Incidental Interventions by Elena Ferrante, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein, Europa Editions, 2019

Early in her new collection, Incidental Inventions, Elena Ferrante describes her fascination with a portrait of a nun, displayed in the Pio Monte della Misericordia in Naples. Its artist is unknown, but Ferrante forms a relationship to the person behind the painting all the same, through the work itself. Although the life and experiences of the artist remain out of reach, Ferrante feels that she could give a name to the creator who is knowable through studying the work: a female name, Ferrante surmises, which would then be “the only true name used to identify her imaginative powers.”

As I began to reflect on this new collection of articles, I related to this desire to lend language to the snippets of truth that we grasp in life, and to search for meaning in others’ artistic expression. Back in 2018, reading Ferrante’s column for The Guardian as it was published week by week, I had formed an impression of these articles as a light yet thoughtful series of reflections on experiences from the ordinary to the dramatic. Reading about topics as diverse as feminism and the exclamation mark, I’d felt that I’d drifted along from colourful anecdotes in the author’s signature style, through to the often philosophical conclusions that felt natural, or even obvious, in light of the path I’d been encouraged to follow as a reader. In this process, I felt that I was getting to know the author, sharing in snapshots of her life, and feeling a sense of connection from the moments that felt relatable or right within my own world.

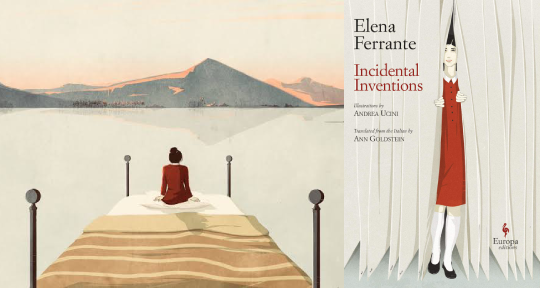

Maybe it was the cover illustration featuring someone peering through a curtain, maybe it was the changing political climate in which trust in written forms (and especially online forms) continues to dwindle, or maybe it was my own changing perspectives as a reader, but reading these articles again a year or so later, in their collected form, was an entirely different experience. This time, I was instead struck by Ferrante’s persistence in taking us behind the curtain, preventing us from blindly consuming anything she writes as pure truth, and reminding us that the columns we read on the Internet (however beautiful) are constructions of their authors. The authors, too, then, are constructions of their readers: recreated through the imperfections and interactions of our minds, our languages and our relationships with one another (real and imagined).

Approached by The Guardian to write weekly articles, Ferrante agreed on the condition that the editors would provide her with topics for each article. She describes this exchange in the introduction to the collection, reminding the reader these pieces are an interaction between the writer, the editor, and the world, rather than some self-contained truth transmitted directly from the writer’s mind. It is, as per the title, an incidental phenomenon. In one later article, Ferrante goes as far as to question whether reading more news articles can even help a person to understand the world at all. While her own articles are fully-fledged and articulate, the author refers to them as “seeds of novels,” and approached writing them “as an author of novels,” suggesting that, perhaps, certain ideas cannot fit within the fast-paced, carefully planned form of the newspaper piece.

Among these “seeds” are many thoughts about the relationship between writing and truth. One piece, conspicuously titled “The False and the True,” explores how even a deliberate experiment in the faithful representation of reality (in the form of transcribing a video interview with a friend), can present fundamental questions about truth. What we are left with when we try to record episodes of real life is an acute awareness that we can never fully tell the truth, though we might choose to tell a faithful story. This line between storytelling and lying plays out further in a story Ferrante tells about a childhood tendency to tell falsehoods in order to entertain friends: “I had the impression that they were truer than the truth,” she says. Still later in the book, she observes that families prefer to photograph only their children’s happy moments. She herself prefers to keep a photograph of her younger self that looks nothing like her own recollections of her adolescent appearance, but that reflects a version of herself that she would most like to believe existed. Perhaps this is the outlook of a self-aware fiction writer: the realisation that attempts to tell the truth always involve embellishments, inaccuracies, imperfections, or sometimes wild imaginings.

Outlining these tensions and limitations highlights an underlying frustration that is always present in my world, as a writer and editor: the inability to fully articulate my inner world through text. Ferrante contemplates this “artificial universe that is delineated by writing,” from questions of artistic expression to personal preferences regarding punctuation. And then she writes about her drive to represent the very things that we are most tempted to be silent about. These moments of silence-breaking, I thought while reading, are when it might be most relevant to take Ferrante’s advice: that a writer sometimes needs to break the rules of the language in order to bring themselves closer to the idea they are trying to express. Cultural silence on a topic could emerge from a social factor such as a taboo, or perhaps in some cases it could reflect a limitation of language, a struggle of representation in places where language might have evolved to gloss over something challenging or raw or abject. It’s a reminder that “reality can’t stay inside the elegant moulds of art; it always spills over, indecorously.” We cannot contain the world, in its multitudes and messiness, within the constraints of our text, even when we are claiming to write nonfiction.

To me, the author’s awareness of all these layers of linguistic limitations was clearest in a particular aspect of her style: the listing of multiple attributes, or multiple imageries, in order to reach out towards a more complex idea that could not be directly described through a single example, word, or concept. In these moments, the work seems to edge a little closer to poetry, asking the reader to pause at each comma and layer different ideas over one another, in the hope that some shared imagining might be reached at the end, in amongst the interactions and intersections of different words and images. For instance, in the article entitled “Fears,” the author builds a list of things she dreads, until I can picture all these terrors gathered, from “spiders, woodworms, mosquitoes, even flies” to the humans that brandish their “words of contempt, clubs, chains, weapons that slash or shoot, atomic bombs.” Holding this picture in my mind, reading towards the final sentence, it seemed so natural to conclude that “What perhaps should be feared most is the fury of frightened people,” like those who remained alive in the article’s introductory imagery, with their slingshots and knives and bombs. As a reader, I find myself drawn to such multiplicities, and the freedom to look for truth within their interactions and the gaps between: those incidental clashes of meaning that, for each reader, can be different, and therefore more powerful.

Reading Ferrante’s work in English introduces other multiplicities, too. There is, of course, the layer of translation. The reminder that we are reading a translation emerges most obviously in one passage in an article about friendship, when Ferrante tells her readers about the Italian word amicizia, and its close relationship to the Italian word for love, amare, a suggestion that would otherwise be lost on English-speaking readers. Although the language barrier might place some inevitable limits on how these texts reach English-speaking readers, Ferrante encourages gratitude for the meanings that we are able to convey through translators: “Translation is our salvation: it draws us out of the well in which, entirely by chance, we are born.” This thought served to remind me that, in fact, we are always viewing writing through many layers of interpretation, since we are all born in a particular well, equipped as it is with other writings, with other ideas, with other people. In reading translated work, then, we might get glimpses here and there of how our usual linguistic and cultural environment affects our understanding of life, friendship, and love.

Discussing the adaptations of her work into film and television, Ferrante again shares her views on the benefits of others’ interpretations, suggesting that, in the right hands, an adaptation can become more powerful than the original text. These interpretations are inevitably filtered through the biases of those doing the interpretation, however; Ferrante expresses a greater sense of ease in working with female directors, reminding us that the act of reading can never be separated from one’s context: culture, gender, class, and the many other factors that affect our realities. When we read a text, we are seeing ourselves reflected back. Although we might attempt to transcend these limitations—to understand the other—this might never be fully possible, and some others remain more within our reach due to their similarity with ourselves.

Reading these articles in their collected (and illustrated) form, I was particularly struck by these impacts of expectation and context when I reached an article about caring for plants. This new hardback collection introduces each article with a vivid illustration from Andrea Ulcini. Ulcini’s illustration for this article, called “Plants,” spoke to me of a peaceful interconnectedness: the roots of the tree had reached out to embrace their human carer, and this carer had in turn seemed to internalise these roots, reminding me of the natural cycles of life and death, and the ecosystems on which we depend. Yet, in the article that follows, Ferrante confides in her readers about a fear of being subsumed by plants, casting this apparently innocuous illustration in a new light. I revisited the illustration after reading the article, forced to reflect on the initial judgement that I made and readjust my understanding of what the artist might have wanted to say, and what the author likely intended. It was a moment in which the illusion of understanding the other had been shattered: I’d gone looking for the person behind the text and found myself gazing only at my own reflection. And yet, still, I felt the urge to keep going, to keep trying to understand, and to perhaps feel that sense of connection to the creator through the creation.

And, maybe, coming to see oneself clearly is a worthwhile pursuit in itself. Although truth might be an elusive thing in general, Ferrante stresses that, “it’s urgent that we learn to confront the truth of ourselves.” In a cultural moment when all things can feel all-or-nothing, it feels important to remember that we are all distanced by time, space, language, and the loneliness (and joy) of our individuality. When we read and write, we can give these experiences a name, and we can feel the truth of that name. This makes the collective experience of reading Ferrante’s articles a meaningful one, and an act of connection, even if we are all in fact thinking different thoughts in different languages about an author who is still, despite her fame, in many ways an unknown artist.

Illustration by Andrea Ulcini

Angela Glindemann is a queer writer living in Melbourne, Australia. She works in educational publishing and volunteers as a copy editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: