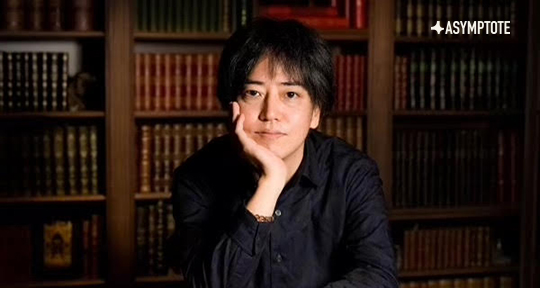

What does it mean to translate from the archive, especially when it is temporally and linguistically removed from the present? In the golden age of Philippine Binisayâ poetry from the 1900s to the 1940s, the virtuosic poet, critic, and priest Fernando A Buyser cemented his place in the canon of Philippine literature for both his nationalistic, romantic poems and his curating of indigenous oral poetry. In this intimate essay, Editor-at-Large Alton Melvar M Dapanas considers the sociohistorical, linguistic, and personal complexities of excavating the archive for the works of Buyser and rendering his poetry into English. Dapanas meditates over Buyser’s legacy in Philippine literature, as well as the joyous yet fraught process of unearthing texts from the antiquity.

The stories that comprise us have left us both wanting more, wishing we had access to a fuller narrative frame. I call this wishing-wanting desire “the ghost archive.” Everything we need to know but cannot know as we keep circling and sniffing around the edges. Everything that keeps affecting us and affecting others through us. Everything that remains right there, but just out of reach.

—Julietta Singh, No Archive Will Restore You

Scouring through the Stanford University Libraries’ press archives of early twentieth-century Philippines in the midst of the Delta variant surge brought me to Fernando Buyser y Aquino and the years between 1905 and 1937. I suppose, based on these archives, that Bishop Fernando A. Buyser was a typical Filipino priest: he officiated baptisms, headed processions during important religious holidays, performed administrative functions at the council of bishops, held committee membership for fundraisers, went to a lawyer for the church’s legal documents to be notarised, among other duties. Of the Aglipayan Church or the Philippine Independent Catholic Church, later renamed as Iglesia Filipina Independiente (IFI)—a religion that half of my family still practice to this day and the same church that baptised me (though I no longer identify as Christian)—Bishop Buyser preached to areas outside his diocese. In a 1934 gacetilla, or newsletter, published in the bilingual La revolucion [The Revolution], he held what seemed like religious missions to Iloilo and Negros Oriental and Occidental provinces, and the neighbouring Antique, Romblon, and Capiz, his diocese comprising Cebu, Bohol, Samar, and Leyte. In his early pre-bishop years as an ordained priest, he wasn’t spared from criticism. Drawing flak, a satirical piece and an editorial were published, calling him out in separate issues of the Catholic-owned periodical Ang camatuoran [The Truth]. What caused this, apparently, was Buyser’s Lutherian critique against the ways of the Roman Catholic clergy. Given the 1902 schism of the IFI from Rome, tensions were bound to arise.

All these seem typical given his stature and the times, and in many ways, at least based on the archives, he may have been. Except that he was also a poet and wrote short stories, plays, novelettes, pre-modern forms of ars poetica on both theoria and praxis, as well as literary and cultural criticism. In another periodical, Ang suga [The Light], a writer working under a penname, most likely a contemporary, would dedicate a poem to Buyser. A Philippine Magazine article, concerning a survey of ancient allegorical fables, published May 1936, cited him for expert opinion. Both are evidence that his peers looked up to him, offering a glimpse of the happenings inside the literary circles back in the day. In these same papers, he was congratulated for his prolific output, notably his works titled Ang Ulay sa mga Kasakit [The Virgin of Sorrows] and Ang Arka sa Kaluwasan [The Arc of Salvation]. (It was in his collection Ang Rueda ug ang Oraculo [The Wheel and the Oracle] where Buyser advertised his PO box, the very address of the IFI cathedral which still stands today in Mabini street of Cebu.) The last mention of him in the same archive was in 1937 from La revolucion, about his pre-retirement designation down south as parish priest of Mainit, Surigaw, now Surigao del Norte, in Mindanao where he died a few years later. A government-run school in Mainit’s adjacent municipality, Tubod, named after him (F. Buyser Elementary School) was built in 1961 and still runs today.

Craft-wise, what positioned him further in the canon is his anthologising and curating of oral poetry indigenous to the Cebuano Binisayâ-speaking Filipinos in the two volumes of Mga Awit sa Kabukiran [Mountain Songs], first published by Liberty Press in 1911 and republished as a second edition in 1924. Dedicated to his “yutang-natawohan” (Motherland), Mountain Songs collated various poetic forms such as balitaw (a song and dance love debate between a man and a woman), harito (shaman’s prayers), kulilisi (improvised recited verse, sometimes spelled as kolilisi), awit and saluma (poetic songs), garay (informal poetry), and balak (formal poetry). The act of collating oral Binisayâ poetic forms, something rarely done at the time (unless you’re a white anthropologist-missionary who married a Filipino woman), was a “pioneering work [that] proved to be the best grounding in the poetic tradition in the Visayas,” in the words of poet and translator Marjorie Evasco. Even American ethnologist Donn V. Hart tried to locate Buyser’s collection of 360 riddles, Usa Ka Gabiing Pilipinhon [A Filipino Night], for his critical study on folktales although to no avail.

READ MORE…