1

thousands of thousands of kilometers away, from other breaks

the yellow mountains of Li Po and stone forests of Siberia were born.

then the water appeared,

burrowing, like roots, into the fractures.

the fog, in river valleys, suspends autumns and the reply of

church bells.

it knocks persistently at the doors to homes,

and under its influence, the yew-men descend to the banks of the river

to erect Jacob’s ladders upon which they’ll grow their grapevines.

if the afternoon’s flower falls open,

the men’s daughters will enter the river. they’ll play dead along the banks,

they’ll count the stones in the retention walls mentally until they lose track; they’ll laugh like wild.

look at how the moon shines at their feet,

tinging the burgundy of Mencía wine

as they grow

Enumerate things, one by one until all her fingers are hidden)

baptismal water and friends, the river carries away the reflections of an entire

Roman legion

devoted to the trepanning of a mountain. the river carries away the ends of cigarettes smoked

by my grandfather,

devoted to the trepanning of a mountain. It was years before I noticed

the parallel:

my father’s father built tunnels

all while he was having another child.

it wasn’t April,

breeding lilacs out of the dead land.

the same way we divert the river bed

to search for gold in its original depths,

we divert the fingers that discover a wound

to bandage it. and

we lull like this, and that

we lull like this,

and that.

Triptych

oil on canvas, my grandmother reproduces a scene from Millet

her right hand oscillates three times over,

sowing salt crystals in the face of the oncoming storm,

as if the sea’s currency were enough to save us. the girls

watch them dissolve upon contact with the cement patio,

and they’re jewels for a fraction of a second, something to point at

as they disappear.

the rain keeps the psalms from sticking to the little girls

and the hand that had been a pendulum returns to its hip; like a marigold, it knows

how to withdraw.

when you plant a bonsai, you do so away from the center to make

space for the divine.

much like her, casting out evil

from an apex.

oil on wood, my father says

that recruitment is an art

he keeps many things to himself: the hour in which the snow turns blue atop

Swiss mountains, his daughter’s first tooth, the shattering of his sternum

he keeps silent. I would never plant a bonsai.

he knows how to withdraw the shadow

from the bodies

of birds.

acrylic on paper, his daughter repeats

similia similiabus curantur as she traverses the patio. when

she was born, they tied stag beetle horns around her wrist.

a hundred kilometers to the west, the fishermen gather up

starfish to fertilize the soil. she doesn’t know this.

brazen,

she plants herself in the center and gazes upwards to capture the gleam of an erstwhile

Milky Way.

wing chun: on love as a martial art

they too grow quickly, like the weeds on a bird’s grave

let’s talk about that,

about what we allow ourselves the luxury of not literally understanding.

if light can propel a spaceship

do you still wonder who’s going to come out on top?

two friends talk over the table at a bar in the early morning.

one traces the outline of her eyelashes with the tip of her index finger, seems truly

affected

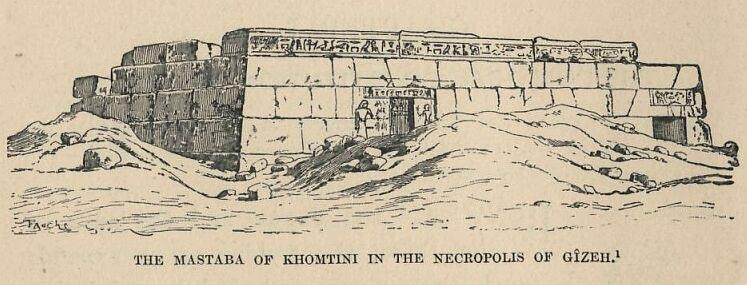

(her words form a mastaba in the other’s mind

a golden enclosure

—it makes sense that mastaba would come from the Arabic “talking place,” which also bears traces of the ancient Greek stibás, “bed of weeds”—

I gave him mare’s milk and healed his wounds with gentian violet powder,

thinks the one listening,

just the way it happens in Andean legends

as if a remedy’s effectiveness were measured by the shock it produces)

hidden in a forest while she meditates, Ng Mui observes

a battle between a snake and a crane. both facing center,

a splendor of orbits and slenderness, two verses

of unequal meter galloping out the mouth of their speaker.

Ng Mui watches and memorizes their movements,

their art.

there is no order that can function in the world

if we listen closely to her tale, the friend speaking maintains contact too.

she makes her opponent’s technique her own,

folds attack into defense,

aims not for vital points, but for those that will prevent movements

yet to come

behind the words, muscles

incandescence

wing chun, “eternal springtime chant”

the woman listening isn’t sure if her friend learned more from the crane or the snake.

the woman listening wonders which Egyptian amulet would suit the moment

(if Turkish ceramic fishes saved their wearer from drowning in 1335 B.C., what effect would that have here?)

the morning advances

in subcutaneous fashion, like venom secreted from a clamping of the jaws

a snake bite

matters little:

they linger, untouching, united in astonishment

like parallel fang marks in a victim’s flesh.