As Mekhitar Garabedian told Eva Heisler, Asymptote’s former Visual Editor, “[b]ecause of the contemporary political, economic, and cultural situation of Lebanon and Syria, and of the Middle East in general, these places (and their histories) are meaningful, significant, and vital presences in my daily life. Diaspora means experiencing a disseminated, shattered, divided self.” This statement suggests that diasporic identity is both a geographic and historical condition and that it is marked by both continuous felt presence and continuous literal absence. It is, in this way, a condition of both the shattering Garabedian names and one of possibility, as demonstrated in the art that comes from so many diasporas, including Garabedian’s own. In this edition of our recurring series highlighting visual work from our archives, we revisit Garabedian’s feature from our July 2015 issue.

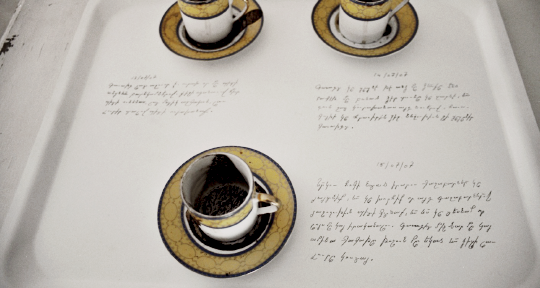

Without even leaving, we are already no longer there, 2010–2011, video installation, DVD, 3 screens, dimensions variable, 3 x 30min. Detail. With Nora Karaguezian and Laurice Karaguezian.

Cinematography by Céline Butaye and Mekhitar Garabedian.

In my research, I contemplate the conceptual possibilities of the work of art. I often use modes of repetition that reference literature, philosophy, cinema, pop culture, and the works of other visual artists—citing, replicating, and distorting references, exemplary modes, and works from art history and from my own history. I employ references as structures or elements upon which I can build, adding different layers, or contaminating them with altogether different contexts.

My interest in citation developed instinctively, probably through the experience of growing up with two languages, which engendered the feeling of always speaking with the words of others, perhaps also by encountering the early films, full of citations, of Jean-Luc Godard, at a young age, and through growing up in the nineties with the art of sampling as practiced in hip hop culture.

My use of citations or references also comes from my interest in the idea that identity is always a borrowed identity. One can never pretend to be someone out of the chain of the past. One is always speaking with the words of others. Talking with the words of others requires a library (and a dictionary) of the words of others. In my work, I use talking with the words of others and the construction of a (personal) library as a conceptual artistic strategy. My use of modes of repetition also relates to the Catastrophe; after a disaster, only thinking in ruins, in fragments, cut-outs or debris, remains possible. READ MORE…