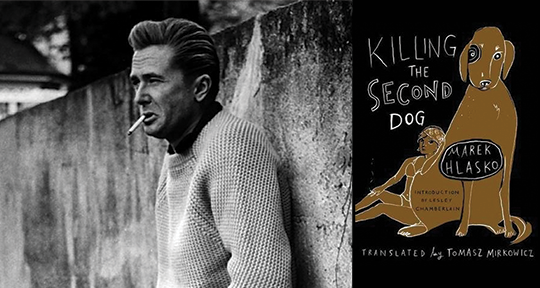

Killing the Dog by Marek Hłasko, translated from the Polish by Tomasz Mirkowicz, New Vessel Press, 2014

Marek Hłasko’s novel, Killing the Second Dog, is set in Tel Aviv, but it isn’t any Tel Aviv that I know. Not only the years that separate my Israel (I was born there in 1982) from the novel’s newly independent Israel of the early 1950s account for this lack of familiarity. Nor is it the fact that Killing the Second Dog is, essentially, a crime novel. Hłasko’s Tel Aviv is an identity-less city, where a multitude of languages is spoken and a variety of currencies is exchanged. Still overcoming British rule and catering to the many post-war tourists financing its new path, this Israel offers itself up for grabs, trying, in spite of the suffocating heat and the shoddy infrastructure, to constitute as small an interruption as possible.

The central feeling of estrangement, however, the gnawing discomfort I felt as I read this book, came from the fact that my Tel Aviv, and especially the beach, where the bulk of the novel is set, is nothing if not laid-back. Traffic jams, bad parking, sweltering heat—they all fade into the feeling of a constant vacation, of beers on rickety wooden tables and sooty flip-flop-clad feet.

Hłasko, on the other hand, presents readers with a Tel Aviv that is constructed from bricks of anxiety. In a town cursed by the dry desert wind, Hłasko’s protagonists, Jacob and Robert, are surrounded by lowlifes, criminals and lost souls. Their Israel is one of jail time, seedy hotels, dirty deals and sweaty beds. Jacob is constantly looking for something of his own, but everything he ever has—the dog, his room, a towel—must be shared with another.

The plot is simple. Two Eastern European nobodies are romance con artists. Robert, a former theatre director who believes plays were meant to be performed in real life rather than on stage, writes lines for Jacob, the good-looking one, and with the help of a charming dog (which must be replaced with each iteration of their scheme), they trick rich American tourists into falling in love with Jacob and paying his fictitious debts off so that he may join them in the United States. The money is pocketed, the relationship falls through, on to the next victim.

But the script Robert had come up with is so inventively ridiculous that it creates a circus of sorts on the beachfront: Jacob is to play an angry, miserable and belligerent man in order to win the love of kindly women. In a fit of rage, realizing that he would never be able to join his beloved in America and wanting to hurt her and himself, making him appear cruel and heartless in her eyes, he must shoot the dog, his only possession, and then attempt suicide by swallowing sleeping pills. This is no fraud—the dog is now dead, and on at least one occasion Jacob alludes to, the forged suicide attempt had almost culminated in very real death.

And the most ludicrous part is, by Jacob’s own testimony, the two don’t ever do much with the money they swindle out of the women. Most of it pays for the dog’s food, and the rest is spent on cheap movies and cigarettes. While Jacob laments not having been born rich, while he is plagued with guilt for his lowly way of life and refuses to talk about one of his victims, who, after being admitted to a mental health institution, had killed herself over his betrayal, he never attempts to change his situation. He mentions previous occupations, all leading him in some way or another to serve time in prison. He enjoys conning his own partner, and has no interest whatsoever in finding real love. He is an aspiring actor who hates acting and an aspiring writer who won’t write. He dreams of a room of his own to disappear into with his books. But he, and all the other characters in Killing the Second Dog, know only how to dream, incapable of making their dreams come true. Whenever he stumbles upon a chance for real emotion and true bravery, he makes sure to squash it as best he can. In the book’s touching final scene, Jacob makes a weak attempt to take over the role of director of his own life, but it’s just another meaningless scene in the fiction of his life. In many ways, he is the second dog that must be sacrificed for the show to go on.

Unkempt, unwashed, unpleasant and unethical, Jacob and Robert appear not as the Big Bad Wolves of Tel Aviv. Instead, they read like two empty shells conjuring up the remains of their strength, whatever was left of them after communism and World War II had its way with them back in the home country. We learn little of their personal histories, but enough to know they have been traumatized in ways that, left untreated, lead men to nothing but more violence, more hate. In their pathetic aggressiveness, they manage to overcome readers’ distaste for them and become almost sympathetic.

This feat is greatly thanks to Hłasko’s talent of blending the old with the new in practically imperceptible ways. Bringing up small anecdotes from his characters’ past (“I didn’t learn anything in school. I misbehaved so badly they used to make me stand in a corner with my face to the wall. That was my punishment. You have to admit that under those circumstances I didn’t stand a chance of learning anything. Even the gym teacher would throw me out the door,” “My real father was a good and gentle man who died when I was six”), he accentuates just how empty their present is—their future, most likely, nonexistent. His cool, staccato style is held back for moments when one of the characters lets slip a sentimental run-on statement, puncturing a reader’s seemingly already-made-up mind.

Tomasz Mirkowicz has created a translation simultaneously exotic and familiar, resulting in a sense of pleasant disorientation. Without explaining too much about the time and place, avoiding the temptation toward footnotes, he serves English readers the colloquial style of dialogue and narrative in an easy, palatable and familiar way, only to then surprise them with a punch of that delightful strangeness, which is often the most pleasurable part of reading translated work. This is a novel that will haunt me, like a dog.

***

Yardenne Greenspan, Asymptote editor-at-large for Israel, has an MFA in Fiction and Translation from Columbia University. In 2011 she received the American Literary Translators’ Association Fellowship. Her translation of Some Day, by Shemi Zarhin, was chosen for World Literature Today’s 2013 list of notable translations. Yardenne’s translations include work by Rana Werbin, Gon Ben Ari, Nahum Werbin, Vered Schnabel, Kobi Ovadia, Yirmi Pinkus, Ron Dahan, Alex Epstein and Yaakov Shabtai. Her fiction, essays and translations have been published in Hot Metal Bridge, Two Lines, Words Without Borders, Necessary Fiction, Agave, World Literature Today, Shelf Unbound and Asymptote, among other publications. She is currently working on her first novel.