the English: In Africa Even the Flies are Happy: Selected Poems, 1964-1977 (John Calder, 1978). The second important moment was Mandela’s release from prison, in 1990. I wasn’t even going to watch Mandela come out of jail, but some South African friends invited me to come over and watch the event with them, on television. It filled me with overpowering emotion, which was completely unexpected. When I got home, I just switched on television and I didn’t budge: I just waited for Mandela’s image to come back on the screen over and over again. That’s all I wanted to see. My emotion had partly to do with the political symbolism of this man, who represented so much, emerging from the deep freeze of history. Another dimension was personal. When my own father came out of jail in 1973, after nine years as a political prisoner, it had been a very private and a very wrought event. When Mandela came out of jail, I felt able to express emotion openly in a way that I hadn’t been able to when my father was released. I was suddenly pulled back into the South Africa I’d left behind. My response was, firstly, to write about this and, secondly, to seriously read South African writing, familiarizing myself with it in the same obsessive way I function on all sorts of levels. It got into my teaching, my travels; books piled up at my bedside, everywhere, like sea-sand in your shoes. I needed anthologies for my teaching and I was dissatisfied with what was available, so I decided to put them together myself, starting in 1994 with The Heinemann Book of South African Short Stories, in collaboration with Martin Trump.

HL: Tell me a little more about your experience with translating Breytenbach. What was it like to begin gaining access to this text through French, a language that you were still familiarizing yourself with at the time? How did that experience impact your practice of translation?

DH: If I’d had known the least bit about what I was doing, I just wouldn’t have dared – I was so naive. As you have pointed out, I was just discovering French, and here was this other language, Afrikaans, arriving on my doorstep. I had learnt a few rudiments at school, earning the absolutely lowest pass mark in my final exams—we all had to learn Afrikaans, South Africa was a country with two official languages at the time. I did need to obey Afrikaans in the army, but that wasn’t very difficult, because everyone was doing the same thing anyway. And apart from that, as I said in our previous interview, I grew up in an English-speaking stronghold where we didn’t even need to understand the mother-tongue of our servants, although I did study Zulu for a year at university. English was the language of power, and anybody who spoke Afrikaans or an African language was simply obliged to speak it in order to survive there. South Africa was geo-politically separated from the continent, and English-speakers were separated from anything other than their second-class colonial lives. And besides, Afrikaans was the language of oppression, the tongue of those who had locked my father up. But in France, in 1976, with just a bit of French in my pocket, I found not only the time and energy, but more especially the desire to go backwards, as it were, into the virtual ignorance of another South African language, which I had never wanted to confront when I had lived there. It was like undoing a knot that had been tied; going back in time to undo a knot of incomprehension. So, between Georges Lory’s French translations, and my English-Afrikaans dictionary, there I was, hobbling along from one metaphor to the next, trying to work out what Breytenbach was saying.

HL: So—you began by playing it by ear? What did you learn? Did you come up with set of practices, a method?

DH: I’ve always thought of myself as a writer rather than a translator, and I’ve always thought of translation as another kind of writing. But from 1975 when I arrived in France until about 1983, when I started working on The House Next Door to Africa, my first book, none of my writing survived. I went to poetry readings, I spoke to writers, and so on, but nothing that I did for myself at that time lasted. On the other hand, I immersed myself in Breytenbach’s work— his music, his imagery, his world— and shifted my perspective from the somewhat troubled reality of trying to make a space for myself here in Paris. I also had the attractive prize of publication, which was a chance to make space for myself as a writer in the world. I suppose I was also working with the buried knowledge that someday my own writing would also be at stake.

HL: Can you describe the space you found for yourself, as a writer? How do you enter into that space?

DH: Well, it’s a space of concentration, a space where the next word or the next silence is what’s at the heart of that time, where you’re not going to answer the next email or phone call—where you are in a state of extreme listening. I found myself in a strange space in Paris: French language, French culture—it was all strange to me. In a way, Breytenbach’s language, his words, were relatively more familiar to me than what I was actually living through on a daily basis, in spite of the strangeness of Afrikaans. I didn’t have any real theory of translation, but I do remember that when I had an intense discussion with Georges Lory, who was translating Breytenbach into French, and Adriaan van Dis, a Dutch writer who was translating Breytenbach into Dutch. Adriaan van Dis was saying that you had to give yourself over completely to the other—to the original writer—and I was saying, No, you had to make a poem that was going to be accessible to the reader in the language that you were translating into. This is the whole issue present in the proximity of the two Italian words traduttore and traditore, translator and traitor: to what extent, if at all, does one need to betray the original in order to produce a poem that’s going to be readable in your own language? To what extent does the basic architecture of one’s own language shift to accommodate the needs of the original poem? It is certainly highly satisfying to read a translation which works as such but where one can also feel the passage of the original language.

HL: All these different approaches, it seems to me, really are questions about energy—how you are approaching the energy of the original text and how you see it entering you; whether you see yourself as a conduit or someone who’s building a bridge.

DH: Well, both of those, I would say. Can you not be the receptive hollow of the conduit that also fills out into the curve of the bridge?

HL: There’s a way in which, either very humbly or very hubristically, you could see yourself as merely a mouthpiece, or a special, prophetic mouthpiece for someone else’s work. What you said about being in a state of “extreme listening” really resonates with what you said in our previous conversation, about hearing the music of Wally Serote’s poetry for the first time.

DH: It’s interesting that you should put that together. For me, music, listening, writing and public reading all come together.

HL: Performance has always been important to you, hasn’t it?

DH: In 2000, when I was doing a radio program with France Culture, I heard Sonia Emanuel reading some Haitian poetry, and thought to myself, If I ever do a reading, that’s who I want to do it with. We began working together in 2001, doing readings in schools and libraries, bookshops and cultural centers, in a prison, during festivals. I love collaborating with her. We did a performance which involved both French and English. I read in Afrikaans as well. We had a sort of repertoire. I played a few musical instruments, and I did a little bit of speaking about South African history. Later, we also began working with the saxophonist Steve Potts, and still do. Up until very recently, South Africa has been a very positive reference point in France. During the time of apartheid, there were a lot of protests—and French people very easily associate culture with protest.

HL: Has your role—the role of your performances—shifted over time?

DH: Well, it has become less pedagogical, and the performance itself has become denser, perhaps more intense. But we haven’t had a call for one in the last few months. Until recently, we were doing about ten of them every year, all over the country. I have always been interested in poetry that moves from the intimate to the social, that is an act of witnessing but also speaks of the self—the kind of poetry written by Szymborska or Prévert, Amichai or Milosz. I’m interested in poetry that is accessible enough, clear and deep enough to communicate all kinds of things. Here in France someone like Prévert has almost no successors apart from a singer like Allain Leprest, who died recently. Many people who read novels can’t name a single poet who lives and works here and is less than eighty years old. Our performances have become less about South Africa, and more a way of saying, Look: Here is direct, accessible poetry for you, which happens to come from South Africa.

HL: Would you talk briefly about your own writing? How has experience of moving between languages and cultures made its way into your own projects?

DH: My own work began to be translated into French in the late ‘80s. At first, I didn’t want to have much to do with the translation. And I didn’t want to read my work in French, in public. It was a long time before I really felt that my work could engage with a French audience. But In 2006 I began working with Katia Wallisky on a collection of my poetry to be published in French. Katia gave me some initial drafts of translations, I looked at them and thought to myself, This is not how I want to see myself in French. That was a relatively new idea, to think, How do I want to be read in French? In one poem, about Cape Town in the 1960s, I talk about a squat “hopping with fleas”, and in the end this was what I focused on with Katia during a difficult discussion in which I convinced her that we should translate together, to try and shift the more conceptual possibilities of French to get down to the hopping of the fleas (which, in this particular case, turned out to be impossible). As soon as the French language fills up with physical detail, with the concrete verbs and objects of which so much of English writing is made up, it loses its own strength—which is far more atmospheric and removed. So, Katia and I struggled with those exemplary fleas, and then in the end decided that we were going to translate together. The book ended up being called Jardinier dans le noir (Le temps qu’il fait, 2007), which soon afterwards became Gardening in the Dark, in English (Jacana, 2007). And through that work, I started involving myself in the French language in a very different way.

HL: So, that comes directly out of your other experiences with translation—now you were able to turn the process on yourself. Are French and English mixed together, in your mind?

DH: Not exactly mixed now, but both strongly present. There have been all kinds all kinds of steps over the past 40 years. I think the first stage is disorientation. You get a sore mouth because you don’t know how to say “tu,” and you say, “too.” And then you eventually land up, after a certain number of months, being able to produce something like a rudimentary conversation. And then this other language starts entering your life, and displacing the English, and you realize that you’re going through some kind of transformation in which you’re making space for this new creature in your head. Then, of course, your children speak to you in French—and they correct you in French! It’s only much later that you get to correct them, which is sweet revenge. In my case, most of this evolution was in spoken rather than written French. Remember that I didn’t fall in love with the French language—I just happened to be here in Paris. Only later did I realize how useful it is to me, psychically, to be speaking a second language. But I did take it on, and I stayed on. Translating my work in to French was the crystallization of a process that had already been in movement for many years. Then, in 2012 something happened to me – this could be the subject of another interview – which led me to start writing directly in French. Next year, I will publish my first untranslated book here; it has just been accepted by Le Seuil. And it is about the many-splendored strangeness of speaking French.

Hannah LeClair is a writer and recent transplant from New York City to Vermont. She reads fiction for The Mud Season Review.

*****

Read More Interviews: