Carl de Souza began writing Kaya Days in the tumultuous throes of the very event it depicts—the 1999 riots in the East African island of Mauritius, following the death of popular singer Kaya. From the description of those frenzied days comes a work that renders the electric immediacy of sensation with vividness, kinetics, and a musician’s aptness for rhythm. We are proud to announce this singular work as our Book Club selection for the month of September—a formidable voice in Mauritian literature and an unforgettable novel of revolution, poetry, and becoming.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

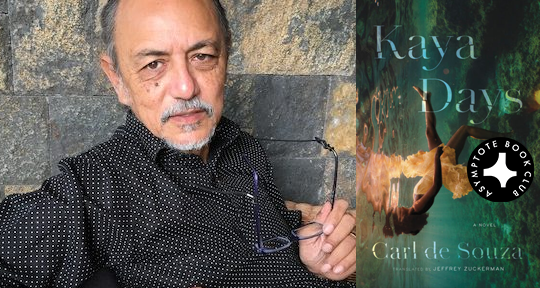

Kaya Days by Carl de Souza, translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman, Two Lines Press, 2021

If war is a matter of hurry up and wait, then the rest of life is often the opposite. As Hemingway says, “Gradually, then suddenly.” So it is with Santee Bissoonlall and her mystical journey in Carl de Souza’s Kaya Days, translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman—“. . . all this had happened gradually, with the quiet of a new beginning.” For many years, Santee is a child. Then suddenly, over the course of a violent and chaotic few days, she is a woman, a queen, a figure receding. De Souza’s intricate novel propels her on the journey of becoming, as she traverses the tumultuous 1999 Mauritian riots.

The riots were an uprising of Mauritian Creoles following the death of Joseph Réginald Topize—better known by his stage name, Kaya—in police custody under suspect circumstances. The word kaya is a reference to Bob Marley’s 1978 album of the same name, and Kaya, as a musician, was a pivotal figure in the blending of Mauritian sega and reggae into a genre that would come to be known as seggae. He was also an activist for Creole rights and the decriminalization of marijuana, among other things. Yet this political-historical thread is not the primary melody of de Souza’s novel; rather, it serves as the thrumming pedal note to Santee’s journey through the burning streets.

We follow her as she quests for her lost brother, Ramesh—younger than her yet seemingly so much worldlier, as he has been permitted to attend school and traverse the outside world, while Santee has been kept at home, condemned to household drudgery by her sex and her family’s poverty. For Santee, the confusion of the riots is a distant rumble; it is the more immediate problem of a missing sibling which drives her on through the ruined streets.

It was getting dark under the mango trees. She had no hope of understanding, but that wasn’t what she needed to do, that wasn’t her job, she was just here because Ma couldn’t be. What she needed to do was find Ram; one of these alleys would lead to him, but which one?

Around her, Santee hears the gossip of the streets, the rumors of Kaya’s brutal end, the voices singing his songs, the anger being drawn upon ethnic lines, but indeed she does not understand, and seeks only the places familiar to her brother yet strange to her. In the above excerpt, Santee has no clear object of understanding, but perhaps there is no object precisely because of her unknowing. Her object remains instead a brother just out of reach, a taunting ghost who answers only to their mother and never to her. From backroom brothel to midnight graveyard, from rambling taxi cab to looted upscale ruins, and from a veritable Eden to the depths of the drought-stricken river running through the gorge, Santee seeks like Orpheus for Eurydice, observing the ruins, yet dwelling more often on the injustices forced upon her as she attempts—and often fails—to navigate the unfamiliar world of men.

Santee’s lack of understanding and worldliness, however, does not mean that she is completely naïve to the injustices of the world. She understands, for instance, that she cannot run through a Creole neighborhood shouting “Ramesh” with her Hindu accent, lest she attract the attention of the rioters and earn their ire. She understands that she’s been short shrifted by her mother’s valuing of Ramesh over her. She understands that injuring the weak is not amusing and it is not a sign of strength.

[Milanac] hefted a jar of preserves but caught himself and gave it to Santee instead. Go for it—what’s your name? Shakuntala. Well, Shakuntala, be my guest. Go on! Throw it! You just going to stand there all day staring at me like that? You want those shoes or whatever? The first throw at the thick glass was awkward—the jar bounced back, barely missing her, and Milanac laughed heartily. [. . .] Go for it, Shakuntala, have at it! Fury rose up in her and she grabbed the jar and threw it with all the anger she had at Milanac, at the blister on her foot, at Ram, who threw stones at dogs while she had to clap whenever he hit his target amid the din of animals barking in pain and fear—she threw the jar against the glass.

De Souza’s densely packed novel is a disorienting one, purposefully so. He jars his readers again and again through sudden shifts in character narration, transmogrifying objects and people, and juxtapositions of violence and jubilation. From the above excerpt, readers can gather that dialogue blends into prose with no warning, no marked punctuation, and no paragraph break. The words tumble, churn, and burn like the refuse on the streets after the riots.

Identity is a fluid thing in this confusing labyrinth, as Santee is transformed first into a prostitute, then Shakuntala, a mythohistorical queen from the Mahabharata questing for the husband cursed to forget her. Other characters too become fluid ideas bound by larger-than-life names—Ram, ghostly though he is, becomes Rambo, Ramon, Ramses. One of Santee’s guides bears a tattoo of the name and team Ronaldo Milan AC—a reference to the famous footballer—yet the reference flies over Santee’s head; she dubs him Milanac instead, pulling him into her tenuous world and molding him into her anchor, the last touchstone before “gradually” becomes “suddenly,” and the days of the riots collapse in a haze, into the Big Bang of Shakuntala’s universe.

—these were empty days, days without memory, and, every morning, everything started all over again on a different track.

. . . these were new days, days full of promise.

. . . those were days with no yesterday, days with no tomorrow, and there was no telling who took the other.

The very indefinability of the violence of this book collapses time, collapses meaning, collapses self.

Translating such a dense book is no easy feat, but Zuckerman handles it admirably, allowing the sprawl of de Souza’s prose to linger and spill where other translators might be tempted to neaten or punctuate. At the same time, though, to balance the opacity of the prose, Zuckerman has also made a conscious effort to eschew language that could justifiably be translated into something more grandiose. Take, for instance, the above phrase: “. . . those were days with no yesterday, days with no tomorrow.” The French—”c’était des jours sans histoire et sans lendemain”—could just as easily be translated into “those were days with no history and no future,” but such a translation would shift the reader from Santee’s melody to the pedal note which undergirds her tale, consciously shifting from a personal narrative of becoming to an overt sociopolitical commentary.

Zuckerman also allows moments that resist translation to stand in their resistance, a fitting rhetorical move given the ambiguity of Marley’s kaya and all that it could possibly represent. Santee hears Marley over a taxi radio, repeating his refrain “I got to have kaya now, got to have kaya now”—but the meaning of kaya is never entirely clear, and indeed in the shadow of the riots, it is meant to be multivalent. Kaya refers, of course, to Kaya the singer, but it also refers back to Marley’s music and rhythm, as it also refers to marijuana, yet at the same time kaya is a concept Marley refused to define: “You have to play it and get your own inspiration. For every song have a different meaning to a man.” In just the same way, the kaya days are new days and empty days and days of promise. It is up to the reader to sit in that ambiguity, to sit in the roiling transformations Santee experiences and observes, and if they refuse to flow with the tides, to be left behind.

Laurel Taylor is a PhD candidate in Japanese and comparative literature at Washington University in St. Louis. Her dissertation focuses on the formation of online literary communities and online literary production, and to that end she has received a Fulbright to conduct research in Japan for the next year. Her translations and writings have appeared in The Offing, the Asia Literary Review, EnglishPEN Presents, Transference, and Mentor & Muse.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Announcing Our August Book Club Selection: After the Sun by Jonas Eika

- Announcing Our July Book Club Selection: The Animal Days by Keila Vall de la Ville

- Announcing Our June Book Club Selection: FEM by Magda Cârneci