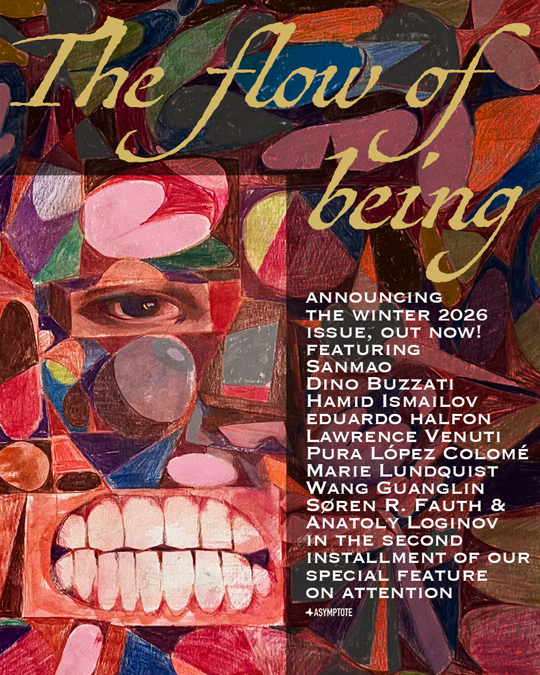

As authoritarianism continues to take hold across the world, writers and translators are compelled to revisit an age-old question: What might art offer in response? Perhaps not answers, but something quieter and more resilient—a reminder of shared human frailty, and of the possibility that our “flow of being,” as Anatoly Loginov writes, might arrive at a “narrow neck” where attention itself becomes an existential force. Writing in our Winter 2026 Issue, which also marks Asymptote’s fifteenth(!) anniversary, Loginov turns to a literary and philosophical tradition that seeks “not mastery over an object, but communion with it, even if that communion burns.” For this second of our two issues devoted to attention, we bring together his tour de force survey of 200 years of Russian thought with a luminous travelogue by the beloved Taiwanese writer Sanmao, an excerpt from Guatemalan author Eduardo Halfon’s prizewinning Tarantula, an exclusive interview with Uzbek novelist Hamid Ismailov, a quietly devastating story by Italian master Dino Buzzati, and new translations of Milo De Angelis by Lawrence Venuti, alongside never-before-published work from 32 countries. All of it is illustrated by our talented Dublin-based guest artist Yosef Phelan.

If Loginov argues that attention, when cultivated deeply, can ground compassion toward others, Finnish playwright Minna Canth takes this ethical impulse further into the realm of collective action. In her barnburner drama, railway workers pushed beyond endurance channel their shared anger into defiant sabotage, making exploitation visible at last. Writing from a different frontline, Kurdish journalist Zekine Türkeri bears witness to life in the Mahmur refugee camp in the days preceding an ISIS attack, showing how attention to the living entails the inescapable labor of mourning the dead. Elsewhere, in Egyptian writer Mariam Abd Elaziz’s fiction, characters struggle to care for one another as they swim and sink in the deadly currents of maritime refugee smuggling. The issue’s arc closes with an interview in which China’s Wang Guanglin reflects on the difficulty of imagining a genuinely global literature at a moment marked by isolationism, xenophobia, and resurgent nationalism. World literature, he suggests, remains, at heart, a problem of attention: of who is seen, who is heard, and who is permitted to remain invisible.

For fifteen years, Asymptote has been organized around this problem. Founded on the conviction that literature across languages deserves sustained, serious attention, we have worked to widen the field of vision—introducing readers to voices beyond dominant centers, and treating translation not as a secondary act but as an ethical and imaginative practice in its own right. If this project has mattered to you—if you believe that attention, patiently given, can still resist the forces that would narrow our view—we ask you to help keep it alive by becoming a sustaining or masthead member. Your support ensures that the flow of being we trace here continues to move, freely and exuberantly, into the years ahead.