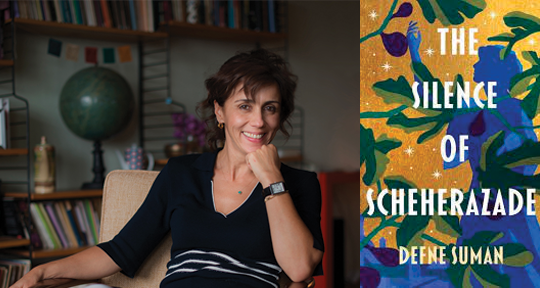

The Silence of Scheherazade by Defne Suman, translated from the Turkish by Betsy Göksel, Head of Zeus, 2021

In the unfathomable numbers of our current reality, big players—political, economic, scientific—very often overshadow everyday mundanities, the smallness of ordinary people’s lives. In this case, smallness is not meant as an insult, but rather as an important facet that we all lose track of when inundated with the major headlines numbering pandemic casualties. Similarly, the lives of the many characters in Defne Suman’s epic and entangled The Silence of Scheherazade are also eventually dwarfed by the backdrop that consumes them—the fallout of World War I and the crumbling Ottoman Empire.

Part Victorian Gothic, part cosmopolitan modernist, and part metatextual experiment, The Silence of Scheherazade traces the lives of a massive cast of characters from the late 1800s to the early 2000s. Jumping across decades and points of view with ease, moving forward and backward in time, the novel weaves a tangled tapestry over the city of Smyrna. Scheherazade sometimes narrates her life in the first person, but more often draws on the ghosts of the past to let other players come forward and speak. “My birth,” the novel opens, “on a sweet, orange-tinted evening, coincided with the arrival of Avinash Pillai in Smyrna.” A few pages later, Scheherazade recedes and we shift to Pillai himself, with his first encounter of a new home. “The young Indian man, fed up with the smell of coal and cold iron which had permeated the days-long sea voyage, was inhaling the pleasant aroma of flowers and grass. Rose, lemon, magnolia, jasmine and deep down a touch of amber.” In and out Scheherazade leads us, from the Armenian quarter of the city to British spies in the consulate, from wealthier Levantine suburbs to humble Greek grocers.

The focus falls especially to the women of this world, women who are constrained by all those huge players above them to live their lives in accordance with the expectations of their classes, their religions, their families, their countries, and who are forced to extraordinary measures when they fail to comply. Whether the flighty Juliette, the willful Edith, the skillful Meline, the daydreaming Panagiota, or the madwoman Sumbul, each woman is faced with terrible personal tragedies which are locked away behind walls of claustrophobic cultural silences. Edith, for her part, becomes addicted to hashish in order to endure the agony of each day. “That day had come around again. No matter how much hashish she smoked or how many secret ingredients Gypsy Yasemin added to it, whenever this date came around, that long-ago memory returned, like the sun shining through fog.” Panagiota, undergoing a different struggle, agrees to a distasteful marriage in order to protect her family.

[She] had not mentioned the fear that was eating away at her to her mother and father. They would have been alarmed that she’d been taken in by the words of an Indian man she’d met on the street, and they wouldn’t have taken her concerns seriously anyway. If she’d brought up what Avinash Pillai had said at supper, for example, her father would have shouted angrily, “For God’s sake, that’s crazy nonsense!”

In a world where she’s unable to voice her fears or her knowledge, Panagiota’s only recourse is to avail her Greek suitor, who has the power to rescue not only her but her whole family from the encroaching violence.

Perhaps the most important character of all, however, is Smyrna itself. A port city at the crossroads of multiple intersecting languages, cultures, religions, and countries, Suman deftly paints a picture of a city which endures occupation after occupation, a quiescent powder keg inching closer and closer to the flame with each influx of new political superpowers. Yet through all the grim shadows of war, violent modernization, and conquest which dance across the pages, Suman’s tale is at its heart about those small people living their daily lives within the city, loving each other and the land beneath them. Grocer Akis tells the local Greek boys:

Don’t get tricked by this Greater Greece game; don’t get yourselves into trouble. Big guys play their games, but they always choose young men like you as pawns. You live in the most beautiful city in the world, one of your hands in butter, the other in honey. Does it matter who rules us? Do you think we’d see this abundance if we were foisted off on Greece? If you don’t believe me, go to Athens. Go and see if there’s one single part of it that can compare to our bountiful Smyrna.

The characters love Smyrna in all its jumbled glory, and even in the midst of total destruction, there are hints and moments of beauty—as well as the knowledge that it’s very difficult to quash something which has survived for thousands of years. “Do you know what I think?” asks the young woman Ipek to Scheherazade. “You can’t kill the spirit of this city, no matter what you do. You can set it on fire, tear it down, evict all of its people and import others in their place, but that love of freedom, that vivacity will always resurface.”

Göksel handles the translation of this complex tale just as skillfully as Suman herself weaves it. As one might expect, the intermingling of many cultures leads to the intermingling of many languages. Scheherazade herself narrates her tale, so we’re told, in Greek, Arabic, French, and the Romanized Turkish (a transition which took place during her lifetime). Göksel sprinkles in just enough of the original languages to remind readers of the cultural backgrounds of the various characters, but not so much that reading becomes a chore. Here’s an example from Akis’ wife, Katina. “Your neck and face are bright red. We’ll get Fotini to prepare some cream for you. Ah, paidi mou, my child! You’re a big girl, vre, but your head is still in the clouds.” In a different section, the wealthy Levantine Juliette to all her socialite friends, “Dear Anna is expecting another enfant—yes, don’t even ask! Twins this time! Mon Dieu!” The genius in Göksel’s deployment comes through when one realizes that, in Katina’s context, it’s very clear that the Greek is a part of her everyday speech, while in Juliette’s context it’s clear that the French is an affectation denoting her wealth. (In other parts of the book, she uses Greek much more naturally.) While these linguistic markers may very well be in the Turkish original, the question of whether to retain them in English and how to mark them—if it all—is often a vexing one for the translator, especially in a novel like this one that uses so many languages as part of its backdrop. Göksel manages to straddle the lines of taste, maintaining atmosphere without allowing the languages to become tokenistic or overbearing.

The Silence of Scheherazade is a daunting novel, and the process of reading it is sometimes confusing, sometimes infuriating. Just as you become invested in one character, you move to another, unsure of your place in time or your connection to what came before. This discursion, however, is fitting for a novel that seeks to explore personal traumas across generations in times of war, occupation, and conquest. And like Scheherazade herself, the hope of endurance, the hope of survival, the hope of telling one’s own story, outshine and persevere through the manifold struggles—the underlying human pulse beneath the events of time.

Laurel Taylor is a PhD candidate in Japanese and Comparative Literature at the Washington University in St. Louis. Her dissertation focuses on the formation of online literary communities and online literary production, and to that end she has received a Fulbright to conduct research in Japan for the next year. Her translations and writings have appeared in The Offing, the Asia Literary Review, EnglishPEN Presents, Transference, and Mentor & Muse.

*****

Read more on the Aymptote blog:

- Literature as Homeland: The English-Language Debut of Tezer Özlü

- A Brief Introduction to Nermin Yɪldɪrɪm’s Secret Dreams in Istanbul

- Turkish Dude Lit Has a “Dad Rock” Moment: Barış Bıçakçı’s The Mosquito Bite Author