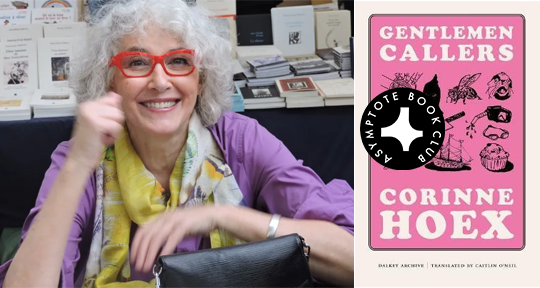

In the world of letters, sex is too often strangled with extremes. Whether entrenched in symbolism, proliferate with diverse politics, or avoided altogether, this pervasive element of human experience is too often deprived of its more irreverent, mirthful, and pleasurable evocations. In our Book Club selection for April, award-winning Belgian writer Corinne Hoex presents a series of sexual dreams and fantasies in Gentlemen Callers, a collection that astounds, subverts, and engages with physical pleasure in joy, levity, and dreaminess. Unabashedly funny and fiercely sensual, Hoex’s journey through the erotic is a breathless delight.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Gentlemen Callers by Corinne Hoex, translated from the French by Caitlin O’Neil, Dalkey Archive Press, 2022

Literature has—particularly in the last century or so—become a Serious Business. I’m not speaking here of economics or occupations, but rather the affect of seriousness. Very often, the more tragical, gritty, and dark a tale is, the more lauded its reception becomes. For whatever reason, we have decided that comedy is not as worthy of critical attention or canonization, in spite of the fact that, in my estimation at least, comedy is infinitely harder to pull off. Humor is culturally specific, temporally tied, and situationally contextual, and all of these facets are amplified in the context of translation, where puns and plays become tangled in tongues. This is what makes Gentlemen Callers, by Corinne Hoex, translated from the French by Caitlin O’Neil, a truly astonishing outlier. While French literature enjoys a fairly prolific publication rate in English, the kinds of literature chosen for publication are often cerebral, philosophical, and introspective. Hoex’s series of vignettes, too, are interiorized, in that they are dreamworlds, but they are also fleshy, sensuous, and gilded with a teasing tone firmly rooted (pun intended) in sexual exploration and fulfillment.

Gentlemen Callers is somewhere between a novel and a short story collection; a first-person narrator delivers each brief tale, and her power to call men (and other more fantastical lovers) into her dreams perennially returns, but nearly every chapter is self-contained, and the narrator shapeshifts as she sees fit, all the better to become the tool with which her lovers might exercise their expertise. Each vignette is titled after an occupation, some of which happily gesture to the realm of tried and true pornographic tropes (like The Mailman or The Schoolteacher) while others are more oblique: The Butcher, The Furrier, The Beekeeper. Following each chapter title comes an epigraph, all taken from some of Europe’s most famous canonical authors: Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, Émile Zola. As one might expect, all the referenced authors are men, and all the epigraphs gesture to the occupation under examination, albeit some more obliquely than others. The narratorial play here is not only to reference the heights of physical joy one can achieve with a skilled workman, but also to reference the heights of intellectual joy one can achieve when toying with the phantom canon, with the master’s ghost.

Take, for example, the epigraph from “The Young Priest 2,” one of only three vignette continuations in the book. It’s from Thomas à Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ, perhaps one of the most widely read Christian works after the Bible itself. The quote: “How pleasant and sweet to behold brethren fervent and devout, well-mannered and disciplined!” This earnest, chaste sentiment takes on a new and sensually playful valence when paired with the priest’s vignettes, in which a handsome man of the cloth visits the narrator in her dreams and delivers an intercession upon which, “the Holy Spirit enters me. God clasps me in His arms, possesses me with His mouth, radiates His light by waking the wild urges of his servant’s potent sap.” No doubt Kemis himself, who in his teachings stressed silence, solitude, resisting temptation, and purging fleshly pleasures, would be outraged at the implication that actions “fervent and devout” might be found in the narrator’s oblique allusion to fellatio, “kneel[ing] on [her] white cloud, back arched, face upturned, lips parted, surrendering [her] flesh to the Redeemer.” READ MORE…