Amidst the uncertainty of what the new year will bring, one surety is that wonderful literature remains to be discovered. In our first selections of new translations for 2021, there is a masterclass in historical fiction about a chess champion whose awe-inspiring trajectory was regrettably tainted with prevailing prejudice; a Dutch memoir that reconciles public and private definitions of sexuality, personhood, and recognition; and a Korean novel that beautifully illustrates that median pain between a love of life and an acknowledgement of its ephemerality. Read on to uncover their discrete and distinct gifts!

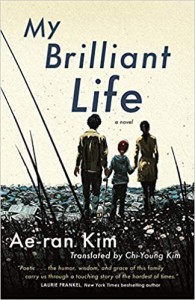

My Brilliant Life by Ae-ran Kim, translated from the Korean by Chi-young Kim, Forge Books, 2021

Review by Ah-reum Han, WoW Editor

Meet Areum Han, the sixteen-year-old boy with a rapid-aging genetic disorder that is at the palpitating heart of Kim Ae-ran’s bestselling novel, My Brilliant Life, translated by Chi-young Kim. “This is the story of the youngest parents with the oldest child,” writes young Areum, in the prologue to his own story. Readers learn some simple truths about Areum from the get-go: he has an uncanny way with words, he loves his parents deeply, and he doesn’t have much time left. But don’t be fooled; this story is not about the sick, nor is it about overcoming suffering. This quirky, bighearted book crackles with life on every page.

My Brilliant Life is a bildungsroman in fast-forward. We enter Areum’s life on the cusp of his final act—and, incidentally, at the age that his own young parents had him. What ensues is a tale that is tender and funny, startling and sad. He writes about his condition:

People say it’s a miracle that I’ve lived this long. I think so, too; not very many people in my situation have lived past their sixteenth birthdays. But I believe that the larger miracle exists in the ordinary, in the living of an ordinary life and dying at an ordinary age. To me the miracles are my parents, my aunts and uncles, our next-door neighbors, the middle of summer and the middle of winter. I’m no miracle.

We become familiar with this enviable “ordinary” through Areum’s watchful eyes, meeting his father, Daesu, who is equal parts foolhardy and brash but with a boyish charm, and Mira, his proud, sharp-tongued, and fiercely protective mother. We see how they each grieve privately and publicly; how they fight, curse, and joke; how they keep secrets to be kind. We watch their simple moments of ordinary miracles: eating shaved ice together, or laying on the living room floor with face masks on.

With Areum’s growing medical expenses, Daesu and Mira struggle to make ends meet, and reluctantly agree to let Areum go on a television show. Through this national exposure, Areum has new encounters with the ordinary. For one, he meets Seoha, a seeming kindred spirit and young girl who reaches out to him after seeing him on the show. Their email exchanges soon bloom into something more—the thrill of first love, tempered with the gravity of impending loss. As Areum’s circumstances quickly unravel, we ache for him to be a teenager with teenage-sized problems. We wish him the mistakes and failures, the freedom to pout and sulk.

In all this, Daesu and Mira do what they can to give Areum a normal life, and Areum knows it. This stereo vision—Areum’s awareness of his parents’ struggles and their lives both before and beyond his own—shows us how Daesu and Mira were also unceremoniously thrust into adulthood. My Brilliant Life is a coming of age tale, not just for Areum, but also for his parents, whose stories bookend his. This is a story that is very aware of its own symmetry: the two unlikely seventeen-year-olds who became parents; their child destined never to outlive them; and the stirrings of a newborn as their first slips away. The story folds into neat patterns that amplify life’s indifferent poetry. READ MORE…