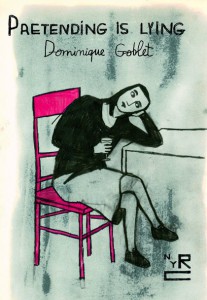

Pretending is Lying by Dominique Goblet, tr. Sophie Yanow, New York Review Books

Review: Sam Carter, Assistant Managing Editor

Dominique Goblet’s Pretending is Lying, translated by fellow cartoonist Sophie Yanow in collaboration with the author, immediately recalls the best work of those figures like Alison Bechdel, Adrian Tomine, and Chris Ware, who have done so much to insist on both the relevance and elegance of the graphic narrative form in the Anglophone world. Fortunately, New York Review Books is dedicated to showcasing the many voices contributing to an ongoing, worldwide comic conversation, and its latest contribution is this Belgian memoir. Originally titled Faire semblant c’est mentir, it centers on the experiences of Dominique—a fictionalized version of the author herself—as she navigates fraught relationships with her parents, including with her looming lush of a father. Also sketched out is a romantic relationship where Dominique attempts to grapple with that most fundamental question of heartbreak: why did he leave me?

A certified electrician and plumber, Goblet clearly understands a thing or two about the necessary connections running through structures to make them work, and her illustrations carry this skill into Pretending is Lying, her first work to appear in English. Image and text perform an intricate choreography, reveling in an aesthetic that frequently slips between the easily imitated and the utterly remarkable. If the easy analogy for reading comics is the process of examining a series of film stills—and even if we might be tempted to label parts of the construction of this work cinematic—I would instead suggest that Goblet offers something that more closely resembles a well curated series of photographs, each of which could easily stand on its own, given each frame’s clarity of vision and attention to detail.

In illustrations that move from Rothko-like explorations of pure color to nuanced collections of penmanship that gradually reveal a series of ethereal forms, the melancholia that we often find in other works emerges here as well—maybe there’s something about the form that lends itself well to expressions of such emotions in its ability to match words with alternatively visceral and measured strokes. The muted color palette of Pretending is Lying is also remarkably expressive. READ MORE…