Of all that Mahmoud Darwish has left to us in his legacy of prismatic language, transcendent humanism, and elucidation of Palestinian consciousness, the greatest gift might be his belief that literature can confront any question—even those that seem most unanswerable—and consequently, his profound demonstration of living, gracefully and with dignity, inside ambiguity. Translated beautifully by Catherine Cobham, A River Dies of Thirst is the final book of poems published in Darwish’s lifetime, and it provides us with another opportunity to share reality with a writer who has always astonishingly made poetry the site of actuality—the poem as a place where thinking is forged. They precisely mark enormous emotional ranges with a single, pointed image; they make short lines of long wars; and they push us, as always, towards the seeking of meaning. In the final lines of his memoir, Memory for Forgetfulness, the poet repeats: “No one understands anyone. / And no one understands anyone. / No one understands.” Perhaps so. But as these poems congregate irresolution with desire, the ethereal with the material, and conviction with inquiry—we get the feeling that we might begin.

A common enemy

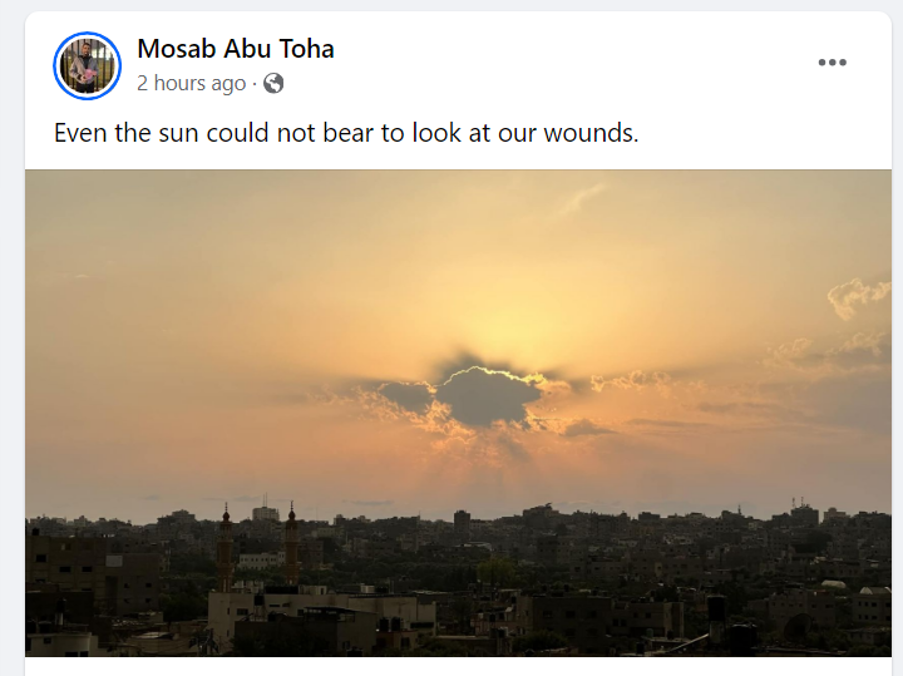

It is time for the war to have a siesta. The fighters go to their girlfriends, tired and afraid their words will be misinterpreted: ‘We won because we did not die, and our enemies won because they did not die.’ For defeat is a forlorn expression. But the individual fighter is not a soldier in the presence of the one he loves: ‘If your eyes hadn’t been aimed at my heart the bullet would have penetrated it!’ Or: ‘If I hadn’t been so eager to avoid being killed, I wouldn’t have killed anyone!’ Or: ‘I was afraid for you if I died, so I survived to put your mind at rest.’ Or: ‘Heroism is a word we only use at the graveside.’ Or: ‘In battle I did not think of victory but of being safe, and of the freckles on your back.’ Or: ‘How little difference there is between safety and peace and the room where you sleep.’ Or: ‘When I was thirsty I asked my enemy for water and he didn’t hear me, so I spoke your name and my thirst was quenched.’ Fighters on both sides say similar things in the presence of the ones they love. But the casualties on both sides don’t realise until it’s too late that they have a common enemy: death. So what does that mean? READ MORE…