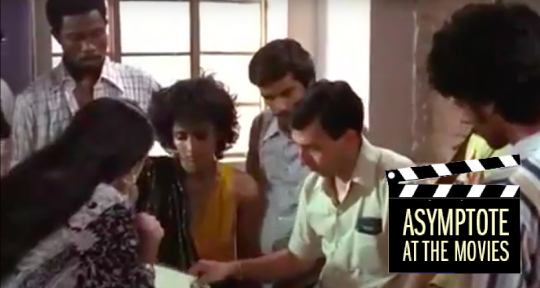

Of her 1989 film, In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, Arundhati Roy writes: “I loved the quirky, spontaneous performances. I loved the fact that there were no ‘beautiful’ people in it. I loved the egalitarian friendships between the boys and girls. I loved the corny clothes, the absurd glasses, the ridiculous hairdos, the uncertainty, the joy and the sadness of it . . . It was from another time . . . I ache for the innocence of it.” Indeed, the film is potent with the tender touches of youthful idealism, fearlessly authentic to its characterisations of young architecture students in 1970s India, and an early emblem of Roy’s intrepid criticisms against the evils of her time. In this edition of Asymptote at the Movies, Editor-at-Large for India Suhasini Patni speaks with Blog Editors Allison Braden and Xiao Yue Shan about the complex role Hinglish plays in the film, the depictions of class and social mobility, and how art can arise from the myriad places in which various languages meet.

Suhasini Patni (SP): Before Arundhati Roy became famous for her Booker Prize-winning novel and Pradip Krishen became an important environmentalist, they worked on the film In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, which was screened late at night on Doordarshan in 1989, then largely forgotten by the Indian audience. However, it later went on to win two National Awards (both of which were returned to protest the government’s growing intolerance) and became a cult classic.

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first Hinglish film ever made in India. Critics found it difficult to categorize the language of the film; some called it an English language film—which does disservice to the mouthfuls of Hindi and Punjabi that form an integral part of the dialogue—and some called it a trilingual film, which doesn’t showcase the Indianness of the English spoken. English that is remolded to include mispronunciations and Hindi slang (“Kya maal hai. Hello sweetheart lovely,” says a catcaller to Radha).

Discerning commentators found it difficult to admit an entire film existed in this “nonsense” language. Even the title itself is gibberish: In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones. The students in the film let us know what “those ones” are, but at the time of its release, the title was allegedly seen as inaccessible and alienating, and Roy was asked not to use it. But it’s exactly this mismatched, nonsensical language which makes for an endearing experience—a film ahead of its time, as people say.

The dialogue captures the porousness between Hindi and English. Code-switching in bilingualism is not new, but Hinglish, as Roy has written it, really grasps the way social mobility operates in a cosmopolitan city like Delhi. For the upwardly mobile, Hinglish is a language of survival. For those who cannot speak the hegemonic, pure, Sanskrit-ised Hindi, Hinglish helps to adapt to life in the capital. And in any case, North Indians have always spoken Hindustani, a Hindi that generously accommodates Urdu and other languages and dialects. Hinglish is arguably a “modern” version of Hindustani.

I’m interested in knowing what you think about the film, especially considering you’re not native Hindi speakers.

Allison Braden (AB): What a charming film! I agree that the movie’s collegial atmosphere and the students’ easy rapport depends largely on the code-switching; omitting the Hindi and Punjabi in favor of English only would have done away with one of the story’s most authentic elements. For viewers who don’t speak Hindi, some of the linguistic diversity naturally gets lost behind the subtitles, which appeared for the English, Hindi, and Punjabi dialogue in the version I watched, but the languages’ relationship to class remains evident. Arundhati Roy’s character, Radha, clearly struggles with the social mobility issue you bring up, which she articulates toward the end of the movie. She specifically mentions how her position as a student at the National School of Architecture requires her to speak a language that ninety percent of the country can’t understand. Social mobility is also explicitly referred to in the eponymous Annie’s initial thesis project—a plan to line India’s extensive train tracks with fruit trees and encourage the country’s flood of rural to urban migration to reverse course. Despite his enthusiasm for the idea—he even writes to the prime minister about it—his classmates respond dismissively. I was struck by the moment when his partner rebukes him after interpreting the plan as a suggestion that she return to her village. He explains that he’s speaking about a general issue, not her individual situation, but the exchange was such an effective illustration of how those larger issues affect so many individual lives.

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): Far from being objectionable, for those of us who find language to be an object of fascination, the varying, generous, and emancipated dialogue of the film is one of its overarching attractions—endearing, as you say, Suhasini. Though, of course, I can imagine how difficult the melange may have been to navigate sans subtitles. READ MORE…

What’s New in Translation: August 2021

New work this month from Lebanon and India!

The speed by which text travels is both a great fortune and a conundrum of our present days. As information and knowledge are transmitted in unthinkable immediacy, our capacity for receiving and comprehending worldly events is continuously challenged and reconstituted. It is, then, a great privilege to be able to sit down with a book that coherently and absorbingly sorts through the things that have happened. This month, we bring you two works that deal with the events of history with both clarity and intimacy. One a compelling, diaristic account of the devastating Beirut explosion of last year, and one a sensitive, sensual novel that delves into a woman’s life as she carries the trauma of Indian Partition. Read on to find out more.

Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse by Charif Majdalani, translated from French by Ruth Diver, Other Press, 2021

Review by Alex Tan, Assistant Editor

There’s a peculiar whiplash that comes from seeing the words “social distancing” in a newly published book, even if—as in the case of Charif Majdalani’s Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse—the reader is primed from the outset to anticipate an account of the pandemic’s devastations. For anyone to claim the discernment of hindsight feels all too premature—wrong, even, when there isn’t yet an aftermath to speak from.

But Majdalani’s testimony of disintegration, a compelling mélange of memoir and historical reckoning in Ruth Diver’s clear-eyed English translation, contains no such pretension. In the collective memory of 2020 as experienced by those in Beirut, Lebanon, the COVID-19 pandemic serves merely as stage lighting. It casts its eerie glow on the far deeper fractures within a country riven by “untrammelled liberalism” and “the endemic corruption of the ruling classes.”

Majdalani is great at conjuring an atmosphere of unease, the sense that something is about to give. And something, indeed, does; on August 4, 2020, a massive explosion of ammonium nitrate at the Port of Beirut shattered the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. A whole city collapsed, Majdalani repeatedly emphasises, in all of five seconds.

That cataclysmic event structures the diary’s chronology. Regardless of how much one knows of Lebanon’s troubled past, the succession of dates gathers an ominous velocity, hurtling toward its doomed end. Yet the text’s desultory form, delivering in poignant fragments day by elastic day, hour by ordinary hour, preserves an essential uncertainty—perhaps even a hope that the future might yet be otherwise.

Like the diary-writer, we intimate that the centre cannot hold, but cannot pinpoint exactly where or how. It is customary, in Lebanon, for things to be falling apart. Majdalani directs paranoia at opaque machinations first designated as mechanisms of “chance,” and later diagnosed as the “excessive factionalism” of a “caste of oligarchs in power.” Elsewhere, he christens them “warlords.” The two are practically synonymous in the book’s moral universe. Indeed, Beirut 2020’s lexicon frequently relies, for figures of powerlessness and governmental conspiracy, on a pantheon of supernatural beings. Soothsayers, Homeric gods, djinn, and ghosts make cameos in its metaphorical phantasmagoria. In the face of the indifferent quasi-divine, Lebanon’s lesser inhabitants can only speculate endlessly about the “shameless lies and pantomimes” produced with impunity. READ MORE…

Contributors:- Alex Tan

, - Fairuza Hanun

; Languages: - French

, - Hindi

; Places: - India

, - Lebanon

; Writers: - Charif Majdalani

, - Geetanjali Shree

; Tags: - Beirut 2020 explosion

, - diary

, - disaster

, - Indian Partition

, - motherhood

, - recovery

, - social commentary

, - trauma

, - womanhood