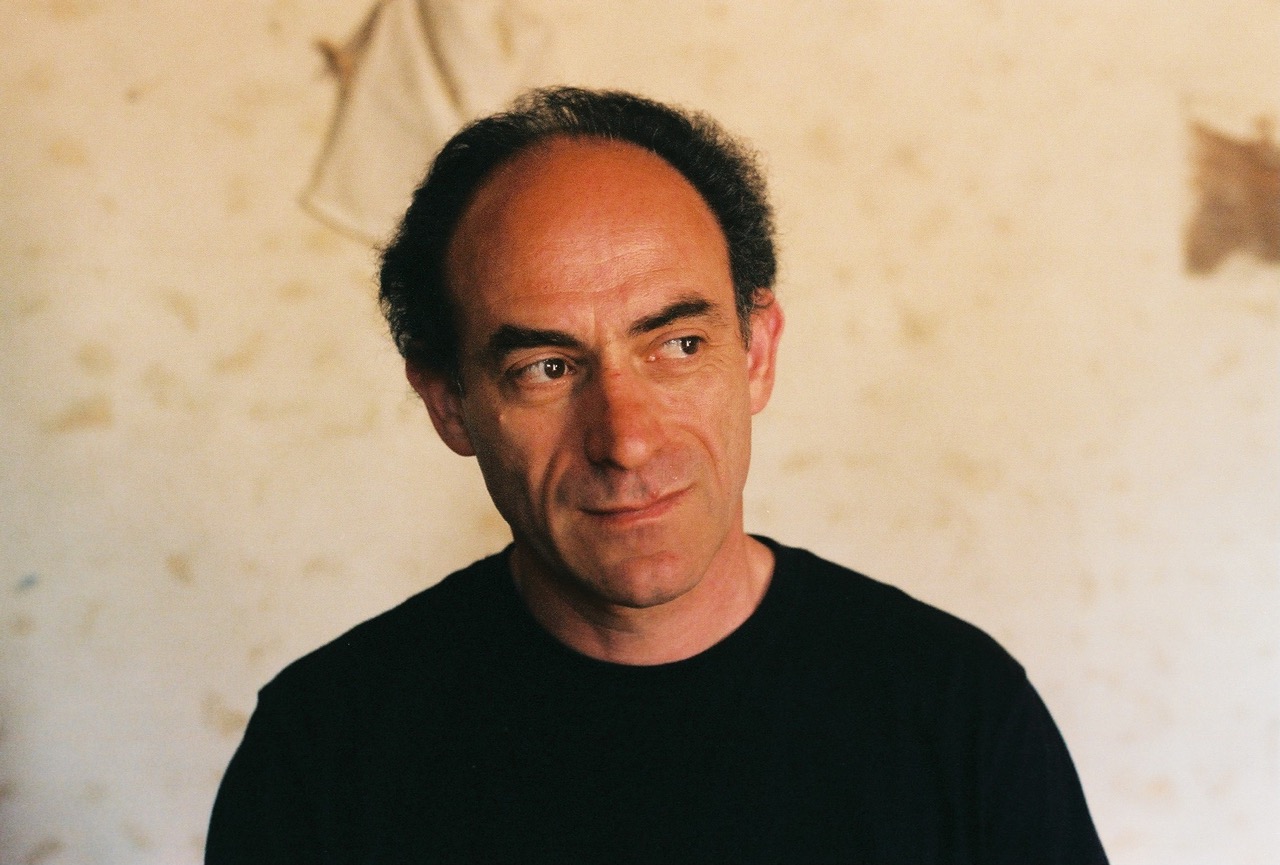

Gazmend Kapllani is an Albanian-born author, journalist, and scholar. He lived in Athens for over twenty years. He received his PhD in political science and history from Panteion University in Athens, with a dissertation on the image of Albanians in the Greek press and of Greeks in the Albanian press. In addition, he was a columnist for Greece’s leading daily newspapers. Kapllani has written his first three novels in Greek, which is not his native language. His work centers on themes of migration, borders, totalitarianism, and how Balkan history has shaped public and private narratives.

Kapllani’s first novel A Short Border Handbook (Livanis, 2006) has become a best-seller and has been translated into Danish, English, French, Polish and Italian. His second novel, My Name is Europe (Livanis, 2010), has been published into French. The Last Page (Livanis, 2012) his most recent novel, has been translated into French and was short-listed for The Cezam Prix Litteraire Inter CE 2016. Since 2012 he has been living in the US, where he was a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, Visiting Scholar at Brown University and Writer in Residence at Wellesley College. Kapllani currently lives in Boston and teaches Creative Writing and European History at Emerson College.

Gigi Papoulias has a chance to sit down and talk to Kapllani on his work, language, and borders.

Gigi Papoulias (GP): You seem to have a passion for languages. You are fluent in five languages. Were you born into a multilingual family?

Gazmend Kapllani (GK): Actually I was born in a shack. My father’s family was persecuted by the communist regime and was driven out of their house in the countryside and punished—sent to live in a shack on the outskirts of my hometown Lushnje. They were considered “enemies of the regime” because they were wealthy landowners. Stalin did the same with the so-called “kulaks” in the Soviet Union.

I grew up surrounded by a large group of monolingual relatives whose discussions always led to the glory days of their aristocratic past. I grew up surrounded by joyful uncles and aunts—all of them impressively good looking. I’m amazed today that in my memories that miserable place comes as a place of joy and love. I remember the flowers that were planted all around. My grandmother was an extraordinary woman—she had lost three brothers in the war against the Nazis in Albania—she did everything possible to make life in the shack seem normal. What has remained with me is the extraordinary love that I was given in that shack. I also learned what resilience and human dignity mean. But I refused the rest: living with the glory of the past. I understood though that when people are denied a present and a future they take refuge in the past.

READ MORE…